Dr Andrew Root's The Children of Divorce has provided a valuable study of the ontological fracturing that occurs for persons whose mother and father have divorced. This is an important advance in understanding the depth of the loss that divorce causes for the children of the marriage. He has pointed out that relationships of origin are an essential part of a person's being, and explains the source of this in God's inner life of Trinitarian relationships, of which the human family is an image analogically. However, there are a couple of considerations I would like to propose regarding the analogy of relationship in view of the analogy of being.

I think we all need to be grateful to Dr Root for his focus on the ontology of relationships in marriage and family. At the same time, I would like to suggest that to further this ontology there is an additional understanding that needs to be clarified and that can, I hope, augment the ministry to children of divorce and to families generally.

Here is the point I want to make: the analogy of relationships needs to be firmly grounded in the analogy of being for, if God is Being ("I Am Who Am," - God revealed to Moses), and God, the Creator, is the source of human existence, then the root of our existence is in Being and our relationship with God comes from this. (Of course, only God is Being absolutely and perfectly; humans only possess being contingently and imperfectly, which is why it is analogical and not equivalent.) But Dr Root states we need to put relationships first, before being: "It is relationship that leads to being (not the other way around)" (p. 73). I would submit that this statement is putting the matter backwards, since God as Being is the source of relationship.

It is actually not necessary to set up such a primary/ secondary order of priority. These are unified, inseparable aspects of our existence. But I think it is important, particularly for persons suffering from fractured relationships, to remember that no matter how disconnected and "unreal" one is feeling, one's being is always solidly grounded in God's Being. This is one's first relationship, and it is permanent and indestructible.

Dr Root's desire to emphasis the centrality of relationships, which is indeed necessary, has led to some loss of balance in his ontology. The source of this imbalance seems to be his dislike of the concept of substance as the basis of anthropology, with its emphasis on intellect and free will as the defining characteristics of the human being. Karl Barth is the mentor of his approach and Barth was correct that there has been a need to augment theological anthropology with the understanding of the human person as a being in relation. Barth's dramatic statement, "I regard the doctrine of the analogy of being as the invention of the Antichrist," however, has left an unresolved legacy, although he may have modified this opinion later. (See Hans Urs von Balthasar,The Theology of Karl Barth, and Thomas J. White, The Analogy of Being: Invention of the Anti-Christ or Wisdom of God?) Root, in focusing on divorce, particularly emphasizes the person's being in ontological relationship to his mother and father. But in emphasizing this, one need not disparage the importance of the human person existing as a rational and free substantial being. These are the qualities that give the human person special dignity, distinct from other beings that God has created. They are part of man's being an image of God, just as much as being in relation is part of the divine image.

Root categorizes intellect and will as epistemological rather than ontological. At one point he seems to confuse substance with individualism, the power to dominate, and self-centeredness (p. 92). It is true that there was in the past a tendency to focus on the imago Dei as reflected in dominion over the earth, and not enough on man's imaging the internal relationships of the Trinity. So the focus of 20th-century theology on the analogy of relationship has been needed. However, rejecting substantial existence as the basic reality of the human person along with the essential faculties of reason and will seems like "throwing out the baby with the bath water." Of course, it has its source in the history of Protestant theology which often worries that allowing man to possess a nature of his own and to "possess" supernatural grace as an interior property conflicts with God's total freedom and gratuitous grace. However, man's substantial existence as a rational and free being is always completely dependent on God's Being and gift, and is always in an existential relationship; therefore this conflict seems unnecessary. Root suggests moving "from noun to verb" (p. 92) - the noun referring to substance and the verb to the act of relating. But maintaining a sense of substance, "that which stays the same," underlying all change, accidental qualities, and circumstances, will be important to avoid everything becoming process only, which can lead us to relativize the human person and objective truth.

Blessed John Paul II's contribution of the terms "original solitude" and "original unity" are particularly helpful here. "Original solitude" does not mean that man is meant to be by himself, but that each person has his own particular relationship with God that constitutes his dignity and special status. Man is the only creature desired for himself alone, always an end and never a means, created from the beginning in relationship with God as his image in the world. Man's restless reflection on himself and his relation to the world around him is unique among creatures and draws him toward the One who created him and toward the other that is like himself. "Original unity" expresses the relationship with the other that reveals new depths to his existence. He is called to unity with one who is like himself and different from himself, one who opens a new self-understanding. That both of these realities are essential is revealed in the adjective describing both, "original," meaning that both realities are part of our constitutive origins.

Why is this reference to both aspects of our ontological reality important? I believe it is so because all of the human persons with whom we are in relationship are imperfect. Our human relationships will always bear some element of dissatisfaction, disappointment, or failure. We need to have a solid sense of the substance of our being as grounded first of all in the eternally faithful divine Being who is also our Father and our primary origin. When a basic human relationship that structured our life dissolves beneath us, and we feel afloat on nothing, we need not give in to despair or desperation, because we always have a Father who cares for our particular life and will sustain it through all challenges.

Dr Root is going in this direction by calling on church communities to stand with the person suffering from the dissolution of their family. He provides very helpful suggestions that are practical and sensitive to the particular kinds of emotions and needs of a person in this situation. This can provide an extended Christian family to fill the hole in a person's life. However, all of us being imperfect, we can also experience disappointment or insufficiency in our communities. Only a firm understanding that over and above all we are made for God, and our being is firmly rooted within him, can provide ontological stability and peace in our life.

Nicky Rowden's words about his own religious experience after his parents divorce provide an important insight:

"It has been noted that the children of divorce frequently have problems relating to a God who is grounded in an ecclesial community, and a Church that exercises authority. We are held to be incapable of accepting authority. This is only logical, given our formative experiences. And yet God's logic transcends human logic (or "worldly wisdom," as the Gospels have it). While children whose family background is relatively secure may experience a primary relationship with God as Father, my own first relationship with God was through the Son. As a young child, after nightmares about the darkness engulfing me, I would dream that a tiny, tiny white man was placed on my tongue. Then the fear would subside. I would be safe." ("Cold War: Toward a Phenomenology of Hope" Humanum, Spring 2012.)

He also relates how Christ's suffering was a healing reality for him:

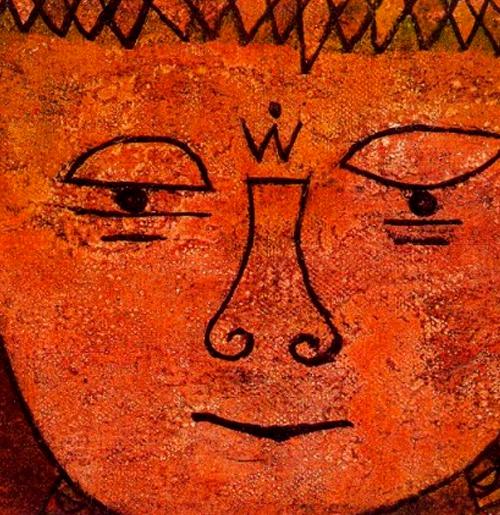

"My first and primary experience of the divine smile had to be grounded in the divine tears. I met God in his most reduced, self-effacing moment: in his defeat and death. Only there could he harrow the hell in which I felt myself to be trapped and, seizing me by the wrist as in the icon of the Resurrection in the Hagia Sophia, draw me out to the light. He had hung next to me while I was on my own uncomprehending cross, and he had told me that today I would be with him in paradise, simply because I had named him for who he is." (Op. cit.)

Rowden points out that in belonging to Christ, one does not have to accept the suffering of divorce or difficult marriages as defining one's existence. Instead, one can live in hope and give to others the love and healing received from Christ. This points to the resolution of the question of analogy of being because it is the Person of Christ who is the concrete embodiment of the analogy of being, revealing to us its true meaning. The Person Christ, in his hypostatic union of divine and human nature, is Being in its fullness and the one "for whom and in whom all is created." This Divine Person has taken on a nature that is human, thereby manifesting the essential dignity of human nature and what man is truly called to be. This reveals the analogy both of both being and relationship that exists between God and the human person. Any conflict between what man is and what God is has been resolved within the Person of Christ.

The point, therefore, is not to impose a particular philosophical structure on the pastoral ministry to children of divorce, but rather to leave an opening so that persons in this suffering have a consciousness of the deep reality of their being in God to sustain them throughout the ontological disorientation they feel from the fracturing of their family of origin. Always there is a place for them in their suffering within the heart of Christ.

Kathleen Curran Sweeney holds a Master's degree in Theological Studies from the John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family, an MA in History from the University of Washington, and a BA from Seattle University. She has published articles on pro-life topics, bioethics, theology, education, and history. She lives in Arlington, Virginia.