I have a black and white photograph taken in 1967 that I found among my grandmother’s things after she died. In the foreground, my grandmother sits on a blanket, smiling self-consciously for the camera. To her left my brother stands in a seven-year-old boy’s macho pose with hands on hips, his smooth, hairless chest thrust out, with a half-grin, half-grimace on his face because he is looking directly into the sun. I cannot specifically remember this day but I recall Sunday afternoons like it—those rare, warm days in August when we piled into my mother’s second-hand Morris Minor and drove up from the crowded suburbs of Manchester into the hills of Derbyshire.

Behind my brother and grandmother, set back a little way and sitting on the brow of a hill overlooking a body of water, are my grandfather and me. We are both facing away from the camera. He is leaning on one arm, semi-reclining; I sit close up against his chest, the top of my head appearing just above his shoulder. We are looking at the lake beneath us as it stretches away into the distance, a sheet of shimmering metal overtopped by the cloudless, endless sky of childhood. I hear skylarks swooping and twittering among the grasses and the indolent basso continuo of bees nuzzling clover. The heather flowers purple and white at my feet as the daisies modestly offer their pink-tipped centers to the sun. My fingers are yellowed with buttercup pollen, fingernails greened with their juicy stems as I fashion a Lord Mayor’s chain of gold to hang around my grandfather’s neck. In the pockets of my shorts are the stones I have collected, mica-veined granite, blue-green slate, and snail shells—humble, exquisite, and infinitely fragile, a hoard of happiness to be set out on my windowsill before I go to bed that night.

I am resting now in my grandfather’s embrace, lulled by the tremor of his heart, unaware that a more lasting record is being taken, a thumbnail of celluloid that will survive for forty years, a perfect snapshot of my childhood after my treasures have long been broken, lost, or discarded.

My mother, brother and I lived with my grandparents for eight years after my own father abandoned us when I was a baby. Until he retired when I was five, my grandfather was a typesetter at one of the major Manchester newspapers and was gone during the day. Each evening I would wait at the gate for him to return, running down the street to greet him when he crossed the road, a tall man with a long stride which he accommodated to my three-year-old legs as we walked back to the house, hand in hand.

Parting from my grandfather five years later was my first experience of the hunger I have since come to recognize as loss.

Until then, I remember a time spent among growing things, things wet and loamy, green-tasting, new, my infant senses moving like feelers over the surface of a pristine world, hesitantly and full of wonder. My earliest memories are of my grandfather digging in the allotment he rented from the township, the crunch of the spade biting into the ground, his foot on the blade, bearing down; the dry sift of bone meal scooped from burlap sacks, dust lazy in sunlight. And then, at the end of the day, the trundle and bump of the wheelbarrow over pavement when I was too tired to walk home, my grandfather’s face the sky that bounded the horizon of my childhood.

In his greenhouse he grew tomatoes, fragile shoots he planted in humus, then puddled and pressed down, his fingers—nicotine-stained and rimed with dirt—moving delicately and deliberately. Those same hands smoothed the covers up to my chin each night, planting me in a bed of warmth and darkness, his love for me the water that fed my roots, the heat that drew me upwards, all five-foot, seven-inches of me, a suddenly gangly seventh grader.

The taste and scent of baby tomatoes picked from the vine is, for me, the taste of paradise long foregone. Store-bought tomatoes are the ultimate postlapsarian tease—perfectly round, polished to a jeweled sheen, but scentless, tasteless, and inclined to soften. My grandfather used to pray before each meal: “For what we are about to receive, Lord, make us truly thankful.” But like Adam and Eve before the fall, I could not be thankful for what I did not know would end. I did not dream of famine or drought, bad husbandry, disease, blight, waste, or mediocrity. I did not think the crops could fail.

Food was the outward and visible sign of my grandfather’s love, and I received it as matter-of-factly as a lifelong communicant receives the host. The high priest of my childhood, his robes smelled of earth and cigarettes, the tweed of his jackets scratchy against my cheek. He taught me World War II songs, checkers, the card game “Patience,” and how to pray. At meals I sat at his right hand and ate blithely, without conscious gratitude but with careless and innocent joy. My first joke was: “Gramp, how come your string beans are all string and no bean?”

Once a year, on Father’s Day, I would walk down the street to the sweet shop on the corner and buy a pound of my grandfather’s favorite candies. Sugar-encrusted, fruit-flavored jellies called jujubes, they tumbled from the scoop in a pulse of color, bulging the white paper bag that I carried home under my coat as carefully and furtively as if they were the Crown Jewels.

On Fridays—fish days in our pre-Vatican II Catholic household—he and I would walk to the local fish and chip shop. On the way there, I would hold his hand but on the way back I would cradle the hot newspaper bundle under my sweater to keep the food warm for the table. My grandmother would complain that the stink of salt and vinegar was impossible to remove from my clothes, but to me it was the smell of happiness—sharp, pervasive, and, I thought, indelible.

I was seven when my grandfather had his first stroke and was bedridden for a time. I stopped coming to table and, instead, hid in the laundry basket in his bedroom, fasting and keeping vigil until I was discovered and hauled out.

At about the same time, I began to have episodes of vomiting, and foods that I had previously eaten without complaint suddenly nauseated me. For the first time, I became aware of the sounds my stomach made after eating and learned that this was called digestion, that the gurgling was the dirty water going down the drain after a bath, that my mouth was the hole in the tub and my body a series of pipes.

Without my grandfather’s presence, food was no longer a miracle winging down in the beak of a raven or an angel appearing to Ezekiel saying, “Eat. Drink.” Food had become a thing, a dead weight in the pit of my stomach, the heft of nothingness.

When we moved from my grandparents’ house to our own home, the gulf between sign and signifier grew, the object becoming more lifeless, more inert. As if to prove it, I began to consume the inedible. In the course of a single term I ate the leather strap of the purse that I kept my lunch money in at school, the texture of the strap paradoxical in its inner toughness and the outer slipperiness of the leather softened by saliva. I ate the wood of pencils down to the nub and consumed paper tissues pellet by pellet, then started on the inside of my cheek, self-cannibalizing until I bled, oddly comforted that my food of choice was always available, something of my own and not dependent on the largesse of others.

Cut adrift, I was already cutting myself off. Later, I would call such solipsism independence.

My mother worked days as well as nights, and my brother and I took turns preparing the evening meal by peeling and boiling vegetables while my mother grilled the meat. I remember my mother’s fatigue and hopelessness leaching into the silence like carbon monoxide—odorless and colorless.

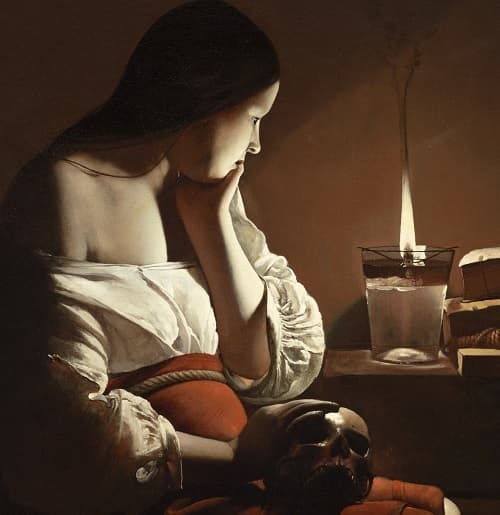

In my teens my grandfather suffered a series of increasingly debilitating strokes, and every day after school I would cycle to my grandparents’ house to visit him. I would read his favorite Psalm aloud to him—“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death....” But when I looked at his garden, now infested with weeds, his greenhouse empty and opaque like a closed eye, his allotment sold off, all things passing away, I did not believe in a Good Shepherd.

At mass I would help him to Communion, his arm brittle and sticklike beneath my hand, his shoulders rounded, stooped, the nicks and cuts on his neck telling me that his hands shook too much for shaving. He insisted on fasting for twelve hours before taking the host, even though his illness made him exempt from such mortification and the fast had been reduced to one hour after Vatican II. Only when he was dying would he consent to allow the priest to bring him the host at home. “McEntee stubbornness,” my grandmother said, the Irish cognomen carrying the full weight of her Anglo-Saxon disapproval, as if it were a synonym for mule.

At the very end of his life, he became unable to feed himself, and my grandmother became enraged by his inability to swallow and the way the food dribbled down his chin. I would feed him, spoon by careful spoon, and talk of my day and my studies and the books we loved as if words could stanch his humiliation and shame.

I was out of the country when he died. When I returned, my grandmother had removed every trace of him from the house. When I opened the closet, only the memory of his scent remained, like the barely heard whisper of my name in the dark.

I too began to fast, not with the holy asceticism of my grandfather preparing to receive the bread of life, but with the vaunting non serviam of the apostate. Instead of food, I digested rage; instead of flesh, I glutted on words; instead of God, Nietzsche. His Triumph of the Will was my manifesto, the credo of a believer in nothing, the faithful communicant of the sacrament of antimatter.

Or that is what I told myself. In reality I was abandoning God as he had abandoned me—starvation as preemptive-strike theology—in order to avoid saying the unthinkable: Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?

From the depths of her body’s malnutrition and her soul’s plenitude, Simone Weil warned: “The danger is not lest the soul should doubt whether there is bread, but lest, by a lie, it should persuade itself it is not hungry.”

When I lost my appetite for bread, I stopped going to mass. But my hunger did not diminish; it grew. I began to mistake the physical effects of starvation for spiritual purity: eating became a sin; starvation, a virtue. My body appeared gross and bestial and its incessant clamor tormented me, but unlike the desert fathers or the great saints who denied themselves in order to affirm the goodness of what they denied, my fasting nullified the world. Simone Weil said: “All sins are attempts to fill voids.”

I was a suicide posing as a hunger-striker.

My teens were spent in an orgy of self-destruction and the annihilation of my mother’s happiness. I refused food but submitted my body to the more insidious fruits of drugs and the dark sexual tutelage of a much older man until, one night, traveling on a bus between Paris and Calais, I saw in my hollowed and ravaged reflection the darkness I had become, with pinpoints of light showing randomly and seldom. It was an epiphany of sorts.

At Oxford University I returned to the church of my childhood, where I encountered my grandfather in the curve of an old woman’s back as she knelt at prayer and in the knock of knuckle on breastbone, the murmur “Mea culpa....” In the breaking of bread, that audible crack when the host yields to the force of human flesh, I heard the breaking of my heart and saw it lifted up in the service of something other than unredeemable loss.

When I became a mother I was able to revel in abundance, cradling my unborn children the way I had clasped the fish and chips beneath my sweater—my belly warm and bulky, the heat of it alive and life-giving, the mystery of me and of another. Then I would remember what I had forgotten, that the flesh is the outward sign of inner grace.

“This is my body.”

Watching my toddlers in their highchairs taught me that food is miraculous, its myriad colors and shapes, its glorious textures, an invitation to play. Squishing peas or squeezing fistfuls of mashed potatoes, my children were Adams and Eves discovering the wonder of creation for the first time, reaffirming the gift of this world and offering it back. Called to tend the vigorous growth of their bodies, I adored every crease, concavity, and roundness, observing the dewy sheen of lips parted in sleep, caressing the cool pearlescent flesh faintly tinged with blood. With their eyes, they drank the world entire and did not disdain to bring it to their mouths and taste. Hands that clutched, held, kneaded, and stroked, also blessed, and as I obeyed their infant commands to name the things of this world, the world was made holy.

Now, a low table and two chairs sit beneath a plum tree. On the table are a pot with purple flowers, a verdigris statue of a sparrow. There is a bench under the apple tree and a dripping stone birdbath. In my house, leaves and bits of grass litter the floor as if the garden had moved indoors. On the windowsill sit gifts my children have given me over the years: shells, rocks, pinecones, treasures to replace the ones I lost from that summer’s afternoon long ago. Now all but one of my children are grown and the three oldest have moved out of the house. I tend my flowers, herbs, and tomatoes and find myself returned to the place I first knew, where the boundary between those who sow and those who reap forever blurs. At dusk the house rides like a light-bedizened ship on a darkening sea waiting, like my heart, for my children to return.

I would like to say that my hunger has been satisfied, but this is not the case. When I am lonely, exhausted, and discouraged, the temptation to deny returns. I still find it difficult to go to restaurants, to eat in front of strangers. Often when I attend mass and file slowly up the aisle to Communion, I feel like a gate-crasher at the heavenly banquet and take the host like a beggar pocketing a dinner roll. I tell myself that if I were good enough, I would live on the Eucharist alone and it would not burn my conscience or dissolve like air. If I were good enough, I would whisper: “Father, I am hungry; for the Love of God give this soul her food....” But I am not a holy anorexic like Saint Catherine of Siena. I am just a child greedy for love.

Since my self-expulsion from Eden when I was fifteen, I have sought the voice of my grandfather calling me back to Communion. I know now what I knew in the paradise of my childhood when he and I walked together in the cool of the evening, when we sat looking at the still-life of an idyllic summer afternoon long ago—that all my life I have been seeking what I had already found.

Suzanne M. Wolfe is an award-winning novelist who grew up in the UK but now lives in the Pacific Northwest. Her latest novel, A Murder by Any Name(Crooked Lane Books, 2018), is the first in an Elizabethan spy mystery series. The second in the series, The Course of All Treasons, is forthcoming in December, 2019.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Last Days: Caring for the Terminally Ill