The explosive dinner scene in Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life evokes turbulent emotion in anyone whose memories of the family table echo a painful similarity. Even in the other mealtime scenes of this otherwise stunning film about the mysteries of suffering and its interplay with grace, there is the feeling of repressed discomfort, the idea that we sit up straight, exercise perfect manners and finish our peas, no matter the mood or temperament of those around us. Is this what it means to gather at table?

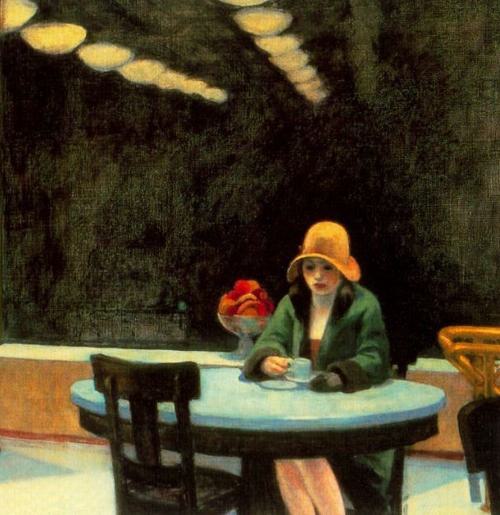

The Norman Rockwell ideal of the happy family at table has been seared into the American consciousness for decades, and certainly, many families know and have experienced the grace of the shared meal, whether by sheer accident or intention. But without having to analyze current trends about who is eating when, where, and what, it is clear to the naked eye by looking at our frayed and decayed towns, families and bodies, that many are eating alone and, aye, prefer

to eat alone. If eating together hurts, there is a way to fix that.

A nephew, living as a missionary in Tanzania, returned home last winter to care for his dying mother, my sister. He had not sat in an American restaurant for five years, but a relative treated him and his wife to a birthday meal at one of our upscale national chains. The next morning over coffee, he lamented over what he had witnessed. “No one is talking. Children and even babies are holding tablets, and parents too are distracted, watching TVs on the wall or looking at their own phones.” Our conversation shifted to how anyone—these young ones or even we older ones—can feel valued or known when no one seems to want to listen for longer than 140 characters or look you straight in the eye. And how disarming it is when someone actually does.

Some colleges and universities, aware of the increasing isolation of their students, are spending big sums redesigning eating spaces with an emphasis on larger community tables, with the idea that students will have no choice but to talk to one another, or conversely, that the communal meal might actually be attractive. More broadly in our own communities, the current trend—for those who can afford it—towards thoughtfully-prepared, locally grown and ethically procured food suggests a cultural agreement that this is how we can find our way back. But to what are we finding our way back, exactly?

[T]here is an opportunity for encounter every time we come to the table, any table, the knowing that there is something more we are here for, not simply to rid ourselves of this ache in the belly, but to be continually remade. And yes, Christ is present, even here.

While some might disagree, even well-intentioned propositions to cure forgotten neighborhoods with more fruits and vegetables are not entirely disparate from campaigns for newer and better grocery stores in not-forgotten ones, slow and mindful eating practices, calming lighting and faux nature décor, even in fast-food restaurants. All of these trends at their real core speak to a common need to soothe and feed hungry souls, regardless of advantage or disadvantage. But if disconnectedness is our original human wound, can the food itself, its availability, abundance, or packaging solve our deepest hunger?

***

Screwtape could rest in comfort knowing how many of us who are not literally hungry are concerned with the belly these days. It was he, after all, who advised Wormwood to stay focused on gluttony by delicacy more than by excess.[1] Not that excess is not an insidious demon in its own right, as massive swathes of the population know deep down that something is wrong, and hope that maybe medication, more time at the gym, or a meal delivery program could heal their inner ache. But delicacy in all its forms is more clever and harder to root out. While we have the right to care about the basic dignity of the food we consume within the constraints of our busy lives, our collective over-focus on what is in our food, how it is grown, how much or how little we should eat, how it sits in our bodies and how it comes out is a decisive victory for anyone (Screwtape?) who desires that we lower our gaze from the purpose for which we are really here. And it keeps us isolated from one another.

Since the time of Christ, the desert fathers were some of the better-known intermittent fasters. The more disciplined of the hermits who followed their example would go for days without food, others might eat once daily at 3 p.m., or some later monastics, even to the present day, might follow a more moderate fast of perhaps one warm meal daily, accompanied by two smaller cold ones. The knowledge that our disordered emotions and individual appetites (and not just for food) must be destroyed in order to grow in holiness was the primary driver for doing battle against the Seven Deadly Sins (or, in the Eastern church, the Eight Evil Thoughts). But even the most seasoned hermits, as the Rule of St. Benedict affirms, frequently had to submit first to the rule of the community before being allowed to go into reclusion to do battle alone. They had to learn to pray, sleep, and eat with others.

The word “refectory,” as Fabrice Hadjadj points out in The Resurrection, means in Latin a place for remaking. So, at the refectory table, we come to be restored, to be reconstituted, to be remade. The food we eat actually becomes a part of us, unlike gasoline in a car which merely runs out. The gasoline does not become the car, but the food we eat does make more of us.[2] Hadjadj suggests that when we become aware of the miracle of our digestive systems, whether we deem them marvelously efficient or sluggishly faulty in our own bodies, our ultimate dependence on food for our existence should lead us to gratitude: “Hail to the chicken thigh without which I could not stand on my own two feet … to the poultry farmer … the Creator ... the chords of digestion … Hosanna to the breath of fresh air, without which my lips would be incapable of praise!” It is this poetry of our being that is the true foundation for mealtime thanksgivings and prayers.[3]

It is for no reason of mere formality that we give thanks at table, as if waving a blessing over the food. When St. Paul exclaims, “Whether you eat or drink, do all things for the glory of God,” he is saying, as per Hadjadj, that it is because of the glory of God that is within us and around us that we enter into gratitude and service for all things.[4]

This is not to say that we obsessively think about how this bread will be digested or this meat broken down, but rather that we acknowledge that we indeed are “earthen vessels…always bearing about in the body the dying of the Lord Jesus, that the life also of Jesus might be manifest in our body” (2 Cor 4:7a,10). And our vessels need sustenance to perform this task.

Which brings us back to the table, and the fact that we come to it often, hungry. Like animals to the trough, we must eat to keep going. In cars, on couches, looking at phones, or standing at the kitchen counter, we find ourselves either alone or with others, distracted by the pangs of hunger—either real or imagined—disconnected and yearning.

The tenderest scene perhaps in all of Sacred Scripture occurs after Jesus’ Resurrection. The disciples, having resumed fishing, see a man on the shore who, after their night without a single catch, says something like “try putting your net over there” and they do, and then they can’t pull the net in for the weight of the fish. “It is the Lord,” John tells Peter.

Peter, we are told, jumps overboard and races ashore before the others, and there, at dawn, it is indeed the Lord cooking fish and bread over a charcoal fire. “Come, have breakfast,” he invites, and no one needs to ask who he is because they know. There on the beach is the Table, the charcoal fire its own altar, the elements of raw fish and dough turned into food for their breakfast, and the Lord himself, the cornerstone, the real altar who has become the True Bread, offering to feed them.

Hadjadj makes the striking connection that Jesus in his glorified body doesn’t really need

to eat, certainly not from want. But he chooses to share the meal at Emmaus and at the shore, and in so doing, his glory is revealed in the ordinary. Therefore, we too, see that in our ordinary, there is glory.[5]

***

One November morning, I accompanied our daughter as she brought her belongings to a home for the elderly and dying, an apostolate founded by a consecrated sister in the middle of Oklahoma. We had visited before, and now my daughter was coming back to give it a try, living and working in the community. After the typical greetings, one of the women I had previously met asked if I could make lunch, since she had been up all night caring for residents and she knew, from our previous visit, that I would be happy to do it and had already learned my way around the kitchen.

The ministry is founded on the gospel simplicity spirit of St. Francis and therefore accepts all visitors and gifts of food or time as providence. I asked what was on the menu, and the woman said, “Leftovers today.” Sister’s diminutive mother was visiting and, being from the same thrifty generation as my own departed mother, was thrilled to usher me to the refrigerator and point out cold fried chicken from Church’s that someone had brought, along with leftover starches and vegetables which some might deem ready for the compost pile. Without hesitation, she said the vegetables could all be trimmed and used and the chicken pulled apart from the bones and surely turned into something. With this inspiration, I started cooking and decided upon a big stir-fry.

The long refectory table had been reset after breakfast, and it was not clear how many would be having lunch since visitors often drop in and are always welcomed for the meal. The residents were brought to the table in walkers and wheelchairs, water was poured, the food was ready, and it was time for the blessing. No one touched their water or lifted a fork until it seemed by Sister’s leading that the meal had begun. Oftentimes prayer requests are shared before the blessing, so there is frequently a brief time of waiting before everyone partakes.

As for me, I had believed I was fasting that day for a series of muddled and undisciplined intentions, and so I was conflicted about what to do. Sister’s mother said not to worry about it, if I was fasting, I should fast. So I sat with a glass of water. Everyone complimented the stir-fry and said it was delicious, what in the world was in it? I never so much as tasted it, and that always seemed so wrong—not to share the meal. From that day forward, I reflected on that simple, ordinary meal, the conversation that took place, and the final readings and blessing that mark the end of the meal when everyone is excused. Something was different that day and every day since. I had begun to understand the gift of the real communal table.

***

Those who have spent time with the Benedictine monks at Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey in northeastern Oklahoma have returned with a few interesting observations: meals are eaten in silence while the monks and visitors listen to religious or philosophical passages read or chanted by a designated brother. The act of feeding the body physiologically, if you think about how these monks do it, takes place in an associative way, considering that many of us know all too well the fractured habits of eating while reading or scrolling through a YouTube video, only to find our meal has ended because our plate is empty. At the abbey, when the bell rings, all eating stops, the meal has been had, and now there is work to be done. Also, during the Lenten days of fasting, three meals are still eaten, but they are made up of even simpler ingredients than normal and are consumed in a much shorter amount of time. The fast is not complete abstinence from food, but, rather, a significant modification in how food is considered to one’s day.

These simple lessons and seemingly random encounters at the communal table have me pondering. Is there something there there? Is it Grace? Is it the Lord?

In our present state of radical individualism, it may seem impossible to find our way back to what is true wholeness, as if this goes back to Eve and the apple. Must we know perfect harmony in order to sit down with others? And must the meal strike the right balance of conversation, color, texture, and ingredients? It is a joy to feast with like-minded friends, but what about finding communion with and offering it to those who suck fingers, slurp, and have nothing interesting to say? And what if that person (who sucks and slurps) is me?

Is this curb where I share a cold piece of bread with the man on the street a table? And this TV tray table with family members around who have to watch the football game tonight? And this table where I find myself alone often for lunch, because if we are honest, many of us are not at communal tables every day? Is Grace here too?

“For we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses,” the writer of Hebrews says. This means to the simple-minded that at all times the invisible world is far greater than the visible,[6] and that the saints and angels, my guardian angel, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are here in this space too, even when alone. If this is so, it is possible to consider that there is an opportunity for encounter every time we come to the table, any table, the knowing that there is something more we are here for, not simply to rid ourselves of this ache in the belly, but to be continually remade. And yes, Christ is present, even here.

Perhaps our time now at the solitary table might better prepare us to seek out opportunities to sit down with others. St. Romuald, the ninth-century monastic reformer and founder of the Camaldolese order, emphasized the importance of the hermitage within a community over the dormitory-style monastery, the purpose being that members of the community must learn first to know peace in their cells.[7] Our earthen vessels cannot offer what they have not first learned to receive. So, even in community, according to Romuald’s semi-eremetical rule, one must have time for solitude in order to share outside of oneself. In our time, if we desire to find our way back to the table and help others to do the same, we must patiently keep coming to it.

Some time later, I returned to the home for the elderly and the dying, this time with my mother-in-law. She had not visited before and missed her granddaughter. She herself is struggling with the cognitive ravages of age, but from the outside looks like the Queen. After a brief time of meeting residents and touring around, lunch was served. Sister asked her to sit at the head of the table. A new resident, a homeless man whom Sister had brought in for what was supposed to be a short stay, took an open seat to her right. He was badly in need of a shower, had long gray hair, only a few teeth left, and made no sense. I was certain my mother-in-law would be made uncomfortable by her lunch partner, but on our way home she remarked that she had truly enjoyed him, she really had. I had watched them conversing, this juxtaposition of a seeming have and have-not, and wondered.

A few weeks later, on a perfect Saturday morning, the Feast of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, I was back again. The archbishop was coming to consecrate a new Immaculate Heart altar in the tiny chapel on the property. I had heard the residents would be given priority seating in the chapel, which only seats twenty-five, and also would be seated at the main refectory table for the meal with the archbishop afterwards. The rest of us participated by live-stream from two overflow rooms inside the main house, other tables having been set up beautifully for the meal to follow.

And so, after the Mass ended, the front door was opened to welcome in the archbishop and the others from the chapel. With sunshine streaming alongside, I noticed that there, in the line, filing in behind the archbishop, was Sister’s newest resident, my mother-in-law’s former lunch companion, smiling from ear to ear, showered and dressed in his Sunday best and looking like a new man. He and the other residents took their places of honor, while plates of quiche and salad were brought to them. The archbishop offered the blessing. It was time for the feast.

Hadjadj makes clear he is not blurring the lines between the Eucharistic table and the common one. He says, simply put, that “the plainest chow should be experienced as an act of thanksgiving, and that our intestines should appear to us as a primordial and truly edifying rosary.”[8] And if Grace is truly present, it would seem there is no Table where could not be heard the words, “Come, have breakfast.”

[1] Cf. C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (New York: Harper One, 2001), 87–91.

[2] Fabrice Hadjadj, “Do You Have Something to Eat?” in The Resurrection: Experience Life in the Risen Christ (Paris: Magnificat, 2016), 88.

[3] Ibid., 89–91.

[4] Ibid., 91.

[5]

Ibid.

[6] Monsignor James P. Shea., From Christendom to Apostolic Mission (Bismarck, ND: University of Mary Press), 70.

[7] John Michael Talbot, St. Romuald’s Hermitage of the Heart (Berryville, AR: Troubadour for the Lord Publishing, 2021), 16, 157.

[8] Hadjadj, 96.