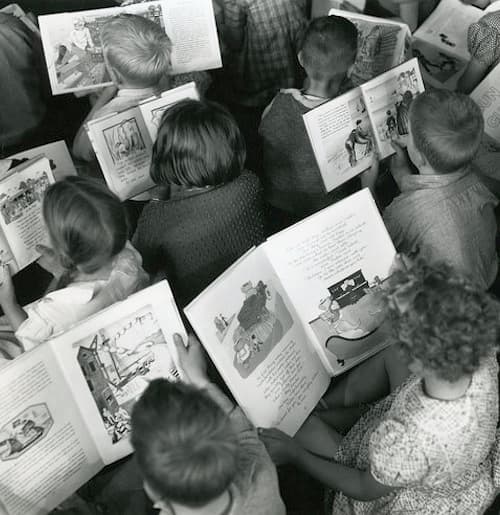

With this second issue on education we delve into the teaching and learning of the disciplines in the environment of the school, be it the home-school, the parish or public school, the high school, or the university.

Our first issue on education dealt with education in its most basic sense, that of being introduced to reality, where the “introduction” and the “reality,” as well as the “student” and the “teacher” find their expression in the fact of being born to a father and mother and then led out (educare) by them into the world, beginning with their world… The fact that a child takes his “first steps” into the world, “on his own” between his mother and father cannot but permeate what education means when taking up the disciplines, as we do now. Simply put, and quotably so, as G.K. Chesterton said: “Education is only truth in a state of transmission.”

It is right that in an issue on schooling, the authors, reviewers, and we the readers should sit at the feet of the great masters, whether they are our contemporaries or not. For this reason we inaugurate our first column of “ReSource: Classic Texts,” beginning with an address given by Benedict XVI to educators at The Catholic University of America, and a selection of texts taken from Chesterton’s famous What’s Wrong with the World. As always, leading thinkers are featured throughout the reviews themselves, in this case, Christopher Dawson, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Stratford Caldecott, our late and much missed founding editor.

It is also fitting that in such an issue, we have so many teachers represented as reviewers and feature writers, be they home-schooling mothers (Carla Galdo), high school teachers (Anton Schmid, Stella Schindler, Roy Peachey, Aisling Maloney), university professors (Michael Hanby, Steve Brown, Robert Lopez, James Gaston, Christopher O. Blum), a Deputy Head and two school founders (Robert O’Brien, Dale Ahlquist, and Marco Sermarini).

We could draw on Chesterton’s exhortation to return “the whole truth of a thing” against the backdrop of an educational culture resembling “one wild divorce court” as a way of summing up the cluster of inter-related concerns in this issue.

The first of these concerns is the divorce of education from history, from the “burden” of a received tradition and the place one thereby belongs to, beginning with one’s parents. As Chesterton said (again!), “the problem is not that man has lost his way—man has always lost his way—the problem is that man has lost his address.” In keeping with the dominant educational mentality, one is not introduced into a world, a reality. One constructs it (with the only thing one has received, “skills”).

The second concern follows from the first. It is the disconnection between education as “information” and education as a life-changing response to and service (“diakonia”) of the truth (Benedict), of that which is greater than oneself, that which is “for its own sake.” Having no original address, a person is hardly receptive to “settling down” to serve something or someone (including oneself!). Instead, this diakonia of the truth gives way to the utilitarian fever of immediate satisfaction where “cold pragmatic calculations of utility . . . render the person little more than a pawn on a chess board” (Benedict), a listless “worker” resigned to the hamster wheel of modern-day employment. It is no accident, many of our authors contend, that the loss of real local community, and the breakdown of the family—and even the promotion of this—follows so closely behind this second “divorce.”

The third concern is that of the divorce between education and the religious question. Here we look first at the cultural question concerning us in the West. Do we have any idea of the extent to which the world we live in is a product of Christianity—and for centuries now, of our rebellion against it (Dawson)? Do we realize, that is, how much the “palliated echoes and haunting fragments of Christian moral theology”—charity for the poor, human rights, legal equality etc.—“would not exist had our ancestors not once believed that God is love, that charity is the foundation of all virtues, that all of us are equal before the eyes of God, that to fail to feed the hungry or care for the suffering is to sin against Christ, and that Christ laid down his life for the least of his brethren” (Hart)?

But more broadly still—regardless of our cultural heritage—the bigger question is whether or not it is possible to educate and be educated with an indifference to the question of God, without becoming at the same time indifferent to what is essential to one’s own humanity. It would be hard, if not impossible, to separate the philosophical, artistic, and literary traditions from the longing for God as though the latter were just a cultural by-product of these, not their generative source. The connection between the religious question and human learning, however universal, is, of course, central to Christianity in a unique way, on account of the fact of the Incarnation of the Word, in the light of which “the mystery of man takes on light” (Gaudium et spes, 22). As Benedict says: “God’s desire to make himself known, and the innate desire of all human beings to know the truth, proved the context for human inquiry into the meaning of life.” It is precisely for this reason that the Christian world has had such a pivotal role in education as such, through the founding of universities, then high schools and parish schools (particularly in the US), not to mention filling religious orders to teach in them. It is for the same reason that it is incumbent on Catholic educators in particular to ask just what makes for a “Catholic” education, and whether or not it is enough to add a “religion class” or service projects on top of an otherwise secular education “soaked through and through with a contrary conception of life” (Chesterton). The question about the origin, current state, and fate of the Catholic school (and university) is not, however, a merely “parochial” matter. If Christians, by virtue of the Incarnation, are entrusted in a particular way with an “inquiry into the meaning of life”—that is, to education properly understood—then what they decide about Catholic education, they will decide about education as such. As Chesterton said, “take away the support and what remains is the unnatural.”

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and Senior Fellow at the Center for Cultural and Pastoral Research. She is the US editor for Humanum. She is married and the mother of three teenagers.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the editor of Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.