When I was nineteen, after a difficult high school experience, I made myself a promise: if the Eternal Father would give me the chance, I would try, somehow, to establish a genuine school. Mine was not. Like most Italian schools, it was secular and public. While there, I found myself drowning in the midst of an ocean, unable to find my way home. Although I had been raised a Catholic, I was in danger of losing my faith. I reasoned that the problem had to be the school; my religious beliefs and family’s traditions found little support there. Because of the absence of freedom in education, students like me were practically forced to attend a school where our ideas and religious heritage were not prioritized. Even though parents technically had the right to choose how to educate their children, at a practical level they had little choice.

The Constitution of Italy does in fact allow a free choice with regard to education: yet this provision is little known and few take advantage of it. There is the right of the parents to support, instruct and educate their children (article 30), and freedom to teach the arts and sciences (article 33). Put simply, parents may educate their children at home, following their own ideas. For me, this discovery was a light in the darkness—a means of escaping the tunnel. But there was more: since our family belonged to the “Shady Fellows,” a confraternity based on the one founded by Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati in 1924[i], we started to work together in order to seize this opportunity. We wanted to establish an actual school based on these provisions. Pope Benedict XVI also motivated us: his ideas about the “educational emergency” and the union of faith and reason confirmed our quest, but it was a couple of searing quotations from Chesterton that provided the final push: People are inundated, blinded, deafened and mentally paralyzed by a flood of vulgar and tasteless externals, leaving them no time for leisure, thought, or creation from within themselves. (G. K. Chesterton, speaking in Toronto, 1930). That same Chesterton, responding to a question about which posed the greatest danger, capitalism or socialism, also spoke with great presience of “standardization by a low standard.” We were determined to educate our children differently.

Living in this way, with no fear of affirming and exploring our identity, can only be a good thing. Small groups like ours (we consider ourselves a creative minority, to use Pope Benedict’s term) can indeed change the world as the monastic movement originally did.

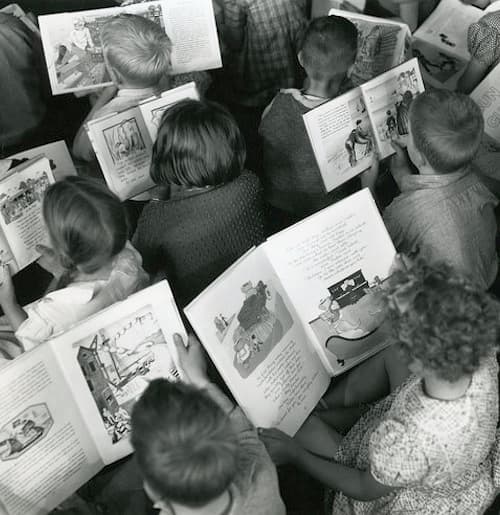

And so it was that in July 2008 a group of us in Le Marche (Italy) decided to start the Scuola Libera Gilbert Keith Chesterton (“libera” meaning free, as in non-governmental). In September of that year, lessons began for four children, including my son, Pier Giorgio. We asked the families to provide the instruction, each parent teaching a different subject. We started with a middle school, for children from eleven to thirteen years of age. Since then we have added a high school providing a classical education. There are now 28 students in the middle school, and 32 in the high school. In this way we rediscovered the fundamental right and correlative duty of families to educate their children following their own ethos. For us the Catholic faith is an indispensable perspective, one we could not renounce: it is the one that made Italy beautiful, that promoted a real culture of life, that flourished in the charity of thousands of saints.

Another joyful discovery we made during those early years were Chesterton’s distributist ideas. Our school was a clear expression of these and creating it, we reasoned, was a true work of distributism. Some years later, through Fr. Spencer Howe, a young American priest studying in Italy, we discovered our twin school, the Chesterton Academy of Edina (Minnesota), which had started around the same time as ours, inspired by the very words of GKC’s which launched ours. Now we are working together with the same aims and ideals, under the same name. Connections such as these are so important: one plus one makes not two, but a thousand times two!

The idea of family, so illuminated by Chesterton, led us to our dear friend Stratford Caldecott and his writings, through which we rediscovered the importance of the liberal arts—their power of awakening and re-enchantment. We have started to practice this ethos, in which faith and reason and a warm sense of hope prevail, for these ideas are not some strange dream, but a powerful opportunity. I can say the same thing about meeting Fr. Cassian Folsom and the monks of Norcia: in such places, these ideas are put into practice every day at the deepest level: in prayer, work, liturgy and study. I remember Stratford saying: “We are a team.” This is so true. We are grateful to find such resonance in different places, all working together for the Church.

I think that this alliance of ideas and people, of tradition and adventure, can lead to great things for the life of the Catholic Church, of families and of the whole world. Living in this way, with no fear of affirming and exploring our identity, can only be a good thing. Small groups like ours (we consider ourselves a creative minority, to use Pope Benedict’s term) can indeed change the world as the monastic movement originally did. This is a solid road for any fellowship to set out on!

[i] The Italian name for our group is the Compagnia dei Tipi Loschi de beato Pier Giorgio Frassati. It is an association of the lay faithful that has been in existence since 1993. In 2004, it was formally approved by our bishop.

Marco Sermarini is a criminal lawyer, rector and founder of Scuola Libera Gilbert Keith Chesterton, San Benedetto del Tronto, Le Marche, Italy, where he lives with his wife Federica and their five children.