The following is an excerpt from Josef Pieper's Tradition: Concept and Claim (trans. E. Christian Kopff, South Bend: St. Augustine's Press, 2010: 66‒68), introduced by Mark Milosch.

In Tradition: Concept and Claim, originally published in 1970 in German, Josef Pieper explores the elements of tradition. He ranges through classical and Christian antiquity to argue that tradition, in its most proper sense, refers not to cultural traditions nor even religious customs but to the “unimpeachable” core of a sacred tradition—“TRADITION within tradition.” Pieper’s conclusion marks the gulf between him and his contemporaries: we philosophize truly only when we stand within a sacred tradition and participate in it as a “believing hearer,” so that, like Plato and Aquinas, “on the one hand, the independence of both [reason and tradition] remains clearly preserved, while on the other hand, on the basis of reciprocal corroboration, challenge, and perhaps even disturbance there arises a new and richer harmony... the existential impetus, authenticity, depth, and (so to speak) stoutheartedness of the act of philosophizing is dependent on whether or not this contrapuntal relationship to the sacred tradition is realized or not.” Pieper closes his essay with mordant words on the modern will to break utterly with tradition—a disaster for philosophy and for humanity:

The exclusion of the “sacred tradition” from the practice of philosophizing can occur in two ways. The first is by the destruction of its content and its replacement by a kind of anti-tradition. A perfect example of this is Jean-Paul Sartre, who bases his philosophy explicitly on the dogma of the nonexistence of God. From a purely formal point of view, Sartre has preserved completely the contrapuntal ordering of the known to the believed. I am convinced that this is the reason for the perplexing existential relevance of Sartre’s philosophizing. It is a clear example of that “inclusion” of fundamental positions which concern the whole of reality and must be assumed without critical examination as the presuppositions for rational thought. My one reservation is that this purely negative dogmatics is admittedly proclaiming its opposition to all sacred tradition.

There is, however, another, even more effective way of silencing the tradita in the field of philosophy: by denying not the content, but rather the formal structure of the contrapuntal ordering itself. According to the program of “Scientific Philosophy,” for instance, philosophers are supposed simply to stop reflecting on the whole of world and reality from any possible aspect. Instead, they are supposed to limit themselves, like physicists, to the questions of their academic specialty, and then to solve them with verifiable results. Of course, in such academic fields the occasion for an appeal to tradition, whether sacred or profane, arises just as little as it does in physics. At any rate, philosophy—still called by this name—turns unavoidably into a business that can only be pursued by specialists and is in fact of no interest to anybody else. The place that belongs to philosophy and the philosophizer in the whole of existence remains empty.

[R]eal unity among human beings has its roots in nothing else but the common possession of tradition in the strict sense—I mean, our sharing in common the sacred tradition that goes back to God’s words.

“Empty” is also the word used by two important philosophical critics of our time to describe the intellectual condition created by such a consciously tradition-less philosophy. (They are philosophically very far apart and certainly used the word independently of one another.) One is Karl Jaspers, who with his eye on a widely influential figure of contemporary philosophy says that the contents of the “Great Tradition,” without which philosophy must inevitably die out and disappear, have been abandoned, and that the result is “an increasingly empty seriousness.” I have quoted several times Viacheslav Ivanov, the “Western Russian,” scholar of myth, humanist, and philosopher. Confronted by the liberal historian, who is hysterically rejoicing in the good fortune of bathing in the stream of the river Lethe in order to wash away every memory of religion, philosophy, and poetry and then walk to the shore as naked as the first man, he answers with the decisive judgment: “Freedom achieved by forgetting is empty.”

Another aspect of the catastrophe that threatens the intellectual community of mankind because of the loss of knowledge of sacred tradition was expressed by one of the last essays written by Gerhard Krüger before the silence that he has maintained for many years now. The essay contains the frightening sentence: “The only reason we are still alive is our inconsistency in not having actually silenced all tradition. . . . We are facing the radical impossibility of a meaningful common existence, although no one can imagine what this end would be like.” Anyone who is inclined to consider this statement as an excessively gloomy cry from a modern-day Cassandra should reflect that we are dealing with a very precise assertion, which has nothing to do with the literary genre of uncivil criticism of the present or a vague philosophy of decadence. Krüger is alluding, with complete seriousness, to the unifying power of tradition. He is pointing out that the decisive unity of the human race cannot be based on or guaranteed by realizing a political “One World” or any kind of unanimity of “cultural wills,” no, not by a shared respect before art and science, not by the technical possibilities of communication throughout the planet earth, not by a universal world language, whether it be English or Esperanto or Chinese, not even by international organizations for athletic competition. Rather, real unity among human beings has its roots in nothing else but the common possession of tradition in the strict sense—I mean, our sharing in common the sacred tradition that goes back to God’s words.

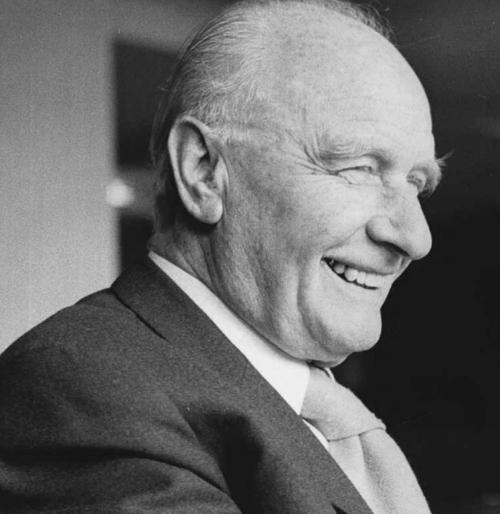

Josef Pieper (1904‒1997) was one of the pre-eminent Thomist philosophers of the 20th century.