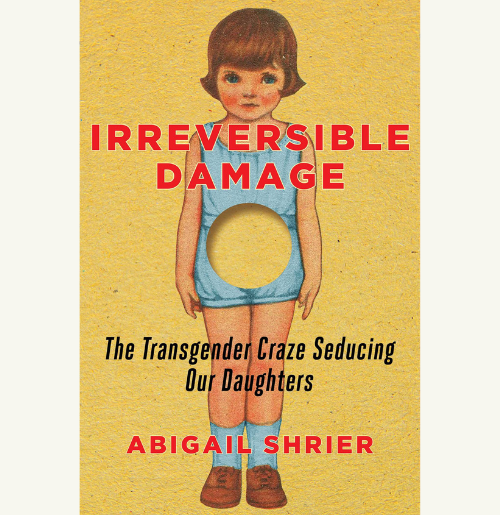

The transgender movement can be hard to take seriously. It is so bizarre that one would like to believe it is confined to the cerebral sphere of politically correct professors and the garrulous spouting of media gurus. Unfortunately, it is an expanding movement that is misleading more and more people. Two recent books, Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters by journalist Abigail Shrier and Transcending Gender Ideology by philosophy professor Antonio Malo, are helpful in explaining how individuals can become so confused about their identities that they come to believe they are a man in a woman’s body or vice versa.

Abigail Schrier’s book is written for a popular audience, especially for the parents of teenage girls. It documents the many “authorities” in our culture that are encouraging young women to think they can become happier by changing their sexual identity. It is an excellent resource for discovering how identity confusion is being spread in the United States and how to defend one’s children against it. Professor Malo’s book is a much more difficult read. It is intended for the philosopher or philosophically inclined. It shows the deeper roots of the transgender movement in Marxism and radical feminism. More importantly, it investigates the reason for human vulnerability in the delicate task of developing a mature sexual identity and defends natural sexual difference and heterosexual marriage using the concepts of generativity and gift.

The more accessible of the two, Shrier’s account of the transgender dysphoria epidemic afflicting teenage girls in the First World is chilling. As my youngest daughter is happily dating a young man and finishing college next year, I did not expect to be as deeply disturbed as I was by this excellent book. But I also have twelve grandchildren to worry about, and my compassion for all adolescents grew as I read the story of the battle for their psyche. Shrier presents a convincing case that the epidemic is spread through “peer contagion” and media propaganda. Transition gurus online, schools, therapists, doctors, and surgeons are all complicit in pushing girls into taking powerful hormonal drugs and undergoing disfiguring surgeries. These drugs often lead to sterility and increase the danger of cancer, and both kinds of treatments have led to an increase in depression and suicide.

The psychic alienation experienced by “transitioning” girls is also a flight from woman, born of the same fallacies that gave rise to the sexual revolution and radical feminism alike.

Parents need to be warned of the assault their daughters will almost certainly encounter in our very broken culture. They also need to know that their authority is being systematically undermined by the very people who are supposed to help them take care of their children. Shrier conducted 200 interviews and collected an impressive array of statistics to prove her thesis that, in the last ten years, most of the adolescent girls claiming to be “transgender” are simply unhappy girls who are struggling with social anxiety and discover from social media and their schools that claiming to be “trans” is an immediate way to get lots of “friends” online and lots of affirmation at school. Historically, Shrier points out, adolescents with gender dysphoria have comprised only .01% of the population and their ranks consisted almost entirely of boys who displayed some dysphoria since before they were two. Now, with the advent of social media, which wields a particular influence over teen girls, we are witnessing an explosion in gender dysphoria among adolescent females.

Shrier not only exposes the aggressive effort to push the transgender agenda on young women; she also formulates seven rules for parents to help their daughters avoid this contagion and how to fight it if it has already infected one’s daughter. Here are three of them.

The first rule is also the hardest: “Don’t Get Your Kid a Smartphone.” Since the introduction of the iPhone in 2007, anxiety, depression, anorexia, cutting, and transgender dysphoria have increased enormously among teenagers. In Britain, for instance, adolescents claiming gender dysphoria has increased 4000% in the ten years from 2007‒2017; the increase in the United States is 1000%. Teens are spending less time physically together than ever (especially after COVID restrictions); their principal social life is lived on their phone. A recent nationwide survey showed that the average American teenager spends nine hours a day on the phone! According to Shrier, then, it follows that being “friended” or “unfriended” on social media is becoming the most important thing in a teenager’s life.

But how in the world can you refuse your teens a smart phone, especially if they buy it for themselves? As I look at young couples I know, I see that many of them find it necessary to join or build a community of families that agree on raising their children according to certain standards. If all the parents agree that their children will not have smart phones, then flip phones can be a badge of belonging. Schrier also mentions that it is essential to organize physical get-togethers so that children and teens can have real friends with whom they do fun things in person. If girls were already pulled in by the transgender vortex, she found that decisive parental action was crucial in wresting their daughters from it. Sacrificing their own security, these parents often moved the family to a completely new environment and, importantly, disconnected the entire household from social media.

Two more of the rules Shrier suggests go together: “Stop Pathologizing Girlhood” and “Don’t Be Afraid to Admit: It’s Wonderful to Be a Girl.” Girls are not defective boys; they have their own gifts, including empathy and relationship-building. Women should stop envying men and stop thinking that the only way to be successful is to have a fast-track career and climb the corporate ladder to upper management and big money. Women can choose any career they wish now, but motherhood is also a beautiful vocation, even though it is so scorned by many in our culture. “We treat stay-at-home moms as the most contemptible of life’s losers. (I should know: I was one for years.),” Shrier recalls. When the distinctive value of womanhood, maternity, and homemaking are affirmed, the misogynist temptation of transgenderism will lose its appeal for girls.

Shrier is a fine journalist who has done an immense amount of research. Her extensive footnotes alone are valuable. She has written a very readable book that shows compassion for adults who have “transitioned,” for the girls who are currently suffering, and for their parents.

Antonio Malo’s book is more theoretical than Shrier’s. It delves into the Marxist roots of the feminist movement from which the transgender movement sprang. It also looks at the meaning of sexuality and judges transgender ideology according to natural and Christian criteria.

Malo traces the path to our current sexual confusion from Engels, who viewed marriage as an institution that systematically oppresses women, to Freud, who viewed sexual restraints as social constructions that threaten mental health, to Wilhelm Reich, whose books intended to liberate youth from sexual repression and the authoritarianism of the family. All of these ideas led to the Sexual Revolution of 1968 and beyond.

But the radical overturning of sexual mores was not only the work of men. Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal work, The Second Sex (1949), both guided the revolution and began the radical feminist movement. She argued that all erotic relationships are an attempt of the man to absorb the woman into his own universe and reduce her to an object of ownership. Shulamith Firestone, writing twenty years later in The Dialectic of Sex, called for women to free themselves from reproduction and childcare with new technologies and institutions so that biological differences would have no more significance in society. According to Malo, the next step, following poststructuralist thinkers like Foucault,[1] is gender feminism, which maintains that sex is purely a social construct. Judith Butler, the voice of gender feminism, writes, “When the constructed status of gender is theorized as radically independent of sex, gender itself becomes a free-floating artifice, with the consequences that man and masculine might just as easily signify a female body as a male one, and women and feminine a male body as easily as a female one.”[2] Sex is now meaningless or reduced to a trite stereotype; “gender” is completely detached from nature and the body, open to all linguistic manipulation. If sex does not have to do with generative organs and procreation, then it is reduced to a stereotype. Feeling female means liking pink dresses and ballet rather than rifles and engineering. But the result seems to make gender meaningless. How could a hundred “genders” mean anything but flux and confusion?

Malo agrees with feminists that there was a false and destructive paradigm for understanding man and woman, which he calls “naturalistic monism.” This paradigm absolutized the difference between man and woman according to their biological role in reproduction. Men took the dominant role in marriage, family, and society, reducing women to passive submission in every arena. They were confined to the domestic sphere, bearing children and caring for them, their husband, and the home.[3] Malo sees the first feminists as “equality feminists” who were justly seeking equality of legal rights and job opportunity. It was radical feminism and gender feminism that moved from seeking equality between the sexes to unhinging sexuality from biology. Radical and gender feminists replaced “sex” with the concepts of “gender” (formerly only used in grammar) and sexual orientation, which—in their view—are both socially constructed.

Malo points out that the very idea of sexual orientation involves a paradox.

For, on the one hand, sexual orientation seems to be unnatural because it is unrelated to bodily sex, at times failing to correspond to it; and, on the other hand, it does not seem to be personal, because it precedes one’s own choice of membership of a specific gender, insofar as it is something we have, without having wanted to have it…. Moreover, the things that seem most personal, such as choice of gender, are really the things most subject to fashion, social pressure, and stereotypes; hence, the sort of gender we choose is never purely the creation of our own freedom; we choose a template from among those on offer.

In contrast to this confused and contradictory view, Malo insists that the most important path for understanding our sexed condition is generativity. We are always generated from two persons who are male and female; we recognize that we owe our life to another—it is a gift—and we are grateful for it. We show this gratitude above all by passing on this gift to the next generation by our generative relation with someone of the opposite sex. Malo insists that parents need to educate their children to reality, including the reality of their sex, with its foundation in their body, and their place in their genealogy.

He explains the Christian account of sexual difference as one “of reciprocity between two persons of equal dignity, who are called to communion through the mutual gift of self.” When two persons desire to produce children outside of this marital gift of self, the gift-character of the child is lost as well: “They are no longer the fruit of the spouses’ mutual gift, but a chance occurrence or a product—however precious they may be—to be acquired with the aid of the new biotechnologies.” Malo’s judgments on bio-tech interventions in conception flow from his Christian understanding of the beauty and positivity of sexuality and marriage.

Malo also helpfully exposes many of the fallacies of transgender ideology and traces their philosophical and historical roots; however, there are a number of difficulties with Malo’s book. The prose is sometimes obscure; the metaphysical discussion of person, essence, and existence is weak, as is his grasp of Aristotle’s and Aquinas’s understanding of natural inclinations. I find Malo’s concept of “the sexed condition” especially troubling. He concedes that the way we integrate sexuality into our personality depends on other factors besides our biological sex, most importantly relations with other persons and our culture’s expectations about roles for men and women. Malo argues that

human sexuality must be considered rational or even better, relational in itself, because it corresponds to a potentiality of the whole person. I am referring to its malleable nature in terms of our first encounters with the other, of our relationships with internal family models, and of language and culture. In short, sexed tendency is not mere vegetative dynamism, but a structure of body, mind, and soul that is relational in character: a sexed condition.

Malo may use this concept partly to account for the fact that some persons, because of abuse or peer contagion, become convinced that their “gender” does not correspond to their sex. However, the reference to the “malleable nature” of human sexuality is potentially worrisome. It seems to contain the danger that a person could say that, despite their biological sex, other factors have made their “sexed condition” the opposite of their generative organs. I would prefer to say that the development of a person’s self-understanding of his or her sexuality is able to be distorted but I would not want to name this false understanding of a person’s sex their “sexed condition.”

Malo also gives away too much by talking about the errors of “naturalistic monism” and contrasting “nature to person” as though philosophers who equate “natural” with the bodily or animal side of man are correct. Man is a rational animal, so reason and voluntary activity is what is most natural to man. Sexual activity is in accord with human nature when it is embedded in the permanent relationship of mutual self-gift in marriage, open to the gift of children, rather than when it is engaged in out of an instinct for pleasure.

There are also certain natural qualities and roles belonging to women, flowing from their mode of being embodied persons. St. John Paul II, in his apostolic letter On the Dignity and Vocation of Women, talks about the spiritual and psychological effect of having a body built around a womb designed to welcome a new human person into the world. There is a natural reason behind the fact that, statistically, women overwhelmingly prefer people-oriented jobs to those in STEM fields like mathematics, engineering, and computing. Of course, women should not be forced to stay at home and have babies, but even many of the “equality feminists” did not only seek justice, but also undermined an appreciation for the role of mother, educator, and creator of a home. What Malo says of gender feminists could very well be applied to most feminists, “For the model to be copied is always the same: it is the male one, characterized by freedom from generation and the duties relating to the care of children.”[4] It is, to borrow Karl Stern’s apt phrase, a “flight from woman.”

The psychic alienation experienced by “transitioning” girls is also a flight from woman, born of the same fallacies that gave rise to the sexual revolution and radical feminism alike. In the end, the basic response to each of these movements is the same: a return to woman. A return to the wholeness of a body and soul integrated so harmoniously that it can receive, give, and nurture human life.

[1] Foucault makes the claim that sexuality is a construct of power and can be changed by changing language.

[2] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), 6 as quoted in Malo, 48.

[3] An exception, Malo points out, is Medieval Christendom where certain women, like abbesses, were vested with tremendous responsibilities.

[4] Malo, 90.