In Theology of Home: Finding the Eternal in the Everyday Carrie Gress, Noelle Mering, and photographer Kim Baile set out to reclaim the home as valuable and worthy of our attention and labor. Theology of Home II: The Spiritual Act of Homemaking seeks to do something similar for the homemaker. At a time of the fragmentation and dissolving of the home in favor of the state, this task is not only important, but difficult. Try for a moment to define home. It’s hard. Home strikes me as akin to love, truth, and being—words that are so close to our original experience of the world and ourselves that they very nearly elude definition. And, indeed, in such cases a definition is only a paltry attempt to articulate something known in a deep way, something at the root of all our knowing. But it is also fair to ask if a definition of home is possible? Think of all the variety of homes. Not only does our age at once disparage home (the denigration of stay-at-home moms) and glorify it (the myriad of home improvement shows), it is also very much at risk of losing any sense of the universal character of home, dissolving its meaning into mere intentionality.

The authors of the two books, Carrie Gress and Noelle Mering, are wives and mothers as well as writers who have contributed numerous articles and books. Both are fellows at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C. and Gress is also a scholar at the Insitute for Human Ecology at the Catholic University of America. The now three volumes of Theology of Home are part of an effort to support homemakers in their service to their familes and the world. One can only welcome an attempt to refocus our attention on the home and homemaking in an essential manner from such accomplished Catholic women. The books are peppered with beautiful reflections, quotes, and images. They offer much to delight.

The two Theology of Home books are not written around a thesis so much as a goal, to offer

a simple guide to help reorient all of us toward our true home, allowing us to think purposefully about how to make our homes on earth better equipped to get all those living in them to the Father’s house. It’s an effort to help us rethink the honor that accompanies being a homemaker, to provide those we love with safety, nourishment, affection, love, creativity, comfort, and freedom.

The authors refer to the first book as a tour of the home and as a journey. Likewise, the second introduces the reader to a variety of women and reflections on the characteristics of women as they intersect with life in a home. The book moves from topic to topic as child on a beach might move from shell to shell. An argument is not being built so much as a series of precious treasures held up and admired.

Particularly outstanding in the second volume are the many portraits of women that show a variety of experience and reveal the many ways women bring their genius to bear in the world through their fidelity to the demands of the life of a home.

We must begin with the home as a universal, transient human thing. We must find in it a goodness and a beauty that is too good to be a passing flash in a broken world, a good worth offering up our suffering for. Full of gratitude, we must seek out the source of this good.

The title of the work comes from the authors’ beautiful insight that the home is a privileged place of evangelization. People who may have no inclination or desire to enter a church will find themselves in homes that are ordered by Christian love, which might in turn lead them to seek the origin of the beauty experienced in such homes. Nonetheless, the title is unfortunate. The books aren’t theological. They are instead cashing in on a trend of using “Theology of...” without doing the hard work of justifying what “the study of God of the home” could mean (not to mention clarifying the use of the genitive). I take it to mean that the order of a Christian home is revelatory in some way of God’s love.

A justification of the title would in fact have forced the authors to think more carefully and in a sustained fashion about the human reality of the home. But a clear definition of home is not to be found, which means the book lacks a captain idea around which to marshal its many insights. The authors refer at times to physical homes, but often equivocate on the term, referring to the Church, heaven, a prison cell, a spouse, and a temporary quarantine shelter all as homes. Moreover, the general pattern in any chapter is to affirm something that generally has to do with the home, and then move rather quickly to the spiritual meaning of the topic. Hence the topic of entering an actual home quickly moves to the heavenly Father’s welcoming of us in his home, with its many rooms. And we are told that if we don’t love and seek heaven above all else, a love for our homes will be meaningless. This may be true, but it isn’t particularly helpful in recovering the meaning and value of home. This confusion seems to dog the book, the authors both trying to affirm home and relativize its transient value to eternal things. This leads at times to whole chapters in which the home is hardly mentioned and the reader is not even sure if the chapter is about the home. As an example, in the chapter about light, the authors begin by discussing how humans are drawn to and gather around light, and then go on to discuss what the symbol of light means to people (joy, weightlessness). The chapter continues to speak about Christ as the light, light in the liturgical calendar, illumination of the intellect, light as a metaphor for God and light transforming Romanesque architecture into Gothic. A special section is given over to the moon as an image of Our Lady, followed by a final meditation on the darkness of the world and Christ as the inextinguishable light who announces the light of heaven. All of these are good reflections, and more or less interesting according to taste. However, by the end of the chapter I still do not understand what light has to do with my home or, more to the point, the nature of home. Can all this be found in the home? I believe so, but the authors have certainly not shown how the home speaks to these realities.

I find the problem significant. I am a homemaker who spends her days in the home, and I know both the tedium of housewifery and its profound joys. I know what it means to feel like I am doing some of the most significant and most disregarded work necessary for culture to thrive, to feel that I am outside of the “real work” of offices and banks and universities. In addition, we live in a time when totalitarianism thrives at the expense of a robust homelife, and the light by which we recognize it often comes from the home. But unless we understand what a home is, it will not be clear to us why the lights by which a child sees the world could never be separated from being welcomed into a home. A home has everything to do with intellectual light, for example, but unfortunately the authors do not unpack this for us.

Gress and Mering are clearly concerned with what they call a “loss of the sense of the eternal.” The conviction that comes across in their books is that if we can rekindle a love and desire for the eternal, we can return to the home with renewed energy. Their method to rediscover the eternal in the mundane seems to be by way of reflecting upon the content of our faith as motivation to love and cherish our homes. But it won’t do. It isn’t enough. Such a method can be used to help one be a garbage man or a banker equally; it is the old “offer it up” version of Christian life. We must begin with the home as a universal, transient human thing. We must find in it a goodness and a beauty that is too good to be a passing flash in a broken world, a good worth offering up our suffering for. Full of gratitude, we must seek out the source of this good. We must ask if there is One who can save the goodness found uniquely in the home from being carried away by the brutal movements of history.

What can be said about the universal nature of home and its particular goodness? Mering and Gress offer the beginnings of an answer when they quote G.K. Chesterton:

The place where babies are born, where men die, where the drama of mortal life is acted, is not an office or a shop or a bureau. It is something much smaller in size and much larger in scope. And nobody would be such a fool as to pretend that it is the only place where people should work or even the only place where women should work; it has a character of unity and universality that is not found in any of the fragmentary experiences of the division of labor.

Unfortunately, the authors don’t press into this quote. Historically, home was where people were born, lived, worked, and died. It contained the whole drama of life. And despite the reassigning of birth and death to institutions and the advent of the hated commute, it remains the place where all the questions of life’s drama are given space. Home is where we give ourselves to others and receive others, where the deepest betrayals are felt, where all our yearnings and needs are known. Home is also the place where children are welcomed and grow. It is the primary space in which the meaning of human life is communicated to a child, and it is the safe place in which a child learns to speak. It may be that a child spends seven hours a day at school, and yet it is still the hours at home that allow a child to take in new experiences, to understand them, to question and wonder, and to disagree without fear of rejection. It is all too well-known that a child who has a chaotic home will have a much harder time learning in school, and I suggest it is precisely because the contemplative character of the home is essential for a child to receive an education by allowing space to reflect, understand, and articulate experience.

This contemplative character of a home is directly tied to its character of love. Home bears an order of love. A home begins with a marriage, a bond that is the unconditional giving and taking in love. The welcoming of children is the sign of that giving and taking, receiving and bearing. This love is the atmosphere of the home, prior to and more significant than any other effort a mother or father puts into their home. You may want a musical home, a prayerful home, a studious home, or a light-hearted and merry home, but prior to all those efforts is the reality that a home was made by the acceptance to be determined by love and the task to make a space for that love to be lived.

The phrase “a broken home” (most certainly soon to be condemned as an archaic, repressive way of speaking, but nevertheless testifying clearly to the experience of many children who live it) has always to do with the breakdown of love that initiated the building and making of a home. A child can disagree freely (and so become a “free thinker”) first at home because he was freely welcomed. One shouldn’t have to earn a place in a home, and that is why at home you can be sick, you can be crude, you can test all the boundaries, you can cry and yell, the plates can be thrown, and forgiveness is possible. In short, because a home is crafted in love and ordered by love, it can be a mess.

In passing, this point leads to another criticism of the series: the pictures of home life depicted in the book are staged and, well, just too beautiful. They show many homes worthy of Instagram, but they don’t show home life. They are beautiful until you find yourself thinking that if you were doing it right you would have a large spacious home like that, free from mess.

The home is that which binds us to a social order. It provides a reason to work, to suffer in one’s labors. It is also the place in which material goods are given a place and order. Think for a moment: furniture is made, cloth woven, money invested, oil refined, cars manufactured, the machines of war produced all for the sake of homes, that a mother may comb her daughter’s hair in peace. I do not mean to suggest that all of human work is not rife with a myriad of intentions good and bad. But if you were to eradicate the home from a society, there simply would be no reason to continue in all these things, the activity would appear grotesque, inhumane, dystopian.

Interestingly, in most dystopian stories the home has disappeared. Home gives the human person a place from which to take his stand in the world. And in this sense, as Chesterton noted, the home is anarchic. Without it, there would be no freedom to stand against unjust governments. And it is no secret that any government seeking to control its citizens will attempt to shift the center of life away from the home to other government-controlled institutions. The weaker the bonds of the home, the more susceptible we are to being determined by the will of something other than our own, that is, the more susceptible we are to slavery. The order of relations in the home, an order of love, are an order more fundamental than any social order. The attempt to put the family home in service to a government, or to override its natural authority in the life of a community, is ultimately to lead to the dissolution of that community. It can’t be any other way, even if for a time the state thrives in its tyranny; to obliterate the home is to lose the meaning of the whole and condemn it to death.

Thus, the home is a particular place, in a particular time, formed by the gratuitous order of familial bonds for the sake of the flourishing of those persons. In the home, all of the material order is taken up both binding the home to a larger community and correcting the excesses of that community. And the good that is found in the home remains vulnerable to the tyranny of larger institutions and yet powerfully fundamental to the flourishing of a society. At the same time, every home is as transient as the mortal lives of those who live in it, and thus the immeasurable good found in a home, that promises so much, is constantly threatened by the weakness of those who live in the home, by the accidents of history, and by forces that conspire against it. The goodness of home life intimates the promise of eternal goodness and in doing so reveals our need for an eternal salvation.

***

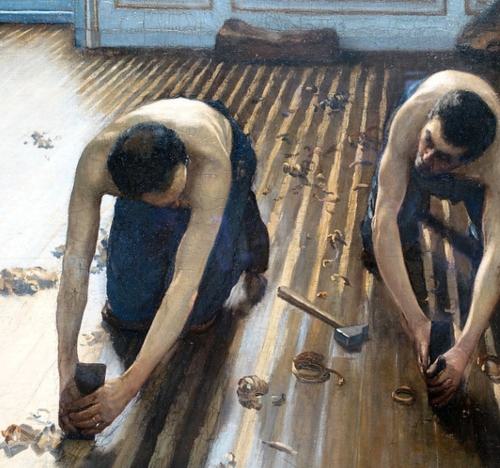

Finally, I find it unfortunate that Gress and Mering seldom pull from literature and art to think about the home. Their preferred sources seeming to be saints, theologians, and essayists— altogether too cerebral a crowd to offer a starting point for this earthbound thing. Paintings and literature and poetry could offer a starting point for a reflection on the home that helps us to catch sight of the eternal in the concrete realities of the home. For example, the first time I saw Gustave Caillebotte’s painting The Floor Scrapers, I was struck by the clear word it speaks about the infinite value of the home. The painting is of three men laboriously stripping a wooden floor in an elegant Parisian room. The poor, shirtless laborers, working on their hands and knees, contrast sharply with the opulence of the gilded room. Their strong, vulnerable bodies form a loose V, the very tip of which are the outstretched arms of the middle laborer, and upon his finger glints a wedding band. That glint changes the sense of the entire painting. Here is a poor man working hard in a powerful man’s palace, and yet he has pledged himself to a woman who has received him wholly, and to her he will go at the end of the day. His home shelters him from all the harshness the world might bear toward him in his poverty. He hasn’t the wealth of this room, but he has the wealth of a home and the love that has risked to build a home with another and for others. There he can speak his mind as a king, offer hospitality to a friend and shelter to his children. Moreover, the entire sense of his labor changes. His work provides for his home and his home binds him to the social act of work. He is, in fact, not primarily a laborer, but a husband, a member of a home. He has built his life around this relation, and to this relation above all else he has given his allegiance. He has a reason to labor hard but, equally, he has a reason to revolt. And more important, he has a reason to pray. You cannot help but see both the goodness of his pledge and its fragility. The promise of forever needs a greater power to secure it. The wedding band reveals the depths of human desire and meaning present in a husband’s labor. The glint of the ring opens up a window to eternal questions that would not have arisen had Caillebotte left his hand bare, that is, had left him a homeless laborer.