Donal Mac Manus was born in Dublin in 1971. He earned his Bachelor of Design (1995) and Higher Diploma in Art and Design Teaching (1998) at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin and then a Masters in Fine Art (2001) at the New York Academy of Art. Later, he earned a Masters in Architecture, Art and Liturgy (2010) at the Università degli Studi Europea in Rome. In addition to producing his own artwork in studios in Rome, Florence, and Dublin, Mac Manus has founded several academic institutions: the Irish Academy of Figurative Art in Dublin (2004); the Sacred Art Studio in Florence at the Monastery of San Marco (2007); and the diocesan Sacred Art School in Florence (2011). A recently filmed documentary on Mac Manus’ work—Taking Beauty Seriously—will be released soon.

Humanum sat down with Mac Manus near the National Gallery in Washington DC, where he was spending some time copying the Masters.

A New Approach

Humanum:You have set up various schools and studios (in Rome, Florence, and Dublin). Do you have a distinctive approach to art?

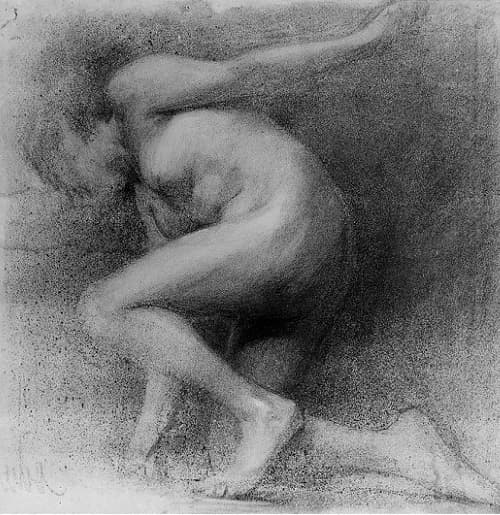

Mac Manus: Essentially, I try to start with the “music” (the “gesture”) then impose a bit of “architecture” (the “triangle”). It’s a play on the relationship between order and chaos. I find it most effective because it keeps the dance alive. It becomes a real relationship with the work, the model. When the head, chest and pelvis are correctly relating to each other, I then work the rhythm of the muscles between these structural forms, and on through the rest of the body. The important thing is not to get stuck in either extremes of gesture or anatomy, but to keep the work alive and really present.

Humanum: What do you think is going on in contemporary art?

Mac Manus: Modernism is a reaction to the calcification of artistic ideas in the academic mode. But in fact, both stem from a legalistic approach: they are both defined by rules. The academic style sticks to them at all costs. Modernism rejects them altogether. “There are the rules and I’m going to break them.”

The Christian, though, is not defined by rules. The Law enters the mind and penetrates the heart, so that you work from the heart. I approach my art the same way as I approach my faith. I am not Islamic. I am not Hebrew. I’m Christian: and Christianity is not a “religion of the book.” It’s not a religion of Law. It is a religion of the Person—it’s about an encounter with a Person. The Person penetrates your whole being and transforms your heart. And you work from your heart.

Humanum: So, the rules don’t matter?

Mac Manus: No! Rules matter more than ever, in that they matter in your heart. It’s rather that the Law—the “rules”—have penetrated your mind and transformed your heart.

Christianity and the Visual Arts

Humanum: Would you say that Christianity brings to the visual arts a distinct understanding of the body with respect to those who came before? If so, what is it?

Mac Manus: As I see it, the emphasis of the Greeks in the 5th century B.C. is on the profound penetration of truth—I am thinking here of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle. The visual manifestation of this reveals itself in ideal beauty. And that ideal beauty is very much an exterior beauty. It comes out in sculpture, where the ideal features of the human being are expressed in the exteriorbeauty of the body. In architecture, the pillars of the temple carry the emphasis, for example. It’s very elevated.

The emphasis of the Romans in the 2nd century B.C. to the 2nd century A.D. is more on interiority. You see this in their portraiture where they offer a deeply psychological, individual account of the person, in contrast to the ideal one. You can see that in Roman architecture where the interior is emphasized. (Think, for example of the Roman Basilicas, where all the beauty is on the inside).

With Christianity the exterior and interior are brought together. This is evident in the Florentine Renaissance, where the ideas of both of these great cultures are reborn—which is the meaning of “renaissance.” This happens in the Medici court, where the great historians, theologians, and philosophers discuss the ideas of the Greeks and Romans as they share meals together. And who is welcomed to that table, but Michelangelo? That’s where things really take off with the visual arts. His artistic and manual virtuosity is exposed to these ideas. He starts to communicate them through visual form, through sculpture in particular, and later through painting. This has a profound effect on the culture. It creates the concept of the “genius artist” who thinks with his hands, his manuality (as opposed to the artisan who just repeats, who doesn’t think). He has an extraordinary manual ability, as well as an extraordinary mind. He is very sensitive, extremely versatile and eloquent: he penetrates deep into his subject. Michelangelo is, of course, building on the shoulders of Masaccio and Giotto. But Michelangelo breaks the mold.

But all of this really starts with St. Francis. He is the ground-zero of Western Christian culture, because up to him the East and the West were pretty much in line, with the stress on the Divinity of Christ. It was St. Francis who brought the humanity of Christ to the fore, so much so that he actually received the stigmata. He embodied the idea. (Putting it in today’s terminology, he had a psycho-somatic experience.) Obviously, it is a divine intervention too. The greatest followers of St. Francis were Giotto and Dante. They transformed Western culture. And everyone after them was profoundly transformed by them. The suffering Christ is basically the source of our entire culture.

With respect to the ancients, what comes forth is not so much heroic or ideal—as with the Greeks, nor psychological—as with the Romans. The ideal is not so much about power. Or rather, there’s a different power in play: the power of love. And Christ manifests that in his vulnerability. The whole Crucifixion is a crazy image—it’s like putting somebody up there in an electric chair!

In my crucifix, “Corpus Christi,” I bring together this fact that God is God and becomes man. There I am contemplating God in human form: in my art, my primary grammar is form. I am asking myself: “Do I really believe that God was a body?”

Theology of the Body

Humanum: During your time at New York Academy of Art you came upon John Paul II’s “theology of the body.” And you started reading groups with fellow students. How did that come about?

Mac Manus: Art students learn everything about the human body except about what it means. So, there was a vacuum to be filled. We would meet on Friday evenings at 8:00 P.M. The room was packed and the discussions dynamic. Sometimes it would go till midnight and beyond. Many came close to the faith.

Humanum: In a nutshell, what was the meaning that the students discovered in the Theology of the Body?

Mac Manus: The basic message they got was that the body was a gift.

The two most deconstructed areas in Western civilization today are sexuality and art. The high-priests of this deconstruction are Derrida and Foucault with their idea that every relation is power-driven. At the heart of this program is the contraceptive culture. Everyone today is the child of a contraceptive culture. The Irish referendum on abortion in May would not have been thinkable were it not for the contraceptive culture. Essentially the contraception culture has taken the lynchpin out of culture—what holds culture together—the truth and meaning of human sexuality. Without it the whole thing collapses. You deconstruct that, you deconstruct marriage. You deconstruct marriage, you deconstruct family. You deconstruct family, you deconstruct society. Really everything stems from that core.

What is needed now is a “reconstruction” of the truth and meaning of sexuality. That has been achieved by John Paul II. There’s a blue print there that is perfectly appropriate. It has been extremely effective, both in my personal experience and in the lives of people that I’ve helped. All kinds of people have been healed by this and brought back into the faith. That’s really a core point.

The idea that the basic meaning of the body is gift reverses the message of power that has so permeated our idea of sexuality. It shows the deeply positive “message” carried by the body.

And I approach visual deconstruction in a similar way.

Love is more important than beauty. Both of them are totally in union with each other. They complement each other. And they are often seen as one and the same. But both of them are under attack. So, my approach is to try and heal both at the same time.

When I contemplate my culture, I see these as the greatest wounds. But first and foremost, there is the wound of the contraceptive mentality, which is the destruction of the truth and meaning of sexuality—in essence, the icon of love. That is the most important thing that needs to be addressed. I address it primarily through visual art. That’s my grammar. That’s how I see the world, and that’s how I contribute to the healing of the world as best I can.

The Nude

Humanum: You have much to say about the importance of the nude in art: that it is essential for “detoxing” society from its saturation in pornography, among other things. Is there a way of contemplating the human body as an expression of the image of God, rather than as the object of lust? Can the artist lead the way in this?

Mac Manus: The human body is the most fundamental form of beauty. Think about it. It is the primary mode of communication. Right now, we are speaking through gestures. Throughout history, we have always been fascinated by the human body. That means taking into account the muscles, the skin, the hair, gesture, drapery—everything.

The problem with pornography, Saint John Paul II said, was not that it shows too much of the body, but that it shows too little of the person. Pornography represses true beauty. Art, on the other hand, is a penetration of the truth. And the more you penetrate it, the more beautiful it gets. Desire needs to be channeled, so that it can reach its proper destiny. Drawing or sculpting the nude, or looking at it, can do this.

A Slow Art Movement

Humanum: Are we not perhaps in a new situation where the addictions of the age (pornography, social media) have made it difficult even to look up? What is needed in order for the audience to see the beauty (and truth) you are proposing as an artist? You may have something very striking to look at: but what if no one is looking?

Mac Manus: Drawing should be fundamental to education as such, not just for budding artists. Even life drawing. I think we need a “slow art” movement, just as we have a “slow food” movement. Art has the ability to slow us down and heal us of our distractedness. But artists too need to slow down. They aren’t looking either. They are not trained to look at or contemplate the Great Masters—or even nature itself.

Humanum: Does it matter where we look at paintings? Does the contexthave something to do with our availability to look?

Mac Manus: In my view, when we go to a museum, we are often visiting orphans in a hospital! Take for example, the Deposition of Christ by Caravaggio, which hangs in the Vatican Pinacoteca. There is the limp hand of Christ falling down towards the center of the painting, for that painting was meant to be hanging above the Altar—in the Chiesa Nuova—so that the hand would literally be pointing to the Body of Christ when the Priest elevated the Host!

Humanum: Do you see yourself as a “Christian Artist”?

Mac Manus: I don’t believe in being a “Christian Artist” in the sense that art should not be used to preach or indoctrinate. It’s not a means to an end. That’s what illustration does. Illustration is the projection of ideas through a medium. It has a role. And it’s perfectly valid. But that’s not what art is, not in the high sense anyway. Art is the natural overflow of the interior life of the artist. The point is that there is no need to dictate. In a talk at the Rimini Meeting, Cardinal Ratzinger said that beauty has the power to pierce the heart. That’s really central to my vision, and to the healing of contemporary culture. Because contemporary culture is so relativistic, you’re always confronted with assertions like: “That’s your truth….my truth’s different.” But Beauty is something that can bring people together. And if you’re smart enough, and you live the good life, then it will overflow in your work. That will catechize. It will bring people to the faith. But the reason is because you live, not because you want to change the world. People change because you love them. The important thing is to love and then, paraphrasing St. Augustine, “do as you please.” If you’re an artist, and you do that, then it overflows into your work. It is a perfectly natural thing. And it’s more effective because people don’t feel preached at.

Donal Mac Manus is a sculptor, painter and founder of the Sacred Art School. A sampling of his work can be found on his website.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Debunking the Myths of Pornography.