In the 1980s observers from different quarters voiced concern over the state of the American family. Though emerging a mere decade after the introduction of no-fault divorce, the data from such varied fields as education, counseling, social work, and law enforcement suggested the same thing: as divorce loomed ever-larger on the social scene, the family was increasingly unstable and children from homes thus broken were faring poorly on any number of indices. Interestingly enough, concern over the state of the family was not new. Writing in 1953, eminent sociologist Robert Nisbet noted, “Nowhere is the concern with the problem of community in Western society more intense than with respect to the family. The contemporary family, as countless books, articles, college courses, and marital clinics make plain, has become an obsessive problem.”[i]

For Nisbet, the psychologists, ethicists, and pastors of his day were undertaking a nearly futile task, namely, to shore up the affective bonds of marriage and family in an era in which the family’s institutional importance had declined dramatically. According to Nisbet’s reading of history, in order for institutions like the family or church to retain authority, command respect, and elicit devotion, they have to have enduring functional significance, that is, they have to do what other social organs cannot. Moreover, these indispensable functions have to be recognized as such within the larger social order. But the modern period, he insists, has been characterized precisely by a progressive expropriation of the functions once resident in the family and household. In an earlier age, the household was the site of economic production, education, care for the sick and aging, and the transmission of a religious heritage; these important activities were what bolstered the ties of kinship. As Nisbet summarizes, “[T]he family was far more than an interpersonal relationship based upon affection and moral probity. It was an indispensable institution” (60).

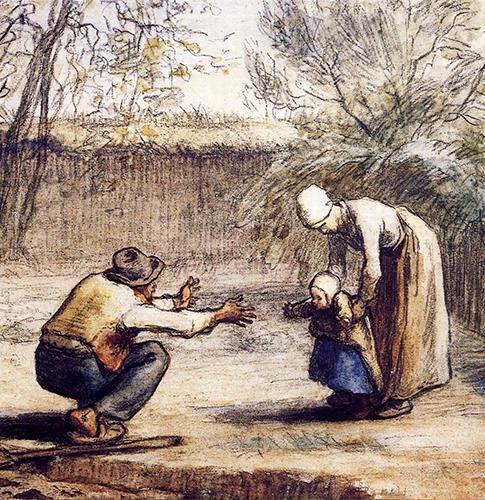

Parents are teachers, the first teachers; the home is a school, the first school. Its “curriculum” concerns life’s most profound truths and deepest mysteries, revealed in the quotidian realities of domestic life.

Not so by the 1950s. As Nisbet saw it, the social landscape at mid-century evinced the triumph of liberalism whose logic and dynamism paved the way for the omnicompetent state and corporation, both of which undermined the richly variegated social order of the medieval period mainly by appropriating the functions formerly belonging to the institutions of civil society. “Our present crisis,” Nisbet remarks, “lies in the fact that whereas the small traditional associations, founded upon kinship, faith, or locality, are still expected to communicate to individuals the principal moral ends and psychological gratifications of society, they have manifestly become detached from positions of functional relevance to the larger economic and political decisions of our society. Family, local community, church, and the whole network of informal interpersonal relationships,” he continues, “have ceased to play a determining role in our institutional systems of mutual aid, welfare, education, recreation, and economic production and distribution”(54).

Nisbet paints a sobering picture, but his larger argument in Quest for Community actually provides grounds for hope, since his thesis about the decline of civil society vis-à-vis the centralized state attests to the power of ideas. The fate of the family, kinship network, neighborhood, guild, and church was not an accident of history; these social institutions were not simply victims of unidentifiable, impersonal forces. Rather, Nisbet shows quite convincingly that a philosophical revolution, a revolution in ideas, lay at the origin of modernity, and that the political and economic developments of the last four hundred years owe much to a specific vision of man and the cosmos—one that can and should be challenged. And, for purposes of this essay, it should be challenged with respect to its understanding of the family and education.

As noted above, in Nisbet’s analysis, education was once the precinct of the household, informed from first to last by the values and aspirations of the family. Over the course of a few centuries, however, this function was moved into the public realm, largely appropriated by the state. So complete has this appropriation become in our day that boards of education throughout the U.S. have adopted curricula and social policies directly at odds with the religious and cultural heritage of their students, leaving parents hamstrung and helpless. (Think, for instance, of the oppressive “gender inclusion” mandate imposed on the children of Massachusetts a few years ago.) Both the schools and the parents in this scenario labor under a grave error, namely, that the state, through its pedagogical arm, is the preeminent authority concerning the education of children. This error is subtly coupled with another: the state is not beholden to an objective standard of natural justice, truth, or goodness. This modern situation would not surprise Nisbet; he might have predicted it. An expansive and intrusive state overrunning the authority of parents is simply the logical result of liberalism come to the schoolhouse.

But liberalism is not the only public philosophy on offer. In an insightful, courageous, and engaging book, Reclaiming Catholic Social Teaching: A Defense of the Church’s True Teachings on Marriage, Family, and the State[ii], Anthony Esolen helpfully reminds us that there is an alternative vision of the social order available, and its vision of man and his communal life is beautiful. As he well conveys, at the heart of this vision is divine love—surely a surprising starting point for social-political thought in our day. But Esolen insists that we won’t understand law, the state, the economy, or any other facet of our common life unless we approach it comprehensively, which requires theological reflection. Catholic social teaching provides just this sort of reflection.

The cornerstone of Catholic social teaching, he observes, is the concept of the imago Dei. Man is made in the image and likeness of God, who is a loving communion of persons. Man is thus made for communion, divine and human, a fact symbolized and realized through the sexually differentiated body. “Male and female” he created them. As Genesis makes clear, man and woman together image the relational God—supremely so when they become, indissolubly, “one flesh” and engender new life. Marriage and family, Esolen rightly insists, are natural realities, designed by God for a sublime end: the full flourishing of every human being in a joyful communion with God.

Many elements of our culture obscure this point. From Hollywood to Madison Avenue to Capitol Hill, the genuine nature of the body, sexuality, marriage, and family is assailed. Esolen underscores how pernicious the political assault on these realities is by reminding the reader of an elemental truth (strenuously defended by Leo XIII): such institutions as marriage and the family are pre-political. Neither is a creature of the state; neither can be intruded upon by the state; neither can be redefined by the state. Rather, the state is in the service of man and his primary societies, marriage and the family. When it adopts policies inimical to the flourishing of either—no-fault divorce, homosexual “marriage,” “safe” fornication training—the state has ipso facto violated its charge.

The temptation for the state to overstep its proper bounds is perennial. Today, the temptation to encroach upon the precincts of parental authority is especially powerful, given the frailty of the family. Esolen cites one particularly striking example in this regard, the case of Canadian education officials declaring themselves to be “co-parents” (87): Nisbet’s declension of the family taken to its logical conclusion. But Esolen won’t surrender the family and its prerogatives, especially concerning education. Drawing upon a central tenet of Catholic social thought, he avers, “Parents are to raise children sound in both body and soul. Their prime duty after working for one another’s salvation, is to teach their children what will avail them in this world and in the next” (85, emphasis in original). Parents must orient their children toward God, protecting them from falsehood and corrupt influences at large and in the schools and nourishing their minds with “works that form the imagination and move their hearts and minds to love the truth” (87).

Esolen’s brief but illuminating discussion of the educational role of the family recalls the insights of Familiaris Consortio, an encyclical of John Paul II that should be required reading for any serious student of education. The depth and beauty and power of this text are difficult to overestimate. It is a substantial remedy for the problem Nisbet identifies—the family becoming evacuated of its functions—because the document resoundingly affirms that parents are “the first and foremost educators of their children” (36). Indeed:

The right and duty of parents to give education is essential, since it is connected with the transmission of human life; it is original and primary with regard to the educational role of others on account of the uniqueness of the loving relationship between parents and children; and it is irreplaceable and inalienable and therefore incapable of being entirely delegated to others or usurped by others. (36)

Parents are teachers, the first teachers; the home is a school, the first school. Its “curriculum” concerns life’s most profound truths and deepest mysteries, revealed in the quotidian realities of domestic life. Through steadfast fidelity and service to one another, spouses teach their children what it means to love; husband and wife become thereby “the first heralds of the Gospel for their children” (39). Their sons and daughters are thus given an intimation of divine love—faithful, generous, self-diffusive. Building upon this experiential catechesis, parents further “their ministry of educating” by “praying with their children, reading the word of God with them and by introducing them deeply through Christian initiation into the body of Christ—both the Eucharistic and the ecclesial body” (39).

The lessons learned in the daily rhythms of the home are profoundly formative, teaching a child what it means to be human, what it means to be a Christian, and how to live in a community. As John Paul II observes, “All members of the family, each according to his or her own gift, have the grace and responsibility of building day by day the communion of persons, making the family a ‘school of deeper humanity.’ This happens,” he explains, “where there is care and love for the little ones, the sick, the aged; where there is mutual service every day; when there is a sharing of goods, of joys and sorrows” (21). A child thus formed can enter the world equipped to serve and celebrate it.

The intimate pedagogy of a child’s heart and soul, so tenderly described by John Paul II, can only take place in the family, because a mother and a father, sisters and brothers bear a uniquely privileged relationship to him. Nisbet need not despair. Whatever the pretentions of the modern state, the family alone is the “domestic church” and the primary school of love.

[i] Robert Nisbet, The Quest for Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 1953; Reprinted 1969), 58.

[ii] Anthony Esolen, Reclaiming Catholic Social Teaching: A Defense of the Church's True Teachings on Marriage, Family, and the State (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute Press, 2014).