The Terry Fox Story

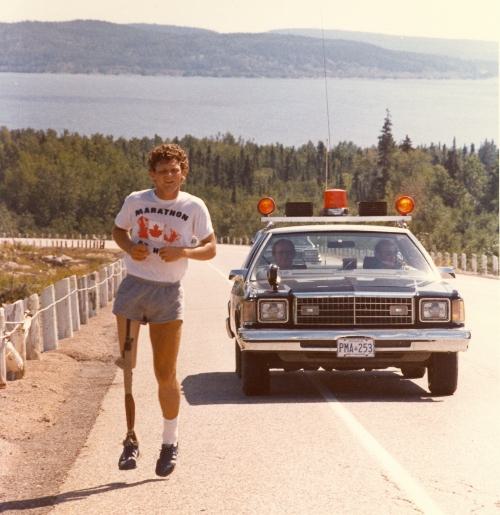

In the spring of 1980, a young man dipped his prosthetic leg into the Atlantic Ocean and embarked on a coast-to-coast run across Canada to raise money for cancer research. His name was Terry Fox, and he remains one of the best known and loved Canadian heroes of all time.

Terry was 18 years old when he had to have his leg amputated due to bone cancer. While undergoing treatment, he was deeply moved by the suffering he observed among the other cancer patients. Terry then resolved to raise awareness of cancer and funds for research in what became known as the Marathon of Hope.

With an artificial leg, he ran a marathon (26 miles) nearly every single day for 143 days. Although he died before reaching the Pacific Ocean, he inspired a nation. The Terry Fox Run has continued ever since with an astounding 850 million dollars raised for cancer research in his name.

Each year, schoolchildren learn the Terry Fox story and participate in a local or school-organized Terry Fox Run. This event is notable, particularly in such a pluralistic society, for its unifying character. It brings students together around a national narrative in which they can take pride and derive edification.

I still remember sitting on the gym floor watching the documentary about Terry’s life year after year through elementary school. I remember doing the Terry Fox Run around the schoolyard and how I ran harder and differently than when playing tag or soccer because this was a run that really meant something. I remember thinking, even as a little kid, that if I ever got cancer, I would want to run the race of that diagnosis—if only metaphorically—somewhat like Terry did.

The Terry Fox story is key to Canadian identity but, with the nationwide introduction of euthanasia, there is now a rival message about what cancer means in the life of a person. So far, cancer patients have been victims of Canada’s euthanasia regime in the greatest number. According to the Government of Canada’s own report, cancer is currently the number one underlying condition that leads people to ask a doctor or nurse to kill them. And, last year alone, 8,341 cancer patients were killed by doctors and nurses in hospitals and homes.

The Rival Vision

In 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that parts of the Criminal Code were unconstitutional by prohibiting euthanasia. In the Orwellian and startlingly unanimous judgment, the Court ruled that not facilitating euthanasia was an infringement on the right to life, liberty and security of the person. Responding to the pressure of this ruling, the federal Justice Minister tabled a government bill that swiftly passed through Parliament, becoming law just two months after being introduced. The principal feature of this bill was an amendment to the Criminal Code that created “exemptions from the offences of culpable homicide, of aiding suicide and of administering a noxious thing,” in order for physicians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists to participate in euthanasia and assisted suicide.

With hardly any public debate or even awareness, Canada legalized euthanasia and exempted medical professionals from the crime of homicide under certain criteria. At first, these criteria restricted euthanasia to adults with a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” who made a voluntary request to die with informed consent. Most people had in mind that this meant, for example, patients with terminal cancer.

If someone lacks the strength to stand, then you put your arm around their waist to steady them; you don’t push them over.

These judicial and legislative developments were bolstered by a longstanding campaign by Dying with Dignity, an organization that has been working for more than forty years to advance euthanasia in Canada. While students were learning the Terry Fox story, Dying with Dignity was launching local chapters across Canada and hosting assisted dying seminars at senior’s residences, community halls, and even places of worship. In fact, back in 2016, a priest from Toronto who used to celebrate a monthly Mass at a retirement residence told me that he got there one day only to learn that the usual room had already been booked by Dying with Dignity and that Mass was canceled.

Euthanasia has also undergone a rebranding as part of the campaign to gain public support for an act that was recently a criminal offense. Now, euthanasia in Canada is referred to—in law, politics, healthcare, and the media—simply as “MAID,” which stands for medical assistance in dying. This has deadened consciences, decreased ethical sensitivity, and blurred distinctions. The acronym is so ubiquitous that it is even being awkwardly used as a verb. An emergency room doctor in Ontario told me that a colleague had casually suggested, referring to a patient with terminal cancer: “We could just MAID her.”

Pushing boundaries and experimenting with what the public might tolerate, even euthanasia doctors attest to having made things up as they went along. In her euthanasia memoir, Dr. Stefanie Green reports explaining to a relative, “‘Mr. Winslow has requested an assisted death, so I’m here to help assess if that’s going to be possible. I’m from the MAiD team.’ In truth, there was no MAiD team: It was a fictitious club that I made up on the spot to try to sound more official.” Now, with millions of dollars of federal funding, Dr. Green has indeed turned her “fictitious club” into something quite official.

Proponents of euthanasia like to stress that it is a free, rational, and legal choice for individuals to have a medical professional end their life. However, this is certainly not the case for everyone. As soon as euthanasia became regarded as a reasonable solution to suffering, there was no legitimate basis for limiting it. Presently, in Canada, almost all of the safeguards have been removed and the eligibility criteria expanded to essentially include all grievously suffering adults. Now, scanning the news, you find such headlines as: “Facing another retirement home lockdown, 90-year-old chooses medically assisted death;” “Homeless, hopeless Orillia man to seek medically assisted death;” “She’s 47, anorexic and wants help dying. Canada will soon allow it;” “Canada will legalize medically assisted dying for eligible people addicted to drugs;” “RCMP called to investigate multiple cases of veterans being offered medically assisted death;” and, “B.C. man chooses MAID while waiting for cancer treatment.”

Despite the formal requirement that euthanasia be the result of a voluntary request, financial coercion, on a personal and national level, is without a doubt a factor contributing to Canada’s euthanasia crisis. Several years ago, at a Dying with Dignity workshop, I spoke with an elderly woman who told me directly, “Well, I think that my family would like my money, rather than to see it go to waste! I am the person who will choose to see my grandchildren looked after.” And, federally, in 2020, the Parliamentary Budget Office unabashedly published a cost estimate of the net reduction in healthcare costs due to the impending euthanasia expansion.

Euthanasia is also being raised with patients unsolicited—in many cases again and again—even when it has been refused. And doctors fear repercussions from their professional and regulatory bodies for not raising it as an option with any patient who might be eligible. This, understandably, has a demoralizing effect on patients. Simply put, nobody deserves to be told they qualify to be killed. Far from increasing compassion and options for care, euthanasia is making death more alienating and frightening for the dying person and more traumatic for those who remain to mourn their premature death.

Who Is Asking for Euthanasia, and Why?

Over the past four years, Health Canada has published an annual report on euthanasia. One of the most interesting data categories surveys the nature of the suffering of those who sought euthanasia. According to the latest report, “In 2022, the most commonly cited source of suffering by individuals requesting MAID was the loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities (86.3%), followed by loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (81.9%) and inadequate control of pain, or concern about controlling pain (59.2%).”

As a form of suffering leading to a request to die, “the loss of an ability to engage in meaningful activities” exceeds the categories of feeling like a burden, losing control of bodily functions, or suffering isolation or loneliness. If we take seriously the self-reported motivations of those seeking euthanasia, we find that the number one reason why Canadians seek euthanasia is existential.

But does a person ever actually lose the ability to engage in meaningful activities? What does “meaningful” mean, after all?

In his bestselling book, Man’s Search for Meaning, Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl says:

Dostoevsky said once, “There is only one thing I dread: not to be worthy of my sufferings.” These words frequently came to my mind after I became acquainted with those martyrs whose behavior in camp, whose suffering and death, bore witness to the fact that the last inner freedom cannot be lost. It can be said that they were worthy of their sufferings; the way they bore their suffering was a genuine inner achievement. It is this spiritual freedom—which cannot be taken away—that makes life meaningful and purposeful.

Robert Spaemann had a similar reflection on how a person can never lose dignity:

Why, though, is it impossible to go beneath that minimum threshold we call human dignity? It is impossible because that freedom that is potential for moral dispositions and concrete actions cannot be lost. As long as he lives, the human being is such a creature that we can and ought to expect him to align with the good. But he can only align with it freely. To anticipate his alignment of good, as well as to secure that free space required for such acceptance, are the ways in which we pay respect to human dignity.

The securing of that space for the person to continually align with the good demands the noble and necessary work of suicide and euthanasia prevention.

Some people are tormented by their impressions and fears of how they will be perceived by loved ones. A woman told The New York Times that, amidst her third bout of cancer, she was seeking an assisted suicide. “I don’t want my children, who are now 45 and 47 years old to have those memories of me at the very end,” she said. This reminded me of an Uber driver who told me that his father had been euthanized in their home in November. His father, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, had asked his doctor if he might make it to Christmas. The son, who had initially supported euthanasia but now found that his family had been traumatized by it, recalled that the doctor had told his father, “Perhaps. But it won’t be a Christmas with you that your family will want to remember.”

Who could resist the temptation to euthanasia upon hearing such a thing? We need to reassure our loved ones (and, by extension, we will be reassuring ourselves) that vulnerability will not lead to a rejection by our family, friends, and wider community.

This Concerns You

The practice of euthanasia within a society cannot but be corrosive to all. Like eugenics, euthanasia makes all of our lives more precarious. As soon as there are certain conditions for which it can be considered reasonable to opt for assisted death, those with the same conditions who do not do so are easily dismissed as foolish or even selfish.

Euthanasia also lowers the standard of care and minimizes our efforts and interventions. A woman was recently diagnosed with cancer, told she was ineligible for treatment in Canada, and offered MAID. She chose to seek treatment in the US and is doing very well. Thus euthanasia instills in us the sense that we are being given up on. The offering of euthanasia erodes the trust that is crucial to the doctor-patient relationship.

Euthanasia undermines all suicide prevention. As some disability rights activists have been pointing out, we are all only temporarily able-bodied. And so, as we age, we are left questioning, “If I suffer and find myself in need of care, will you leave me? Will you abandon me if I am weak? After a diagnosis, will you only offer me a hastened death?”

Euthanasia flattens our understanding of quality of life. Life always has quality. The opportunity to show tenderness, the ability to accompany our loved ones, and the occasion to practice courage in the face of illness and suffering nurture our humanity. To say that there is no quality or no dignity is to fail to understand the very meaning of these concepts. To refer to euthanasia as death with dignity is to insinuate that natural death is undignified. And, while dying is naturally humbling, bringing us “down to earth,” there is time to heal relationships, share affectionate words and gestures, and find peace.

Toward a Remedy

When someone is suffering and ill, it is normal for them to experience depressing thoughts, self-rejection, feelings of abandonment. It is critical, therefore, for others who surround this person not to capitulate to these feelings. When someone is tempted toward pessimism, the right response is for others to counter it, as Pope Francis says, “by affectionate pressure.” That affectionate pressure is so much more human than autonomy. It says, “I will fight for you, especially when you do not have strength to fight for yourself.” If someone lacks the strength to stand, then you put your arm around their waist to steady them; you don’t push them over.

I feel great moral urgency to promote and personally contribute toward better inclusion, intergenerational solidarity, and the assistance that others need to live. Part of this involves combatting generational, demographic, and ableist stereotypes and tropes that lead to discarding, discounting, and dismissing people.

We know that a generous response can make a difference. Terry Fox’s generous response to his illness changed the face of cancer research in Canada. His inspirational run to raise funds for cancer research means that there is now a high recovery rate from the kind of bone cancer he had. People seldom die from it and rarely face amputation like he did. What happens if we stop trying to heal and to cure but capitulate to the disease? How many cures or advances will we miss if we prescribe death instead of treatment?

During his cross-Canada run, Terry took a day off to go swimming with a kid who had the same cancer and an amputated leg like him. He considered it the most inspirational day of his life. This is a good reminder that, whatever we may suffer, we can find inspiration and solace in sharing our suffering with another.

As Lorenzo Albacete put it:

The most intimate encounter between human beings is through shared suffering. The communion of life born through shared suffering is the strongest interpersonal communion in the world, breaking down all barriers among human beings, and bringing us together through a bond with transcendence, with “something always greater than us.”

An intimate encounter and communion of life is something that each suffering and dying person deserves to experience. It is up to us to provide this encounter so generously that the person would truly not have wanted to die prematurely—and have missed it.