In the final days of her life, my elderly mother, suffering from the pains of age and mental confusion, grew very tired of life and wanted to die. As she lived in Canada, she was able to ask for a doctor to come and administer the drugs that would, as she said, “put her to sleep.” Cheating death by weeks, perhaps days, the doctor’s role in euthanasia appears at first glance to be compassionate and caring. It is terrible to see someone suffer from the pains that accompany the approach of death.

The law which entitles doctors to kill patients at their request in Canada is called MAID (Medical Assistance in Dying). It has become quite acceptable to many Canadians, churchgoers and non-churchgoers alike. In her retirement home, as I would learn, it had become a not uncommon way to die. This is a remarkable cultural change which seemingly happened overnight. Why should a generation of people—many of whom considered themselves Christians, and had attended a church all their lives just like my mother—accept this? One answer is that if pressure is placed upon a suffering person to choose assisted suicide they may submit because they are weak and suggestible. But it cannot be denied that for generations Christian churches have failed, for various reasons, to defend doctrines of the faith and so to accommodate church mores to society. Assisted suicide is another example of this tendency.

The teaching of historical, catholic, Christianity (East and West) is that suicide is a sin, all the while acknowledging that God in his omniscience is merciful to people who commit violence against themselves because of mental illness. Yet insofar as it is an act of violence taken against oneself, suicide has been considered an act against the natural order. But legalized euthanasia raises a new dilemma for moral reasoning: is a drug administered by a physician at the behest of the patient to end his or her life, when allowed by law, or encouraged by a doctor, likewise a sin? Furthermore, since by law the procedure is administered to someone quite sound in mind, and each candidate for MAID must pass a test for mental competence, is assisted suicide a legitimate moral choice? Should it be acceptable as a medical procedure, under conditions of bodily pain and the accompanying depression, if the person is elderly, deemed mentally competent, and close to death? Is society at a point where it is ready to deny God’s sovereignty over life and death, from the beginning to end of life for the sake of allowing people to die just a little earlier than they otherwise would? The answer is unfortunately, yes.

Assisted suicide is a Trojan Horse, a false gift. It looks like compassion, but from the standpoint of Catholicity, it robs the elderly of their integrity.

We learned that my mother had scheduled this “procedure” only three days before it was to take place. She had been in some pain, although the pain was controllable. But she was elderly, and she knew others in her home had taken this step, so she had no qualms.

By the grace of God, we were, however, able to convince my mother to change her mind. That is a longer story than I can tell here, but she was moved to a hospice for care and died shortly afterwards. I say by the grace of God because having been determined mentally competent, we could not interfere even with power of attorney. On top of that, the euthanasia doctor was aggressive in coming between my mother and her family. I wonder if that is normal, or if we had a particularly aggressive doctor to deal with, but in our case, it made the situation even more difficult.

I am not the only person I know who has been surprised at the speed with which euthanasia has become accepted in Canada. The aging generation, my parents’ generation, are the most likely to take advantage of this law, according to statistics. One might argue that the changing moral compass of society over past decades has undermined their resistance. Yet it is still surprising because I do not believe that my mother, even ten years ago, would have countenanced such a step. This is a fact which we must face.

It means that the few Christians who still hold to the overriding goodness of God in life and death find themselves in opposition to doctors and possibly other family members when dealing with a family member who has chosen MAID. It is a difficult situation because in a world in which there is no “sin” except lack of compassion, a Christian who calls suicide a sin, according to Church teaching, has no compassion. This is highly confusing for Christians who view themselves as compassionate! In Canada, the Roman Catholic Church, a handful of Protestant denominations, and a few Rabbis have publicly opposed MAID. Yet there is no solid Christian opposition, and some ministers condone the MAID deaths and bless the procedure.

How does a Catholic Christian respond to this situation? One theological response might be this: in light of Christ’s promise of a resurrected and eternal life, in a new heaven and a new earth, where body and soul are reunited, we can have certain knowledge that each individual is unique, body and soul. Suicide is an act of will by the soul against the body; it is a sundering of that union. It is an act which implies that the body is the enemy of the soul. Technically speaking, this falls into the heresy of Gnosticism.

A second response might be this: human beings are rational, which means that their souls are composed of intellect and will. They have, as scholastic theologians said, a “rational will” and are therefore moral beings. In the distant past, in ancient Greece, Plato and Aristotle had first argued that men are rational animals because they can choose to act or not to act, they deliberate about their acts, and thus may be held responsible for the wisdom or foolishness of their actions. To that ancient teaching Christians, knowing that God made us in His image, added that the reasoning power within each person is the image of God in us. For that reason, as St. Paul wrote in Romans 1, even the Gentiles can be held responsible for what they do. Justice and morality find their origin in God, we are created to act justly, we have been given the power to do so, and added to that, there is the promise of a resurrected body and soul after death. The decisions which we make in this world are permanent. God will hold us accountable for being just to ourselves and to others through eternity.

The logic of this teaching is found in that great poetical treatment of the afterlife, the Divine Comedy, composed by Dante Alighieri in the early 14th century. There are three canticles or distinct poems about Hell, Purgatory and the heavenly Paradise. The Divine Comedy is not only a work of poetry, but of philosophy and theology. The entirety is about the sovereignty of God over all creation, and shows the depth of his reading of the greatest of all theologians, St. Augustine, St. Bonaventure, and St. Thomas Aquinas. But it is also a great allegory of a soul’s choices, and the happiness and unhappiness which results from these choices. Yet, overall, the Divine Comedy is about the inner light and joy awaiting souls who know and love God. The third of the canticles, the Paradiso, is an unforgettable depiction of the saints and angels in heaven, an allegory of the redeemed community, complete in love, complete in the knowledge of truth, moved as one by the love of God. It is this final canticle that helps the reader comprehend fully who God is, as ruler over all creation.

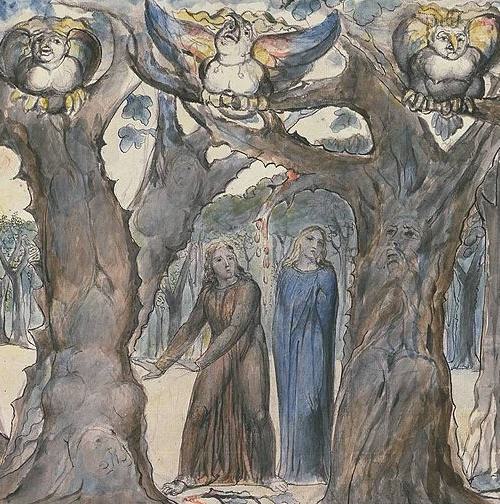

In the Inferno, or Hell, however, Dante depicts the fate of those who rejected God out of hatred for his creation, for other human beings, and of course hatred of themselves. Dante placed the souls of the suicides in the general category of those who committed sins of violence. Their punishment is to be divided forever, body and soul; the punishment is an image of the act itself.

Following the seventh book of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Dante divides the Inferno

into three categories: sins of incontinence, sins of violence, and sins of distorted thinking (fraud or treachery). The sin of fraud is the worst because to commit fraud is to use the mind, the highest faculty in the human soul, to pervert and undermine the reasoning of someone else. Dante thus placed the sins of fraud below those of violence. Sins of violence are brutish, because they lack reason—violence is the act of animals who do not know better. But to persuade someone else to commit suicide in Dante’s scheme is to deceive them about their own good. There is a twofold aspect to fraud. First, to convince someone that evil is “good”, to trick someone into doing something sinful, that they themselves should know is bad, is a harm. It is harm to a neighbor. The person who persuades another to do evil, however, in that act of treachery, harms himself as well, by denying God’s sovereign order over himself. Thus there are two harms; the fraudster who harms himself by acting as a spiritual thief, taking the place of God in calling what is evil good, and his victim, the person he robs of integrity by counseling wickedness.

Let me give an example. In a famous and very moving passage in the Inferno, Dante placed the Greek hero Ulysses among the fraudulent (Inferno, XXVI), because Ulysses counseled the Greeks to trick the Trojans into opening their gates to a great Wooden Horse, within which Greek soldiers lay hidden. Once inside the walls, the Greeks routed the city, killing and enslaving all. The Greeks won the war, but by his advice, Ulysses’ led the Greeks to commit an act of treachery. The Trojan War was won by deception, not through noble acts or strength of arms, nor by virtue of character. For that reason we have inherited an old saying: “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.” Ulysses became to the medieval mind a spiritual thief because he robbed his fellows of their moral integrity and their good name.

Assisted suicide is a Trojan Horse, a false gift. It looks like compassion, but from the standpoint of Catholicity, it robs the elderly of their integrity, and they are led, at the end of their lives, to think that what is expedient (oftentimes for others), is no sin. The language of legalized euthanasia is deceptive; the phrase “dying with dignity” is used to give a moral tinge to what is essentially suicide. Who benefits? The government saves the cost of hospitalization and treatment and indeed euthanasia is seen as a financial benefit.

The confusion about good and evil in which contemporary society exists makes it very difficult to defend “old beliefs.” In that vacuum of confusion, legislators and courts exercise power, leading the weak, poor, and elderly to think that wrong is right, and assisted suicide is no sin.

The legalization of euthanasia is an opportunity for Catholic Christians to speak the truth to power, to remind people of the moral reasoning of the faith. Ironically, and in an unthinking way, human beings who daily exhibit intellectual brilliance in advanced medical technologies, live in ignorance of how to use what they have invented for the common good. We live in a day and age when people of highest intellect deny the good of that intellect in refusing to exercise their responsibility in moral reasoning. Should not doctors use their skills and medical technologies to cure rather than kill? We have the power to keep most people out of pain until death.

It is left to Christians to teach the basics of moral reasoning, and even more importantly, to emphasize, for those who can hear, the sovereignty of God over life and death, His sovereignty over all creation until the end of time. It is more compassionate to help and comfort the sick and dying, to be with them until the end, than to precipitately end that life by advising them to die. My mother was close to death when she chose MAID, but even so, it is a tragedy for the elderly, no less than the young, to die too soon.