Paul P. Avallone SDP,

Keys to the Hearts of Youth

(New Rochelle, NY: Salesiana Publishers, 1999).

Saint John Bosco,

Memoirs of the Oratory of Saint Francis de Sales from 1815 to 1855

(New Rochelle, NY: Salesiana Publishers, 2010).

In 1988, to mark the centenary of John Bosco’s death, Pope John Paul II wrote a letter to the Salesians praising St. John Bosco’s unique contribution to the lives of young people throughout the world and to the field of education, especially through his educational method known as the “preventive system.” He urged today’s Salesians to rediscover, renew, and update their understanding of this innovative approach, the substance of which remains intact because it draws its inspiration “from the transcendent pedagogy of God.”[i]

Keys to the Hearts of Youth was written in response to the Pope’s invitation to a rediscovery. In it, Father Paul Avallone, an experienced Salesian educator and writer, explains the theory and practice of St. John Bosco’s preventive system, linking its inception to the experiences of the saint’s early life and in particular to a series of dreams, the first of which he had when he was only nine years old. Memoirs of the Oratory of Saint Francis de Sales from 1815 to 1855 was written by St. John Bosco himself, at the insistence of Pope Pius IX who recognized his holiness in his extraordinary work and life, and in the dreams that inspired him. Although Bosco was very reluctant to write his memoirs—putting it off for several years—his obedience to the Pope eventually compelled him to begin. He envisaged the memoirs as fatherly advice for his beloved Salesian sons, to help them know him better, to “overcome problems in the future by learning from the past” and “to make known how God has always been our guide” (30). The small volume was first published in English in 1989 and provides compelling insight into the mind and growth of the saint, not to mention the evolution of his educational idea.

Just as in John Bosco’s time, today’s young people are often adrift, affected as they are by family tensions and breakdown, discrimination and despair, influenced then by mass media and morally dubious celebrities, all the while lacking guidance in their disengagement from adults. More than ever they need guides to walk alongside them, full of confidence and warmth and a willingness to be present to them in their discovery of the world and of themselves.

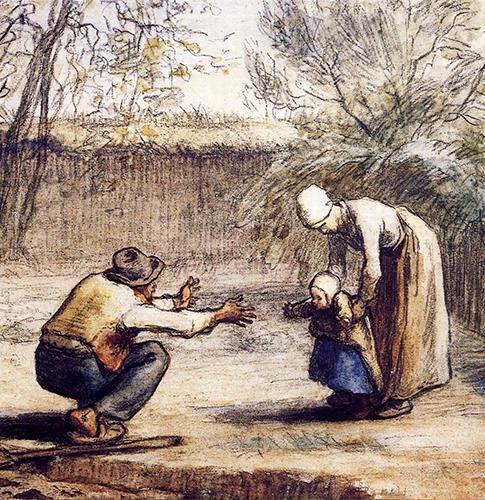

John Bosco was not an “educationalist” or theoretician, but a practitioner. He began to educate in response to his dreams (which urged him to teach virtue to a crowd of ragamuffins through gentleness and to “win the hearts of these friends by sweetness and charity”) and developed a method through trial and error, as he worked to save and to educate the alienated youth of industrial Turin. Starting with some boys recently released from prison and a few young men whom he befriended, John Bosco eventually housed and schooled hundreds of abandoned boys, guiding them to become “good Christians and useful citizens” by teaching them to read and write, playing games with them, instructing them in their faith, training them for work, and helping them to find jobs. His school at Valdocco, guided by his preventive system, became the center of his mission, and grew into a center for academic, creative, and vocational training as well as a model for Salesian schools throughout the world.

Avallone points out that Bosco’s preventive system was not particularly innovative, drawing as it did on the ideas of other contemporary educators who were questioning the repressive or punitive system of education so prevalent in European schools at the time. Bosco however was concerned with bringing Christ to the heart of the child and stressed that education was a “matter of the heart,” a matter of love. This emphasis meant, and still means, that his “system” had always to be flexible, capable of adapting to the needs and circumstances of the students in his care. His belief was that through the three tenets of his preventive system—namely Reason, Religion, and Loving Kindness—he could “appeal to the resources of intelligence, love and desire for God which everyone has in the depths of his being.” His conviction was that by creating a loving family atmosphere, he could guide his students towards a joyful and meaningful life, helping them experience the Gospel message through recreation, prayer, work, joy, and above all love.

By “Reason,” John Bosco referred to the need for a teacher to both teach and practice reason. He was, in particular, challenging the authoritarian pedagogical approach of the day, in which the teacher had little inclination to apply reason in dealing with the often impulsive and thoughtless actions of the young. Bosco sought to encourage teachers to understand their students—understanding, that is, their motives and enthusiasms, so that the teacher might start from “where they are.” Teachers must “walk alongside” their students, spending time with them, being available to them, and joining them in their activities and moments of recreation. In this way, thought Bosco, a teacher could nurture a creative and dynamic rapport in which the students knew explicitly that they were loved. (How often do teachers today shy away from such informal contact, “graced moments” as John Bosco called them, overburdened by paperwork, fearing legal repercussions, or lacking the confidence that the young would value their involvement!)

Recognizing that most of his students were profoundly ignorant of their faith and living through the perplexing time of adolescence, John Bosco undertook to offer basic catechesis and moral instruction. This is the second tenet of his educational method (i.e., “Religion”). Personal responsibility needs to be taught and demanded, thought Bosco; so he taught his boys to do good and avoid evil. He understood the deep aspirations of the young—for life, love, expansiveness, joy, freedom, future prospects—and he wanted to lead them gradually to see that their fulfilment lay in a life of grace. His memoirs reveal a real despair at the evil influences that his young people were prey to as soon as they returned to their homes or workplaces; and much of his work was inspired by his desire to save them.

Loving Kindness, the third tenet, required the teacher to create a familial environment; an atmosphere of love, peace, joy, encouragement, and praise and gentle correction... Inspired by St Paul’s writings to the Corinthians and by St. Gregory who said that the heart could never be conquered except by affection and kindness, Bosco tried, and by all accounts succeeded, never to punish in anger, and if possible, not to punish at all.

There is much in Bosco’s “system” that is uncontentious in modern schools. His intuition, that by gaining the confidence of his pupils through kindness and shared experience, he could then counsel, advise and correct, is confirmed by modern research in psychology and behavioral science. Modern education accepts that the young should enjoy learning, be encouraged and praised, and that teachers should walk alongside their pupils as they learn. Increasingly, schools recognize the need for moral and ethical instruction and there is much recent research into how to teach virtue in non-faith based schools (cf. Jubilee Centre for Character and Values, School of Education, University of Birmingham). However, there is something more that leaps from the pages of these books, particularly the Memoirs. John Bosco was a saint. Time and again, the most extraordinarily providential things happened. He was blessed with a prodigious memory, immense physical prowess, good and influential friends and confessors, miraculous happenings, timely solutions to the recurring problem of accommodating hundreds of unruly boys, and thwarted attempts on his life. But above all, he had confidence: confidence in his mission and in God. He gave this confidence to his young charges and they loved him for it. When, one Maundy Thursday, he realized some of them were unwilling to go with him to visit the altars of repose for fear of the ridicule and the contempt of onlookers, he responded by declaring they should march “in procession to make those visits, singing the Stabat Mater and chanting the Miserere.” When they set out, he reports “youngsters of every age and condition were seen joining us along the route and racing to join our lines” (Memoirs, 160).

In his introduction to Keys to the Hearts of Youth, Avallone reminds us of John Paul II’s great hope in the young, noting their enthusiasm and their desire for the truth. Just as in John Bosco’s time, today’s young people are often adrift, affected as they are by family tensions and breakdown, discrimination and despair, influenced then by mass media and morally dubious celebrities, all the while lacking guidance in their disengagement from adults. More than ever they need guides to walk alongside them, full of confidence and warmth and a willingness to be present to them in their discovery of the world and of themselves. St. John Bosco provides us with a timely and inspiring model, and these two books are a good introduction to him and his preventive system.

[i] Available at http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/it/letters/1988/documents/hf_jp-ii_let_19880131_iuvenum-patris.html.