Helen Alvaré,

Putting Children’s Interests First in U.S. Family Law and Policy: With Power Comes Responsibility

(Cambridge University Press, 2017)).

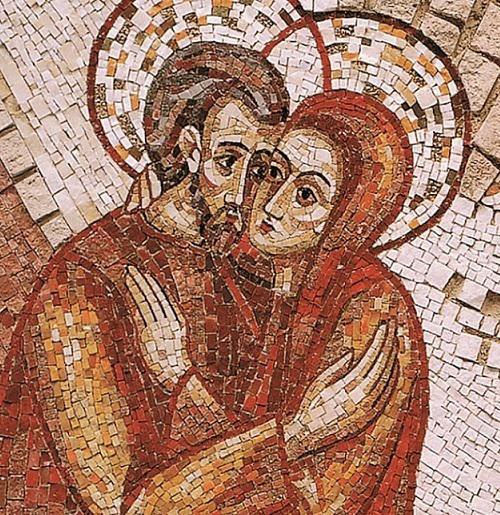

Beginning in the 1960s, the widespread availability of contraceptives resulted in a new worldview in which marriage, sex and babies were no longer intrinsically related. With this came alluring promises of freedom, fulfillment and happiness. The 50th anniversary of Humanae vitae—St. Pope Paul VI’s controversial reiteration of the Catholic Church’s condemnation of contraception—provides a fitting occasion to question the legacy of this altered understanding of human love. Specifically, what are the legal and sociological effects of the U.S. government’s promotion of this worldview through judicial decisions, laws, and executive orders?

Helen Alvaré, Professor of Law at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School, addresses these questions as they pertain to child welfare in her latest book: Putting Children’s Interests First in U.S. Family Law and Policy: With Power Comes Responsibility. Alvaré makes a compelling case that the American government’s repeated decisions to value and protect adult sexual expression, without regard to marital status, have been detrimental to children’s well-being in the United States.

The first and most substantive section of the book offers a detailed history of the U.S. government’s adoption and promotion of the “sexual expressionist position”: the “valorizing” of sexual expression while remaining silent on sex’s connection to children and the benefits of marriage for children’s welfare. Alvaré’s expertise in family law is brought to bear as she relates the history of how the Supreme Court has enshrined this stance within the context of due process rights. The process began with Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) in which the high court established a right to contraception for married couples under the guise of a supposed constitutional “right to privacy.” This right was quickly extended to single people in Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972). Both of these cases dissociated sex from both babies and marriage, and connected it to personal liberty alone. Roe v. Wade (1973) famously extended the right to privacy to abortion, further reinforcing this separation. Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992) deepened the sexual expressionist stance by connecting contraceptive sex with basic human goods: freedom, empowerment, and participation in society. Lawrence v. Texas (2003) granted a constitutional right to sexual expression outside of marriage. United States v. Windsor (2013) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) gave inherently nonprocreative sex the same legal status as procreative sex, determining that marriage is about adults’ desire for companionship and intimacy, and not at all about the cementing of the relationship of a man and a woman for the sake of the children that may come from their sexual union. Throughout these decisions and others, the court prioritized adults’ right to sexual expression over the child’s interest in having committed parents, thus communicating the unmistakable message that the paramount constitutional value is the sexual “freedom” of adults, not the welfare of children.

The Executive and Legislative branches have mirrored the high court’s stance by promoting expansive contraception programs, abortion rights, and agenda-driven sex education that is silent on marriage and its positive outcomes for children. By enacting these laws, the government has encouraged belief that it is reasonable to expect to have sex without marriage or babies. This has discouraged individuals from delaying sexual activity and undertaking the work of creating stable relationships—relationships that will allow children to thrive—before having sex. These policies have also contributed to a culture of irresponsibility in which unplanned pregnancies are blamed on “failed contraception” rather than deliberate personal choices. While, as Alvaré notes, the government cannot be assigned full responsibility for these trends, the law possesses a unique teaching authority—it enshrines and endorses a particular understanding of reality. These government-sanctioned sexual norms combined with contraceptive failure rates have led to a rise in nonmarital births. That is, births of children who were conceived, and not just born, out of wedlock) and—because a child’s family structure tends to be determined at conception—a rise in children living without married parents.

The second chapter of the book demonstrates why all of this matters. While the reasons are various and complicated, empirical data shows rather conclusively that children conceived outside of marriage are more likely to experience poverty and other economic, educational, emotional and cognitive disadvantages than children with married parents, due in large part to scarcer financial and human resources. Alvaré references a plethora of books and peer-reviewed journal articles which detail adverse effects of nonmarital parenting (such as Nobel prize-winning economist James Heckman’s work on the connection between early family environment and cognitive outcomes), and the benefits of married parenting (like Princeton scholar Sara McLanahan’s research on the connection of marriage with increased parenting time and guidance, and extended family support).

As Alvaré shows in the third chapter, the government itself has implicitly acknowledged that nonmarital births are detrimental to child welfare. This acknowledgement is evident in the government’s two-fold response to these births: (1) expansive “back door” efforts to provide material benefits to children of single-parent households, and (2) contraception programs aimed at eliminating unintended pregnancies. Alvaré provides an overview of these well-funded efforts, and evaluates their effectiveness. While lauding the government’s desire to help children, she concludes, rightly, that despite heavy investment in social welfare programs for these at-risk children (much of the 471 billion dollars that the government spends on children annually is channeled into single-parent homes), these programs simply cannot substitute for an intact family. In the words of the aforementioned Heckman: “families…are the major sources of inequality in student performance.” Regarding the second part of the government’s child welfare campaign, the federal government has invested more than two billion dollars annually in contraception programs, yet despite this the non-marital birth rate has remained high. Though it is widely available, contraception fails (as a method or due to imperfect use) and many women do not want to use it for a variety of reasons. Thus, despite the government’s extensive efforts to prevent pregnancy through contraception—and assist monetarily after children are born out of wedlock—nonmarital births persist and those children struggle to flourish in a variety of ways.

In chapter 4, Alvaré argues that the sexual expressionist position has not only failed many children, but it has hurt many adults as well, particularly women and the poor. She contends that this damage was inevitable since the sexual expressionist worldview is predicated on a false understanding of the human person. We are inherently relational and desire committed, loving relationships. Contraception encourages looser associations both between sexual partners and their children. This does not provide the authentic human love that is the deepest desire of the human heart.

While the typical government response to the problem of non-marital births is new and better contraceptives, in her final chapter Alvaré offers other proposals. Her primary recommendation is so simple that it seems like common sense, and yet upon closer examination, it constitutes a radical idea: the government needs to reverse course and reconnect sex, babies and marriage on multiple fronts. Alvaré argues that wherever the government speaks about sexual expression, it should also “explicitly articulate children’s needs for stable, marital parenting,” and encourage adult responsibility. Knowing that children’s outcomes are so profoundly shaped by adult choices about sexual expression, we must do all we can as individuals and a society to choose and support healthy relationships that are good for children. We owe it to future generations to do this. The government could aid this effort through sex education which explicitly links sex with procreation and the marital bonds that benefit children, as well as through future judicial decisions, laws and executive orders which give children’s welfare first priority.

Despite being a scholarly text,Putting Children’s Interests First in U.S. Family Law and Policy is highly readable because Alvaré has skillfully constructed it as a cohesive narrative history of the development of the sexual expressionist position in law and its socio-cultural effects. A major accomplishment of the text is Alvaré’s re-framing of the contentious contraception debate in terms of child welfare, rather than feminist empowerment. In so doing, she adopts a thesis with broad-based appeal: society should put children first and do what is best for them. And the reality is that a growing body of evidence suggests that the policies currently in place are not what is best. Therefore, we need to change course. Alvaré’s proposals offer a starting point, but her book is not intended to be a detailed policy roadmap to success. Rather it is a clarion call to think more critically about good policy for children and an effective tool for scholars, family-law advocates, policy analysts, and anyone else looking to engage people of all backgrounds in a respectful dialogue about these issues.

The logic of Humanae vitae—that marriage, sex and babies inherently “go together”—is often rejected out-of-hand as an oppressive and out-of-touch religious belief. Alvaré makes a powerful legal, sociological, and anthropological case for the validity of the logic behind this teaching, and suggests that taking it seriously makes sense if we want to put children first in family law and policy. Some may criticize the idea of reconnecting sex, babies and marriage as “turning back the clock” on human progress, and women’s progress in particular. However, as C.S. Lewis put it in Mere Christianity: “We all want progress, but if you’re on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive.”

Caitlin Dwyer is a mother of three children and an instructor at Thomas More College

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Kitchen Table Theology: Opening Up the Theology of the Body.

Caitlin Dwyer, a 2010 graduate of the John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family, is the mother of three children and a theology instructor at Thomas More University in Kentucky.