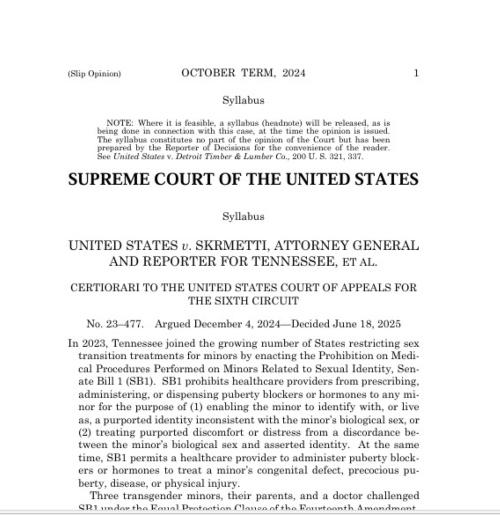

The Tennessee law challenged in Skrmetti banned “[p]rescribing, administering, or dispensing any puberty blocker or hormone,” for the purpose of (1) “[e]nabling a minor to identify with, or live as, a purported identity inconsistent with the minor’s sex,” or (2) “[t]reating purported discomfort or distress from a discordance between the minor’s sex and asserted identity.”[1] The law called these “medical sex transition treatments.” Their proponents asserted that they are needed to alleviate sundry “distresses” arising from mind-body incongruence, including anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. Defenders of Tennessee’s law maintained that the potential risks of these treatments and the likelihood of their being unnecessary for many—those who would later feel regret and “detransition”—were greater than the benefits.

The Supreme Court upheld the statute against constitutional challenge in an opinion written by Chief Justice Roberts, to which five Justices subscribed in whole and to which Justice Alito subscribed in part.

The Skrmetti result is praiseworthy and a great relief. A contrary ruling would have exposed children not only in Tennessee but across the country to experimental treatments with extensive side-effects and with no proven benefits. The outcome augurs well, too, for the nationwide inhibitions of Executive Order 14187 “Protecting Children from Chemical and Surgical Mutilation,” which declares that “it is the policy of the United States that it will not fund, sponsor, promote, assist, or support the so-called ‘transition’ of a child from one sex to another.”[2]

The Skrmetti opinion is nonetheless disappointing. The Court did not take sides in the parties’ dispute about whether the transition procedures help or hurt addled minors or whether repudiating one’s sex to live as another sex is good or bad for children. The majority asserted instead that “we afford States wide discretion to pass legislation in areas where [as here] there is medical and scientific uncertainty,” thus signaling that it would uphold a properly drafted statute permitting what Tennessee banned. Skrmetti did not even hold that state bans on minors’ medical transitioning were constitutional. The Justices decided only that there were no Equal Protection limits upon enforcement of Tennessee’s law.[3] The Skrmetti opinion provides little guidance to lower courts handling disputes about other transgender issues, such as bathroom access and the suite of items addressed by Trump Administration Executive Orders concerning the military, federal prison housing, passport identifications, and sports competitions.

There is much to be said in favor of constitutional adjudication that decides the case at hand on grounds no broader than necessary. Skrmetti pursues this line to a fault: it is studiously crafted to be a one-way ticket, good for this ride only. But the judicial obligation is not to say as little as possible. It is to decide cases on the basis of principled, reasoned judgments and to thus adequately decide the issues presented. The Skrmetti Court repeatedly ducked questions squarely presented and artificially trimmed its reasoning to avoid overt resolution of deeper questions—again, squarely presented—about transgenderism and the Constitution. Such judicial trimming not only risks clarity, cogency, and coherence, but also gives the appearance of a results-driven decision, which is precisely what the trimming is probably meant to avoid.

I.

The plaintiffs in Skrmetti mounted twin equality-based complaints, namely, that the law discriminated on the basis of sex and also on the basis of transgender identity. The Court rejected both allegations, saying that neither discrimination was present and that there was therefore no basis for “heightened scrutiny” of the Tennessee law.

The opinion is strongest where the Court refutes the claim that the Tennessee law discriminates on the basis of sex—here clearly referring not to “gender” but to the biological fact that the human species is comprised of males and females, with no remainder. The plaintiffs claimed the authority of Bostock v. Clayton, the 2020 Title VII employment discrimination case that, in a Gorsuch-opinion for the Court, seemed to say that prohibited sex discrimination occurs where one cannot understand the content of a legally operative proposition without understanding what sex means.

The Chief Justice recounted how the Skrmetti plaintiffs fired both of its sex-discrimination barrels:

The plaintiffs … argu[e] that SB1 creates facial sex-based classifications by defining the prohibited medical care based on the patient’s sex. … This argument takes two forms. At times, the plaintiffs suggest that SB1 classifies on the basis of sex because its prohibitions reference sex. Alternatively, the plaintiffs contend that SB1 works a sex-based classification because application of the law turns on sex.

[T]he plaintiffs urge … [that] SB1 violates the Equal Protection Clause because it prohibits a minor whose biological sex is female from receiving testosterone to live as a male but allows a minor whose biological sex is male to receive testosterone for the same purposes (and vice versa). Applying Bostock’s reasoning, they argue that SB1 discriminates on the basis of sex because it intentionally penalizes members of one sex for traits and actions that it tolerates in another. [4]

Roberts wrote for the majority in response:

Neither argument is persuasive. … Notably absent from their framing is a key aspect of any medical treatment: the underlying medical concern the treatment is intended to address. … Different drugs can be used to treat the same thing (would you like Advil or Tylenol for your headache?), and the same drug can treat different things (take DayQuil to ease your cough, fever, sore throat, and/or minor aches and pains). For the term “medical treatment” to make sense of these various combinations, it must necessarily encompass both a given drug and the specific indication for which it is being administered.

This is spot-on correct. The Chief Justice here is doing no more, but no less, than observe that the same behavior may be, and commonly is, many different human acts. Just as the observable physical motion of, say, inserting a sharp steel object into a person’s abdomen—as if one were watching snippets of a silent movie—could be the opening stage of a bowel resection, or a criminal assault, or a bizarre religious ritual, or a desperate attempt to retrieve a swallowed gem, or part of “gender-reassignment” surgery, so too could the physical activity of giving puberty blockers be a proper treatment for precocious puberty or a misguided effort to abet sex-transition (or, I suppose, a means of assaulting a rival adolescent or of punishing a persistently misbehaving child).

Human acts are typically comprised of behavior joined to an often-complex mental state. A human act is specified—understood as the precise act that it is—by virtue of its object. It is human action, not chunks of behavior, that SB1 regulates. And once the acts prohibited by SB1 are accurately identified, it is easy to see that (1) they do not discriminate on the basis of sex—neither boys nor girls may be exposed to the same medical acts, and (2) that, although the prohibitions cannot be understood without understanding what sex (male or female) is, we can now see that reliance upon the meaning of “sex” for the intelligibility of a proposition is not itself a “suspect” classification of any kind.

The act-analysis deployed by the Skrmetti majority is no philosophical colonization of proper legal thought, an invasion of law’s rightful autonomy as the limited and largely technical form of practical reasoning that it is. The Chief Justice rather summoned a piece of elementary legal learning, a standard part of the lawyer’s tool kit, the bread-and-butter especially of those who enforce criminal laws. For the staple of criminal law is understanding exactly what people may and may not do according to deftly composed statutes which join specified human behavior (say, throwing a rock or sticking your hand in someone else’s pocket) to particular intentions (say, trying to break your neighbor’s window or with intent to remove a wallet).

But note well: the act-analysis in Skrmetti limits the cogency of the Court’s rejection of the plaintiffs’ sex-discrimination claims to a specific medical context and its concrete treatment by the Tennessee legislature. The act-analysis itself is portable. The results of its application in Skrmetti are not.

II.

Three members of the Skrmetti majority evinced a willingness to foreclose the other ground for heightened scrutiny pressed by the plaintiffs. They would conclude in a case properly presenting the issue that the “transgendered” are not a suspect class and that laws which rely upon that classification do not trigger “heightened” judicial scrutiny. Two of these three (Justices Barrett and Thomas) joined the Court’s opinion that the Tennessee law did not raise that question: “This Court has not previously held that transgender individuals are a suspect or quasi-suspect class. And this case, in any event, does not raise that question because SB1 does not classify on the basis of transgender status.” Justice Alito would have decided the issue on the facts of Skrmetti.

The Court’s teaser for its dismissal sounds like an act-analytical refutation: “As we have explained, SB1 includes only two classifications: healthcare providers may not administer puberty blockers or hormones to minors (a classification based on age) to treat gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, or gender incongruence (a classification based on medical use).” The Court successfully defeated the sex-discrimination charge by showing that, although one could not understand the Tennessee law without relying upon a proper understanding of “sex” as male or female, the relevant prohibited act was the same for both boys and girls. But it is not at all apparent that the same could be said of SB1 and “transgender.” The Court’s reasoning on this point did not clarify the picture.

The Skrmetti Court recognized that “only transgender individuals seek puberty blockers and hormones” for the statutorily excluded purpose, basically, to abet the transition to being “transgendered.” The opinion continued:

[The law] does not exclude any individual from medical treatments on the basis of transgender status but rather removes one set of diagnoses—gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, and gender incongruence—from the range of treatable conditions. SB1 divides minors into two groups: those who might seek puberty blockers or hormones to treat the excluded diagnoses, and those who might seek puberty blockers or hormones to treat other conditions. Because only transgender individuals seek puberty blockers and hormones for the excluded diagnoses, the first group includes only transgender individuals; the second group, in contrast, encompasses both transgender and non-transgender individuals. Thus, although only transgender individuals seek treatment for gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, and gender incongruence … there is a “lack of identity” between transgender status and the excluded medical diagnoses.

This entire paragraph and particularly its concluding sentence are baffling. Medical transition treatments are downstream from not only a diagnosis of “gender dysphoria”—clinically significant “distress” arising from mind-body incongruence—but also from a decision by the responsible guardian that the minor is at least proto-“transgendered”; that is, prepared to repudiate his or her sex, to begin identifying as a member of the other sex, and to take medical steps to promote that transition. Only then do the medical transition sex treatments commence. They are defined by statute as the administration of drugs [to a proto-transgendered minor] to “enable” passage from “proto” to “in fact.” If that does not make the Tennessee law one that classifies on the basis of “transgender” “status,” I do not know what would. [5]

The Court analogized its declaration that the state law was innocent of a “transgender” classification to one of its most prominent sex-discrimination cases, Geduldig v. Aiello. There the lawmaker excluded from insurance coverage certain disabilities that resulted from pregnancy. Plaintiffs in that case maintained that, because only women could get pregnant, this was rank sex-discrimination. Skrmetti, again:

Because women fell into both groups, the program did not discriminate against women as a class. We thus concluded that, even though only biological women can become pregnant, not every legislative classification concerning pregnancy is a sex-based classification. As such, “[a]bsent a showing that distinctions involving pregnancy are mere pretexts designed to effect an invidious discrimination against the members of one sex or the other, lawmakers are constitutionally free to include or exclude pregnancy from the coverage of legislation … on any reasonable basis, just as with respect to any other physical condition.” [Citations omitted] By the same token, SB1 does not exclude any individual from medical treatments on the basis of transgender status. [Emphasis added]

The italicized move is mysterious. It appears to be no more than an ipse dixit. Beyond that, the Chief may have torn asunder what he joined together to defeat the sex-discrimination claim, recounted here in Part I. Then the relevant act was rightly identified by its intended object or purpose: to enable transition to a “transgender” identity (a boy, say, “presenting” as a girl). Now the object/purpose is occluded and the partnership is between the not-yet-an-act pharmaceutical behavior—the administration of “puberty blockers or hormones”—and “excludable diagnoses” (“gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, and gender incongruence”).

The Court here eschews any moral evaluation of transitioning itself. The problem (as the Justices evidently see it) is that the transition cannot be managed safely.

A “diagnosis” is not nearly the same thing as the “purpose” of a medical intervention. “Diagnosis” refers to an existing condition. The “purpose” of a medical protocol is to substitute a different state of affairs for that condition. A “diagnosis” explains and justifies a particular medical intervention. To identify that intervention as an act, however, one needs to connect the raw medicalized behavior to an object, a purpose, a desired end-state-of-affairs. No “diagnosis” supplies that.

The Court added that the plaintiffs “have not argued that SB1’s prohibitions are mere pretexts designed to effect an invidious discrimination against transgender individuals.” It is hard to fathom this reply. The plaintiffs made no “pretext” argument because they say the law baldly discriminates against “transgender” minors. The Court rejected that position, however unconvincingly. But having done so, it seems rather more plausible (and fair) to then attribute precisely such a “pretext” argument to the plaintiffs—and then to meet and resolve the question at hand.

III.

Chief Justice Roberts concluded for the Court in Skrmetti that “SB1 does not exclude any individual from medical treatments on the basis of transgender status.” “Status” is the evaluative fulcrum in this sentence. The Court did not say what it means by “status.” That is unfortunate. Leaving the matter unexplored is also an opportunity missed to discredit the broad position of advocates who claim that one discovers, over and against the “sex one was assigned at birth,” one’s real identity in one’s mind and heart and psyche, hidden there among the brambles of the wrong body and misplaced social gender expectations. Most important, any critical look at what “status” could mean in the “transgender” context would have shredded any argument that it is a “suspect” classification.

“Status” is, legally speaking, multivocal. Many uses of the word in the law refer to projects freely chosen and eventually completed, often with great concentrated effort; for example: veteran status or that of a college graduate. Sometimes the status is earned at a moment in time but is renewed continually; thus, marriage. In criminal law there is a taboo against making status, as opposed to actions, a crime. Thus, drug addiction, alcoholism, and homelessness are statuses which are immune in themselves to criminal liability. But each of these statuses is largely the culmination of a sequence of choices stretching over a long time, perhaps decades. These statuses are reversible.

The central sense of “status” in the Court’s suspect class jurisprudence refers to an innate and immutable quality, such as race, ethnicity or sex: things no one can choose to be or cease to be. These traits are not only indelible. They are also rarely, if ever, relevant to any legitimate lawmaking purpose. That is what makes race, sex, ethnicity suspect legal classifications: people are utterly blameless for their race, sex, parentage. Such unchosen traits—though often the stuff of gross prejudice—do not often, if ever, provide a reason to treat people differently.

“Transgendered” is nothing like any of these canonical “suspect” classes. Felt incongruence between one’s self-perception and one’s body (such as anorexia, body-integrity disorder, or gender dysphoria) is a condition more or less unchosen. The same is true for clinically diagnosable stress resulting from these conditions. In each instance, however, the felt helplessness of the moment is not inconsistent with recognizing that a host of choices by minors and parents contribute to it, as they do to so many other childhood conditions, such as obesity or impulsiveness, and as they do to narcotics addiction, alcoholism, homelessness.

We are not yet talking about transgender status. Many gender dysphoric people, including most children suffering from it, are not “transgendered.” To occupy that status one has to choose to repudiate one’s sex. One must then choose to “identify” as a member of the opposite sex. Then one must choose to undergo bodily changes such as those banned in Tennessee.

Someone who sees transition through to this point might well be labelled as “transgender.” If it is to be called a “status,” it is surely an unstable one, for “gender identity” is a fluid self-perception. There are many formerly “transgender” people who have repudiated their prior repudiation of their sex and who have resumed living as the boy or girl he or she is. All of these choices are subject to critical moral judgment, favorable or otherwise. The resulting condition of alienation from one’s natal sex can also be judged as harmful or deleterious.

Even this shallow dive into what the Chief Justice called “transgender status” reveals that the concept is evanescent and that, insofar as it can be brought into focus, the claim that it is a “suspect class” like race, ethnicity, or sex is not even plausible. The Skrmetti Court had insufficient reason to avoid saying so.

IV.

The Skrmetti Court wrote: “Having concluded [Equal Protection] does not [impede enforcement of Tennessee’s law] we leave questions regarding its policy to the people, their elected representatives, and the democratic process.”

This thought is jejune. Because the Court said nothing about the parents’ rights constitutional claims adjudicated by the Sixth Circuit it is premature to say that the federal judiciary is done with the matter. The thought is expressly limited to the “policy” of “its” (i.e., Tennessee’s) law. Two Justices in the majority widened the scope of the thought to where the majority opinion ends up by applying the lax “rational basis” test: the set-piece battles of scientists, doctors, philosophers, and politicians over “transitioning” minors—“policy”—is to be resolved by “the people, their elected representatives, and the democratic process.”[6] The Skrmetti Court signaled plainly that they would uphold state laws permitting the medical transition treatments banned in Tennessee. The Court is saying that public authorities in America may do what Tennessee did, not that they must.[7]

That parity or neutrality is jejune, too. For one thing, approving a prohibition does not imply approving a permission. The Supreme Court has no authority, moreover, to declare that any issue presented by the transgender movement is assigned to the “people and their elected representatives” by the federal Constitution. Any state court could read its state constitution to withdraw the question of medical sex transition treatments from the “democratic process,” judging either that the state constitution either bans them or sanctions them. The Court said the same thing about assigning abortion “to the people and their elected representatives” in Dobbs (2022). Since then, many state courts decided to find abortion rights in their state constitutions.

Besides, the Court presumes, though neither decides nor argues, for the conclusion that permissive state laws would trigger “rational basis” scrutiny. To competently establish that conclusion, however, the Court would have to exclude all plausible bases for triggering “heightened” scrutiny. The Skrmetti Court made no effort to do so. That the Constitution itself might shield minors from these medical treatments seems never to have occurred to the Justices.

Here is one such basis: to get to the “rational basis” destination the Justices would have to establish that the permitted procedures do not constitute mutilations—just as the Trump Administration asserts that they are in Executive Order 14187. For if they are mutilations, then the Equal Protection Clause would presumptively require the states to enforce their criminal laws against child abuse, assault, genital mutilation (among other offenses) against anyone—parents and doctors included—who mutilate a minor child. In this way of looking at it, states would have no more constitutional authority to permit the medical mutilation of children who imagine that they are members of the other sex than they do to permit parents of children suffering from Body Integrity Disorder—kids with intact limbs who identify as amputees—to have an arm or a leg surgically removed. In both cases doctors and parents would argue that they are acting in good faith to relieve severe “distress” caused by a body that does not conform to the minors’ understanding of his or her identity. No matter. It is still a crime.

Skrmetti resolved the question presented about state bans and Equal Protection on defensible grounds without deciding about mutilation. But that supplied no basis for endorsing permissive state laws, especially since no party to the Skrmetti litigation bore the burden of argument on the point. The mutilation question will have to be resolved in any competently litigated challenge to a permissive state law by someone acting for a minor facing such “medical” procedures, or who suffered them and is now suing for damages for medical malpractice. The Court in Skrmetti imprudently, and gratuitously, pre-judged this (these) question(s).

Now, the Trump Administration by Executive Order 14187 describes as “chemical and surgical mutilation” the “use of puberty blockers, including GnRH agonists and other interventions, to delay the onset or progression of normally timed puberty in an individual who does not identify as his or her sex; the use of sex hormones, such as androgen blockers, estrogen, progesterone, or testosterone, to align an individual’s physical appearance with an identity that differs from his or her sex; and surgical procedures that attempt to transform an individual’s physical appearance to align with an identity that differs from his or her sex or that attempt to alter or remove an individual’s sexual organs to minimize or destroy their natural biological functions.” But are these dramatic medical procedures properly characterized as acts of “mutilation”?

For starters it is important to note that an act of “mutilation”—just as any other criminal act—can be performed with good motives: a husband might beat up the gigolo who cuckolded him as a fit punishment for home-wrecking; a thief might rack up robberies to get the money he needs for his family, or for his tuition bills, or for his mother’s medical expenses (or to feed his drug habit); abortionists might think that they are helping women they illegally abort; defense researchers who reveal state secrets might think they are helping the American people; a father who directs the genital mutilation of his young daughter could think that he is helping her to live chastely and, perhaps, that he is doing as God wishes him to do. Perhaps there are even a few simple-minded Christians who take the Lord to be speaking a literal truth when he warned, in the Sermon on the Mount: “If your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell.”

All of these actors commit crimes, notwithstanding the hypothesized honorable motives and/or downstream objectives. It is still a matter of doing evil that (by hypothesis) good may come of it.

Medical sex transition procedures are decisively unlike other physically deforming medical procedures such as amputation of a gangrenous limb where the amputation is just a behavioral component of a medical act that is describable, morally, as life-saving. Transition procedures are unlike other cases of prescribing, say, a psycho-active pill with an almost certain physical side effect, such as temporary or even permanent sterility. In those cases, the hypothesized sterility is not part of the doctor’s plan or intention and thus not part of the act he carries out. They are side effects. Transition procedures are not cosmetic surgeries either, despite some superficial similarities. Even assuming that cosmetic surgery for children is morally permissible, those operations rarely if ever mutilate; that is, do anything to damage one’s integral organic functioning as a healthy individual. Besides, cosmetic surgeries have far fewer and much better-know potential side effects. That is surely not true with the pharmaceutical and surgical interventions intended to align a child’s healthy body with a discordant gender identity.

In “sex change surgeries” as well as in pharmaceutical efforts to stymie puberty and to suppress natal sex characteristics and promote the appearance of those associated with the other sex, the mutilation is surely intended. These procedures cannot really change anyone’s sex. Their purpose therefore is to give a person the feeling or subjective perception of being of the sex that is different from his or her real sex. But that feeling or misperception is itself a disharmony between his or her self-perception or emotional acceptance, on the one hand, and his or her actual body. Instead of the harm being a side effect (as is the case with say castration in a prostate cancer case) the disharmony or alienation or discordance between mind/self and body is intended, as is the disfigurement and other “mutilative” effects of these interventions.

So, what the Trump Administration calls “chemical and surgical mutilations” are just that. Mutilation of children is a crime (child abuse, assault) in every state. These laws are not rendered inapplicable and no immunity is created by worthy motives or asserted, hoped-for, eventual benefits. A permissive state might try to avoid the obvious equal-protection problems of not enforcing criminal laws here by enacting a new law saying that, although these procedures are mutilations, they are nonetheless justified. But this move merely kicks the constitutional problem-can down the road: the enactment would codify what formerly would have been an executive policy. Both are equally governed by the Equal Protection Clause. The move gains no more traction against an equality-based constitutional objection than would enacting a law that codified the sheriffs’ prior policy of not enforcing rape laws, for example, in cases where black women are the victims of white men.

V.

The Skrmetti plaintiffs opened a second front in their fight for sex-discrimination heightened scrutiny: “sex stereotyping.” The classic Supreme Court decision is an employment case, Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (1989). There, a female worker suffered adverse treatment due to her failure to act “feminine” enough in her dress, deportment, and affect to suit those in charge. Here and elsewhere in the law “sex stereotype” discrimination cases present scenarios in which females, for the most part, fail to conform to social expectations of womanly appearance and behavior. But men can be and sometimes are victims, too.

In Skrmetti the plaintiffs and the dissent maintained (in the Chief Justice’s recounting of it) that

the legislatures’ “finding” that it “has a compelling interest in ‘encouraging minors to appreciate their sex’ and in prohibiting medical care ‘that might encourage minors to become disdainful of their sex’” operates to force conformity with sex.

“Force conformity with sex” is a nonsensical proposition. That is because—as the Supreme Court itself has affirmed repeatedly in season and out of season—sex is innate, binary, and immutable. In Skrmetti itself the discussion of “suspect classes” implicitly maintained what Justice Barrett made explicit in her concurrence: transgender is not like sex, for sex is “immutable.” Being transgendered is not. In Skrmetti the Justices all presupposed that, notwithstanding manifold possibilities for “gender,” there are but two sexes: male and female. In other cases, the Court has recognized that what it calls “biological” sex is male or female from the beginning and forever. It is impossible not to “conform[] to one’s sex.”

Denying that sex is innate, binary, and immutable is a non-starter. There is no rational basis for denying any one of those three truths.[8]

Holding tight to these truths is especially critical in the practice of medicine, including in “medical sex transition procedures.” Any doctor “transitioning” a boy to being a “girl” who actually treated his patient as if he was a girl would be guilty of malpractice. For sex is not just about genitalia or other obvious physical indicators of being male or female. Each and every cell of a woman’s body is female. Each and every cell of a man’s body is male. While the commonalities and similarities of men and women still far outweigh the differences, keeping in mind the differences is essential to sound research and competent medical practice. It is therefore unsurprising that the National Institutes of Health now requires consideration of sex in its life sciences research proposals. The NIH states that “[t]here is growing recognition that the quality and generalizability of biomedical research depends on the consideration of key biological variables, such as sex.” “Failure to account for sex as a biological variable may undermine the rigor, transparency and generalizability of research findings.”

Tennessee limited its prohibition to minors. There are many stereotypes about how a twelve-year-old boy, for example, should behave in our society and they are very different from those about nineteen-year-olds. No matter how mature the younger boy looks, acts, and thinks, and whether or not he conforms to any stereotypes, nothing can change the fact that he is, actually, twelve. It makes as much sense to say that a boy was born in the wrong body as it does to say that he was born in the wrong year. It makes as much sense to say that SB1 “forces” a boy to “conform[]” to his sex as it does to say that it is forcing the same boy to conform to his age.

If Tennessee is guilty of anything here, it is of enforcing the unexceptional proposition that boys are boys, and that is just the way things are.

The Chief Justice also observed that the “stereotype” charge is misplaced. His elliptical expressions in support obscure what he means. His clinching point is this: “[W]here a law’s classifications are neither covertly nor overtly based on sex, we do not subject the law to heightened review unless it was motivated by an invidious discriminatory purpose … No such argument has been raised here.” This, too, is unconvincing.

Any court presented with an argument that is “misplaced” in this most fundamental way should say so straightaway. Doing so would nip a frivolous line of arguments in the bud. This sort of category mistake takes priority in sound judicial reasoning over the consideration of instances within the errant category. Doing otherwise would be like sending to a jury a case about whether a comatose person committed a rape. In truth, there is no need to consider evidence of guilt, once it is clear that the defendant was incapable of acting at all. For one must act in order to be guilty of a crime. The Skrmetti Court sent the case to the jury.

One could imagine a different, non-frivolous argument which retains some of the rhetoric of “sex stereotype.” One would get this argument off the ground by conceding (as one must) that sex is innate, binary and immutable and thus that my (or your) body is indelibly male (or female). Then one could imagine that one’s indelibly sexed body is not me or part of me. One would claim that one’s body is instead an accoutrement of one’s real self, which is a matter of spirit/psyche/mind.

The Skrmetti plaintiffs made no argument based upon such a metaphysically dualistic account of the human person. This would have been appropriately cast aside by the Court, probably in a footnote, as not presented for evaluation in this case.

Finally, the Skrmetti Court concluded that “the statutory findings to which the plaintiffs point do not themselves evince sex-based stereotyping.” The Court added:

The plaintiffs fail to note that Tennessee also proclaimed a “legitimate, substantial, and compelling interest in protecting minors from physical and emotional harm.” And they similarly fail to acknowledge that Tennessee found that the prohibited medical treatments are experimental, can lead to later regret, and are associated with harmful—and sometimes irreversible—risks.

The Court here eschews any moral evaluation of transitioning itself. The problem (as the Justices evidently see it) is that the transition cannot be managed safely. Unless the Justices suppose that some dualistic account of the human person is true, however, they could not view with equanimity sex-transitions in themselves. For then it would be self-evidently the case that anyone who repudiates his sex rejects his body and thus divides himself. This condition of personal disharmony and alienation cannot be judged as anything less than a privation, a harm, simply bad.

VI.

It is true as a general matter that courts, including the Supreme Court, should decide the cases that litigants put before them. In other words: parties and not judges shape cases for decision. There are many qualifiers to be added to this general truth, though. Not least among them is that the general norm does not lessen a court’s obligation to decide the issues it chooses to decide on the basis of sound principles and reasoning, at the depth needed to do so cogently, and to have due regard for truths of justice that might not be conventionally understood as part of conventional legal learning.

Even so, someone might object that, notwithstanding some missteps and some trimming, the Supreme Court decided Skrmetti pretty much as the parties presented it—and good for that! Leaving aside the accuracy of this claim, I should like to point out here how it subsists on a trick. Litigators litigate to win. To do that they have to know their audience, in this case the federal courts under the authority of the Supreme Court. It is therefore likely that Tennessee’s stated legislative purposes, which coyly nest normativity about sex and gender within an overarching story about uncontroversial medical and emotional harms, is more a litigation posture than it is an accurate reflection of what the lawmakers actually thought. They were probably advised by their lawyers from the get-go that the Court’s conservatives, who would otherwise be sympathetic to SB1, would not take kindly to frank moral and metaphysical normativity. The Skrmetti opinion vindicates this hypothesized advice.

The “trick” therefore is that, before the parties shape the litigation, the courts shape it by establishing what counts as a sound form of argument, what does not, what sort is off-limits and what lies in the sweet spot of the pertinent judicial temperament.

I have labored at length elsewhere to show how the Court’s conservatives have come to be nearly allergic to critical morality, metaphysics, and other matters philosophical.[9]

Two other powerful currents of constitutional law, neither put in place by conservative Justices, shaped the parties’ litigation in Skrmetti. One is the elephant hiding in plain sight: the prospect that the self-reported “truth” of, say, a twelve-year-old boy whose parents would not let him choose his own bedtime and whom the law does not allow to get a tattoo, could command a suite of medical services to facilitate the dream of living as a girl. Neither the courts nor the legal system created this science-fiction scenario. Derailments across the culture and in the education system, and a medical establishment overtly ideologized, all contributed to it. But the law shapes as much as it reflects culture, education, and ideology.

The litigability of the science-fiction scenario is, in any event, unimaginable save as the downstream effect of the Court’s infamous paean to subjectivity, the “Mystery Passage” of Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992): “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Here a putative authenticity supplants reality. The value of what one holds depends upon it being mine, really me holding it, autonomously, as it were. Whether what one holds is true is insignificant.

The other current is comprised of two landmark cases, Lawrence v. Texas (2003) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), where the Court decapitated the real-life normativity upon which the importance of living peaceably with our sexed bodies depends: sex and marriage. Both cases cited and relied upon the Mystery Passage. Lawrence was about two men and their private sodomitical acts. The Court decided, for the first time, that consent would be the legally enforceable moral principle governing private sexual acts between and among grown-ups. Obergefell of course established same-sex civil marriage. Together, these cases yield the following proposition of constitutional law: sexual acts, marriage, and human reproduction are androgenous. Participation across the board in these sublime undertakings no longer depends—as it did from time out of mind—upon acting as the male or female persons that in fact, we are. So far forth, it matters no longer to our law whether one engaged in these actions is or thinks one is male or female, neither or both.

“Time out of mind” was not so long ago. All the way into the twenty-first century and notwithstanding steep cultural decline, marriage as the procreative union of a man and a woman remained the relevant constitutional principle. The canonical expression of it is Justice John Harlan’s, in his Poe v. Ullman dissent:

[T]he very inclusion of the category of morality among state concerns indicates that society is not limited in its objects only to the physical well-being of the community, but has traditionally concerned itself with the moral soundness of its people as well. … The laws regarding marriage which provide both when the sexual powers may be used and the legal and societal context in which children are born and brought up, as well as laws forbidding adultery, fornication and homosexual practices which express the negative of the proposition, confining sexuality to lawful marriage, form a pattern so deeply pressed into the substance of our social life that any constitutional doctrine in this area must build upon that basis. [10]

In other words: marriage is the legally enforceable, morally normative context for having children and for having sex.

Both Lawrence and Obergefell are beyond recall for the foreseeable future. But that does not mean that their entailments are settled or even that their precise meaning is uncontestable. One important tranche of transgender cases depends, in fact, upon excavating from their detritus enough of Harlan’s worldview to pass the intermediate scrutiny test triggered by sex discriminatory public practices. I speak chiefly of bathrooms and locker rooms and other places of more or less compulsory undressing, and of access to them by members of the opposite sex who identify as transgender. (Single-sex housing, including in prisons, comes within the force of this analysis.) I speak chiefly, too, of minors, although the issues and how to resolve them correctly apply as well to adults.

A law or state policy that forbids “men,” say, to enter “women’s” intimate spaces is rank sex discrimination. What “important” government interest (to quote the prevailing expression of “heightened” scrutiny) could justify categorically excluding all members of the opposite sex? Often enough a sincere concern for females’ safety from male sexual predation is put into play. But this justification smacks of “sex stereotypical” thinking. More commonly, “privacy” concerns are put forward. Fair enough. But what specifically are these concerns? What set of values makes them so “important”?

Why should young people whose sexual urgings are yet to be fully comprehended and mastered not be forced by public authorities to strip naked with strangers of the opposite sex? This is to ask why we have sex-segregated intimate facilities in the first place. It is not mistaken to say that the reason is privacy. But it is not enough to say “privacy.” The reason for closing restrooms (and lockers and showers) to members of the opposite sex is that it is wrong to make anyone, and young people in particular, the objects of others’ sexual arousal, and to tempt them into sexual arousal. Doing that is unfair to all the students and threatens to harm them by impeding their attempts to develop chaste habits. Doing so would be morally akin to requiring high school students to sit together and watch stag movies every week. Even adults who have resigned themselves to a certain prevalence of sexual activity among teens would not facilitate co-ed porn viewing. The increased vividness accompanying real-time exposure in school makes the locker-room exposure more corrupting than the movie date, because students in these cases face the additional complication of having continued, regular contact with those of the opposite sex whom one has seen—and by whom one has been seen—naked.

These values of modesty and chastity are as old-fashioned now as is Harlan’s placement of conjugal marriage in the cockpit of public morality. These values are nonetheless essential, in my judgment, to cogently defending against transgender constitutional challenges to the privacy of bathrooms, locker rooms, and showers in public facilities. Note well: there is an undeniable hetero-normativity to it: same-sex group nudity is to be presented and cultivated as normatively non-sexual and chaste. Mixed-sex nudity is not.

Conclusion

Skrmetti manifests a curated superficiality. It seems to be motivated by the Justices’ desire to stick to legal reasoning on conventional legal materials, to avoid the alien incursion of philosophy into judicial opinion-writing, and to be or appear to be neutral on politically controverted matters of critical morality and metaphysics. These are all honorable aspirations. They should be counted, even, as ordinary virtues of constitutional adjudication by our country’s apex court. But they are penultimate values, and defeasible. None and not even all three taken together count rightly as the master criterion or the principle of Supreme Court opinion-writing. Bestowing upon these virtues paramount importance results leads to a light touch, which—we have seen—smudges objectivity, diminishes the quality of judicial craft, and gives credence to political readings of the Court’s opinions.

[1] Tennessee also banned surgeries for the same purposes, but that dropped out of the litigation picture because the plaintiffs lacked the requisite “standing” to challenge that part of the law.

[2] At least two federal trial courts have enjoined implementation of this measure on grounds addressed partly in Skrmetti, but also due to concerns about separation of powers; that is, whether the President has claimed authority over federal spending that he does not possess. This question is not touched by Skrmetti.

[3] The Court did not review that portion of the Sixth Circuit’s decision rejecting a parents’-rights claim to decide on medical sex transition treatments, including surgeries, for their child. It is unlikely that any parent-plaintiff could secure a judicial declaration that a restrictive law like Tennessee’s was unconstitutional in itself; that is, unenforceable tout court. Well-counselled parents would instead seek exemptions from any such ban for this or that specific child of theirs. The odds would be favorable. Judge Sutton wrote for the lower court that “parents do not have a constitutional right to obtain reasonably banned treatments for their children.” He argued for that conclusion convincingly enough. It is commonplace that parents may secure relief from exceptionless medical mandates, as we saw in many courts with COVID vaccine mandates.

[4] Throughout this essay internal citations have been omitted from Skrmetti. The excerpts have also been cleaned up.

[5] Justice Barrett (joined by Justice Thomas) wrote: “Beyond the treatment of gender dysphoria, transgender status implicates several other areas of legitimate regulatory policy—ranging from access to restrooms to eligibility for boys’ and girls’ sports teams. If laws that classify based on transgender status necessarily trigger heightened scrutiny, then the courts will inevitably be in the business of ‘closely scrutiniz[ing] legislative choices’ in all these domains.” Just so. It seems, however, that these laws are frank discriminations on the basis of sex and would trigger heightened scrutiny no matter what the Court says about the transgendered as a class.

[6] Accord Justice Thomas: The Court today reserves “to the people, their elected representatives, and the democratic process” the power to decide how best to address an area of medical uncertainty and extraordinary importance.” Concurring opinion at 24.

And accord Justice Kavanaugh, at least as evidenced by this exchange during Oral Argument with the State’s attorney:

JUSTICE KAVANAUGH: Just one clarification. It’s an obvious point, but I want to make sure you agree with it, which is you’re not arguing that the Constitution takes sides on this question. You, as I understand it, you are arguing that each state can make its own choice on this question.

So, from your perspective, as I understand it, it’s perfectly fine for a state to make a different choice, as many states have, than Tennessee did and to allow these treatments

MR. RICE [Tennessee’s lawyer]: Yes.

[7] Skrmetti:

The rational basis inquiry “employs a relatively relaxed standard reflecting the Court’s awareness that the drawing of lines that create distinctions is peculiarly a legislative task and an unavoidable one.” Massachusetts Bd. of Retirement, 427 U. S., at 314. Under this standard, we will uphold a statutory classification so long as there is “any reasonably conceivable state of facts that could provide a rational basis for the classification.” FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc., 508 U. S. 307, 313 (1993). Where there exist “plausible reasons” for the relevant government action, “our inquiry is at an end.” Id., at 313–4 (internal quotation marks omitted).

As we have explained, there is a rational basis for SB1’s classifications. Tennessee concluded that there is an ongoing debate among medical experts regarding the risks and benefits associated with administering puberty blockers and hormones to treat gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, and gender incongruence. SB1’s ban on such treatments responds directly to that uncertainty. Contrast Cleburne, 473 U. S., at 448 (record did not reveal “any rational basis” for city zoning ordinance); Romer, 517 U. S., at 632 (“sheer breadth” of law was “so discontinuous with the reasons offered for it that the [law] seem[ed] inexplicable by anything but animus toward the class it affect[ed]”).

It may be true, as the plaintiffs contend, that puberty blockers and hormones carry comparable risks for minors no matter the purposes for which they are administered. But it may also be true, as Tennessee determined, that those drugs carry greater risks when administered to treat gender dysphoria, gender identity disorder, and gender incongruence. We afford States “wide discretion to pass legislation in areas where there is medical and scientific uncertainty.” “[T]he fact the line might have been drawn differently at some points is a matter for legislative, rather than judicial, consideration.” Railroad Retirement Bd. v. Fritz, 449 U. S. 166, 179 (1980); see Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U. S. 471, 485 (1970) (“In the area of economics and social welfare, a State does not violate the Equal Protection Clause merely because the classifications made by its laws are imperfect.”); Lindsley v. Natural Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U. S. 61, 78 (1911) (“A classification having some reasonable basis does not offend against [the Equal Protection Clause] merely because it is not made with mathematical nicety or because in practice it results in some inequality”).

[8] “Intersex” is not an additional category that erodes our understanding of sex as male or female based on reproductive roles. “Intersex” is an anomalous condition that underscores the norm of male and female. In science, the anomalous does not disprove or subvert the normative. For example, humans have twenty-three pairs of chromosomes. The anomaly faced by persons with Down Syndrome, a third copy of chromosome 21, does not change what is true about human genetics any more than “intersex” changes what is true about sex. Indeed, the expression for those unfortunate cases confirms this typology: ambiguous genitalia or reproductive systems tell us that there can be unsuccessful assimilation to either male or female.

[9] See my “Moral Truth and Constitutional Conservatism,” Louisiana Law Review 81 (2021).

[10] 367 U.S. 497, 545–46 (1961) Chief Justice Roberts in his Obergefell dissent tellingly replaced Harlan’s references to “adultery, fornication and homosexual practices” with ellipses: “Justice Harlan explained that ‘laws regarding marriage which provide both when the sexual powers may be used and the legal and societal context in which children are born and brought up . . . form a pattern so deeply pressed into the substance of our social life that any Constitutional doctrine in this area must build upon that basis.’”