We are losing animals. I do not mean only numerically through the extinction of species. I also mean we are losing them in our understanding.[1]

If you look up the word “animation,” you may find something like the following:

Animation is a dynamic medium in which images or objects are manipulated to appear as moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited on film. Today most animations are made with computer-generated imagery (CGI).

This common usage points to the artistic simulation of a most fascinating dimension of our experience: the coherent change that is movement. But the word has other meanings, related but more essential. An animated face, for example, is expressive, responsive—lively. And of course an animal is a living creature. “Animation” primarily refers not to the imitation of motion and life but to life itself: the word derives from anima, soul, the principle of life. Naturalist Craig Holdrege does not use the word “soul” in his works of observational biology, but when he warns that we are losing animals, he is concerned precisely about our distraction from what unifies the unique self-expression of each of the earth’s profusion of living things. And this is a double misfortune, for losing animals in our understanding, itself a loss, implies a wound in our understanding as such.

What counts as knowledge of living beings is increasingly the specialized domain of analytical and technologized biosciences, which tend to parse organisms according to structures and functions, defining problems and solving them ever more minutely. For Holdrege, by contrast, an animal is not so much an object of study, to be broken down and rationalized, as another subject, revealing itself to the attentive observer in manifold dimensions rich with meaning that never quite submits to definition. The 2003 monograph The Flexible Giant: Seeing the Elephant Whole is one of his numerous studies dedicated to honing the art of observational biology, with subjects ranging from frogs, sloths, and giraffes to skunk cabbages, chicory flowers, and meadows. Based on Holdrege’s study of skeletal morphology as well as his observations of captive and wild elephants, The Flexible Giant is at once an exposition of the living body of a familiar, but perhaps not well-known creature, and a valuable meditation on being alive and recognizing life.

Holdrege points out that when we permit ourselves to be fascinated by the elephant or any living being, it makes an impression on us as a whole, as the whole being that it is. We tend to identify what makes a species particularly itself by way of a list of traits that may seem related only inasmuch as they belong to the same animal: flexible trunk, large ears, sturdy legs, tusks, trumpeting, and so on. But Holdrege suggests that we must take care not to let this wealth of detail divert us from the unity of the being before us:

The desire to see the unity of the elephant more clearly is not fulfilled by an encyclopedic compendium of facts about the elephant. The elephant is not its anatomy, nor its physiology, nor its ecology, nor its behavior; and it is not the sum of them all. The whole is not gained by piecing together parts. It is, rather, the unity of the organism that expresses itself in each one of these facets of its being.

Focusing on the parts of an animal can distract us from the distinctive character of the creature But it need not; and Holdrege shows us how to attend to details while skirting the dangers of fragmentation. His method depends upon strict disciplines, including the practice of integration, situating details within a more comprehensive sense of the creature, and the habit of employing memory and imagination to create concrete, highly articulated mental images from prior observations. These exercises lead over time to the recognition of patterns that contextualize and illuminate observations, as disparate details are seen to be saying one thing.

Thus, remarkably, in the case of the elephant, Holdrege shows how the title characteristic flexibility emerges as a governing trait of the whole animal, not just of one of its most salient features, the trunk. Holdrege begins his description of the animal with a close look at this organ, which serves both as a nose and as a kind of hand. Physical flexibility—the trunk is composed solely of muscle, no bones or cartilage—is matched by functional flexibility: through the trunk, the elephant is capable of

picking, grabbing, enwrapping, reaching, lifting, and pulling—all the while gathering food and putting it in the mouth; sucking in and spraying water into the mouth to drink; smelling with probing, searching motions; breathing, including use as a snorkel in water; spraying mud, or sand onto the skin (or onto other elephants in play); caressing, slapping, nudging, lifting, shoving, or trumpeting in social interaction.

The versatility of the trunk complements the elephant’s ponderousness, or better, discloses the special character of this creature’s immensity. Holdrege’s title, The Flexible Giant, expresses a certain paradox: this giant is huge but not ungainly, thick-skinned but not insensitive. It is, in fact, a terrifically versatile animal metabolically, able to eat a much more diverse diet than other land animals because of its strength and its reach, a unique combination of the elephant’s girth, tusks, height, and the extension, tactile and olfactory sensitivity, and fine motor skills of its trunk. For this reason, elephants can flourish in a broad range of environments and have been known to survive droughts far better than other species.

Holdrege recognizes the trope of flexibility not only in anatomical-spatial features but also in the dimension of time—that is, in the elephant’s distinctive ongoing physical growth and patterns of social behavior, which in numerous respects remain in flux throughout life. Unlike most animals, elephants continue to grow throughout their lifespans, although growth after twenty-five years slows markedly. Tusks grow throughout life, necessitating concomitant growth of the skull that must support their mass, as much as two hundred pounds. The elephant’s unique teeth—all molars—continue to erupt until the animal is forty or fifty years old, in contrast to other mammals, who generally have a static set of permanent teeth shortly after sexual maturity.

The onset of sexual maturity is very late in elephants: at twelve years in females and several years later in males, perhaps a decade later than is common for large mammals. Elephants have a pronounced matriarchal social system composed of family groups revolving around gestation, birth, and the raising of young; and the delay in sexual maturation plays into the wide variety of social roles that elephants fulfill over time. Holdrege shows this progression to be especially differentiated in the female: from the baby’s first tasks of learning, among other things, to master the use of its trunk, to a weaned four-year-old calf’s play with the other calves, to an eight-year-old female’s assistance with the care of the young, to the first birth, to mentorship of younger mothers. Males, which upon maturation become much more solitary, require mentorship both within the family group and also by mature bulls until they are sexually mature. Holdrege sees a kind of constitutional flexibility or adaptability in elephant social behavior, particularly in females, who revise their roles continually throughout life and sometimes revert to earlier roles at need. He finds it telling that animal trainers in Asia wait to train work elephants until after puberty: elephants are still teachable long after most animals would be set in their ways. The trunk, in some respects an instrumental cause of the animal’s physical flexibility, is in other respects just an expression of what is true of the elephant in its wholeness.

But Holdrege moderates his quest for unity: it would be laughable to take the elephant’s flexibility in myriad dimensions as an iron rule constraining every observation! Rather, the recurring theme of flexibility is an insight that finds substantiation from numerous directions, inviting further rumination and searching, not a definition implying closure. “As Goethe put it,” Holdrege writes, “the human tendency to take ‘pleasure in a thing only insofar as we have an idea of it’ can become tyrannical as ‘thought forcibly strives to unite all external objects.’ Ideas then become ‘lethal generalities.’” This is an ongoing peril for the biologist, Holdrege admits: “We are never freed from this problem.” The proper disposition of the observer thus involves a vigilance or ascesis, a gentle, good-humored detachment from the ideas we spin, lest we impose them upon the subject before us instead of permitting understanding to be born and grow in an ongoing conversation with this thing as it presents itself. Knowledge of the living is itself a kind of life, and it bears an ethical as much as an intellectual character.

The key to Holdrege’s distinctive approach to living things is the expressive character of the organism. He takes for granted that a living body is an epiphany, a kind of coherent word. It is an insight voiced more than a century ago by the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins:

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves—goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me; for that I came.

This cry must be received and interpreted with patient care, and Holdrege renders this reverent service admirably. Stephen Talbott, a colleague of Holdrege’s at the Nature Institute founded by Holdrege in 1998, refers to the work of that Institute as cultivating a way of knowing as a way of healing: healing the rifts modern habits of thought have imposed between organism and environment, subject and object, truth and goodness. This restoration exceeds the boundaries of animal studies, bearing resources for the renewal not only of the sciences but of medicine, bioethics, and philosophical anthropology.[2] What we stand to gain from Holdrege’s retrieval of animals is a recovery of our relation not only to elephants, giraffes, and sloths but to ourselves, rational animals whose forms are no less epiphanic.

Lesley Rice is a doctoral candidate at the John Paul II Institute for Studies for Marriage and Family in Washington, DC.

[1] Craig Holdrege, “What Does It Mean to Be a Sloth?”

[2] Both Holdrege and Talbott have made many contributions in these directions. See, for example, Holdrege’s edited collection, The Dynamic Heart and Circulation (Fair Oaks, California: AWSNA Publications, 2002) and his The Genetic Manipulation of Life (Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press, 1996). See also Talbott’s “A More Child-Like Science,” The New Atlantis (Winter 2004): 23‒31; “Getting Over the Code Delusion,” The New Atlantis (Summer 2010): 3‒27; “The Embryo’s Eloquent Form” (2008). Talbott’s brief essay, “A Way of Knowing as a Way of Healing” (1999), offers a synopsis of the Nature Institute’s work.

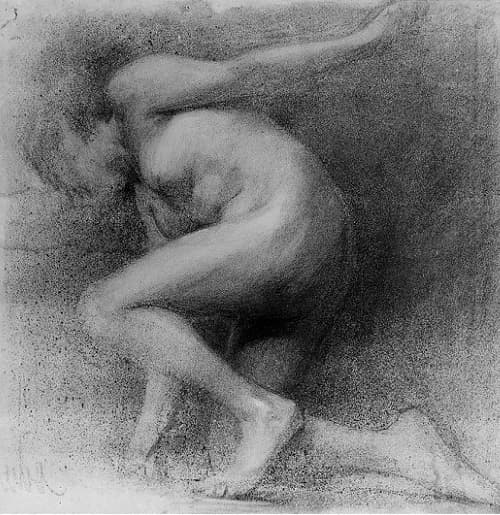

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, From Mummies to Michelangelo:Transformation of the Body in Art.