Since my husband died last year, I’ve been dwelling in a hall of mirrors. His death was much earlier than it should have been, but late enough to see his first grandchild. And now, I find myself with impressions, images, and memories reverberating off the resonant boards of my mind. Did we do all that? Did we witness all those things?

For me now, it is first and foremost about the human fruits of our marriage. It is about our children, but also those they have allied themselves with, those they have married and will marry, and their children, a small procession appearing in the corner of my eye, on a new horizon which is nonetheless umbilically linked to the old. I watch our middle daughter negotiate the pleasures and perils of parenthood, alongside her young husband, and the focus, the point of it all, is not an abstraction. It is a person. A small child, now on her feet, running down the hallway, using her endlessly dexterous hands to interact with the world around her, filling the house with the merry sound of her verge-of-verbal babble. “Hi!” she says, waving her hand like the Queen. “Heyllo!” she calls, gracing us with a smile like a slice of sunshine passing across a rainy landscape. “Wow!” she exclaims, as I scoop her up into my arms and she points at something, a light or some bright tulips in a luminescent vase, or the family dog passing by with a nonchalant swish of his tail. It is as if she were saying: “Who made all this incredible stuff? Who cooked up all these wonders?”

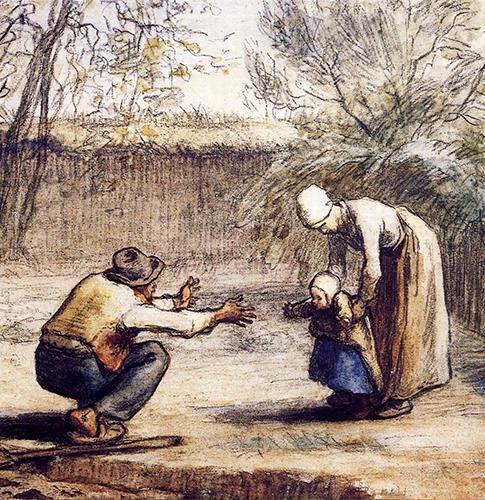

Contemplating the rapidity with which a baby develops, becoming a small child, learning to interact, play, walk and talk, all within the space of a year or two, reveals what it means to “educate.” For everything is there, in potentia, in the new human being. At the baseline of parenthood, our task is simply to draw it out: e-ducere. When people ask me how we brought up our children, that is all I can say, really. They came, we saw, God conquered. We simply tried to pay attention, we held them and played with them and tried to draw out what was in them, marveling all the way.

The family radiates a love which can only be called trinitarian. Not because the people in it are “holy” in a pious sense (we were not): but because that never ending waltz of love between persons―one, two, three and onward, outward―is the only thing that makes life livable.

Our first child, Teresa, was born when we were working in Boston, having recently entered the Catholic Church. The wonder of the new life in front of us echoed the wonder of our own new lives. Our discovery of the treasures of faith paralleled the exploratory hands and feet of our eldest child as she began to grapple with what it means to be part of the human family. Jokingly we photographed her soon after she learned to sit up, apparently reading an issue of Communio. Little did I know that this dear serious face would one day bend over such pages for real, after obtaining a degree in theology, and eventually provide invaluable assistance to us in our own work. Little did I know that this little girl would develop a beautiful voice and manner with which she would soothe a thousand problems into order.

The year after we returned to the UK, our second daughter, Sophie, was born. Now we had the chance to see what it meant for children to have companions, siblings. Very soon the two girls were inseparable. But they had very different temperaments and so we began to see how each child needs something a little different, even while they had to live “in community” with the rest of the family. The key to Sophie―named in part because all the readings the week she was born were from the Book of Wisdom―was her need to understand the deeper patterns of how people feel and live. As a toddler, this meant constantly testing the limits of parental tolerance. No wonder her favorite book was The Runaway Bunny (which she is now reading to her own little one―oh the layers of delight!). Sophie, like I, needed to describe, in words, relationships and their vicissitudes, as well as the symbolic resonance of the world in which those relationships take place, in order to be able to live and breathe freely. She learned to play the flute, then the harp, and set a poem by Tolkien to music, all because of the resonance of sound, the enchantment that word and note could strike in the ear. Like me, she became a writer.

Once we had more than one child, we began to see how the quality of attention parents give to each individual child can help them become a better functioning part of the group, precisely because they feel secure in themselves and loved for who they are, not for who we might wish them to be. Tiffs and tantrums are inevitable, but if children feel they are equally loved and have an ineradicable legitimacy in the heart of the family, they get over those, and learn from them. They learn to be moral beings by being treated as though they are capable of being just that. They learn to love because they bask in your love. They learn to learn because you are passionate about learning. They learn to pray because they catch you at it.And they learn the spiritual sense of time, because you weave a familiar pattern of sacredness around their days, not such that other things are stifled, but rather like rosary beads which space out the events of daily life, giving them meaning and structure, keeping their mystery.

When our third daughter was born, she was above all a mystery. We named her Rose-Marie, because in the days before I went into labor the roses were still in bloom…harbingers of late summer, spreading their scent into the season of harvest. She arrived three days before the birthday of Our Lady, on the very day they abolished the Communist party in the recently disbanded Soviet Union. Her older sisters clustered about her in the hospital with miniature roses and soft toys, caressing her soft cheeks and asking if they could hold her. Thus motherhood was born in them too, the notion that they could encompass another human being in their arms, wrap their soul about her and rejoice with God that this tiny creature came among them with all her strangeness and promise. They held Rosie’s hands as she learned to walk, they dressed her up as a tiny hedgehog, they taught her to sing. Later on she became an artist and a musician. She was imbued with a vision which had to be expressed. Her older sisters helped that to gestate, by the quality of their own attention, the security of the love they wove about her, in collaboration with us: so that her voice could soar and her hand could use the painterly genes from her father’s family, the musical genes from mine. In the pursuit of beauty and harmony, a passion that all of us shared and that her father wrote about with such eloquence towards the end of his life, our youngest child more than made up for the fact that we were not granted any more children after her.

* * *

The primary classroom of the family is of course the kitchen. Our children learned to cook because it was a chance to learn practical skills whilst having a good conversation. In striving after something that would taste good, natural motivation encountered the requirements of discipline and skill. This took time and a fair amount of spilt milk and broken eggs. But my daughters eventually became the bakers I had struggled and never quite managed to be. On the way there they mastered the basics, too. One day they shut us out of the kitchen and insisted they were going to handle supper (our eldest, always the careful, responsible one, was by now old enough to invigilate safely). An hour later we were invited in to eat overcooked pasta in tomato sauce with an accompaniment of fish fingers. All beautifully presented, of course.

I realize now that we instinctively followed the intuition about children that Maria Montessori also had: that you can educate them from an early age to take responsibility for their actions. The culinary experiments typified this approach: by learning to cook, you learn to do something serious and central to human life―to provide nourishment. But you also learn that order, proportion, respect for the laws of chemistry, and timing are all crucial if the experiment is to succeed. You learn manual skills whilst focusing on a profoundly human and incarnate objective. O taste and see: this is both the fruit of the earth and the work of our own, human hands.

The secondary classroom of the family is the dinner table. Ours was always open, and noisy. We never managed to abide by the principle that children should be seen and not heard. We talked about everything at that table, even when they were quite young. As they grew into teenagers, their peers joined us and enlivened the conversation even more. By eating with us, both adult and non-adult friends came to know what we were about. And we came to know about others, which is important, if you are not to live in a ghetto. Grace was said, yes, but grace was implied too, in the human discourse that followed. The whole of our family life came to revolve around that table, those meals, that endlessly repeated and embellished conversatio. The most perplexing questions could be raised here, discussed, not necessarily resolved all at once; but at least they were there, on the table, where they could be reflected on.

The deepest level of discourse was reserved for bedtime. We fell into a fairly byzantine regimen during which Strat or I would read our favorite fantasy (Tolkien for him, George MacDonald for me), for far longer than was really warranted. Our youngest daughter is still addicted to being read to. Bedtime prayers were woven in, and as the girls grew older, the serious conversations about the more delicate issues of growing up, all its wonder and weirdness. The best way to preserve your children’s innocence, I have found, is to revere their childhood so that they come to revere it too, even after they have passed out of it. This, however, should be done without hampering their journey into maturity.

Form and content cannot be separated when you are educating children. You teach them to be kind by being kind, to be just by being just, to listen by being a good listener. You teach them that failure is not the end of the story by being contrite after you have lost your temper, or trying to laugh when something goes wrong. You teach them about God first and foremost by smiling into their tiny faces, then by being there for them when they call. In some sense our children were as much our teachers in faith as we were theirs, because they challenged us to take our faith seriously enough to do something about it. I didn’t preach (that’s for the preachers) – I tried to explain, as best as I could, being honest when it got too difficult and referring the most difficult issues to the professional theologian in the family. He referred the matters of the heart to me because, well, that’s my thing.

We endeavored always to feed the imaginations of our children where faith was concerned, and to foster a social context in which that faith could grow in community. To this end I, to a certain extent, shelved my professional life as a writer in order to concentrate on catechesis and youth work. I organized pilgrimages, parish events, and adoration at the crib because Epiphany was a template for the host of smaller epiphanies when the Host was elevated at Mass. I tried to swallow my embarrassment when my children turned the holy water green after an over-enthusiastic use of the felt-tip markers during the children’s liturgy, or ran riot after discovering the wonderful acoustics in the church.

Our children eventually became contributors in their own right, playing in the little orchestra at the family Mass, helping to organize fund-raising events and oversee teenagers at World Youth Days. When I branched out into the theatre as a means of exploring the life of faith in the ecclesial community, our eldest daughter developed her considerable directorial skill as a means of making the vision incarnate. When her father was very ill, our middle daughter used her writing and networking skills to organize the now legendary “Cap-for-Strat” campaign to keep her father’s spirits up (having no idea it would go viral in the way it did). On the evening of her father’s funeral, our youngest daughter opened an exhibition of her degree work and dedicated it to him. This was not a sentimental gesture: as the statement she read to our family and friends explained, her father’s ideas about form and beauty were at the very core of her practice as an artist.

There are so many clichés about family life. It is, of course, very true that “the family that prays together stays together.” But it is also important to laugh together… and cry together, sometimes. To me the definition of a family is the place where you can be vulnerable, where you can fail, without anyone else dining out on your misfortune or foolishness. The place where you can share without sacrificing your privacy. The place you can always return to and be known and loved as who you really are: where criticism is an extension of appreciation, not malice or envy. The place where others will take genuine delight in your accomplishments, and offer genuine and swift assistance in your troubles. The family radiates a love which can only be called trinitarian. Not because the people in it are “holy” in a pious sense (we were not): but because that never ending waltz of love between persons―one, two, three and onward, outward―is the only thing that makes life livable.

This is all you need to know in order to educate children. There is kenosis too, of course. Suffering. You have to be willing to be stretched, yes, sometimes to the point of utter exhaustion, the breaking point where you are running on empty. You have to be honest about your slender resources as human beings. You have to be able to say, I cannot cope if you continue to do this, and you need me to be able to cope. And prepared to say, patiently, no, don’t do that, it-will-do-you-no-good oh-dear-what-did-I-say, oh well...tomorrow is another day.

There is always another day, to see what a gift your children are, what a gift we all are to one another. As the women of our family cluster together in this shocking year, missing the gift that the husband and father was to all of us, we remember that this new day is an eternal one, that the story-telling goes on, and that the sacred table of love has been laid forever, and cannot be taken away.