Roger W. Nutt,

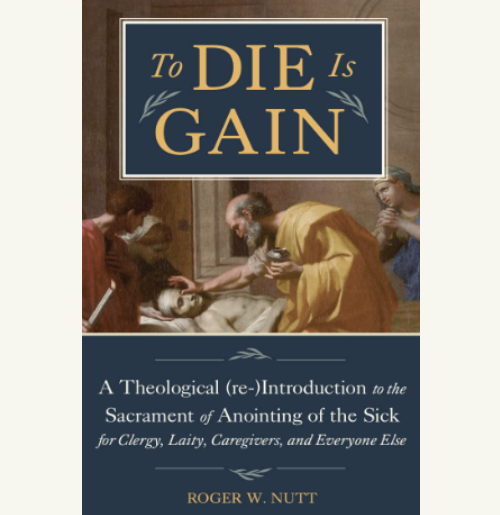

To Die is Gain: A Theological (re-)Introduction to the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick for Clergy, Laity, Caregivers, and Everyone Else

(Emmaus Academic, 2022).

It is often said that Vatican II was a “pastoral” council. But this misses the mark. If one were to look closely at the four major constitutions and their content, it would become evident that, although there is indeed a pastoral character, the focus of the Council went much deeper. Inspired as it was by the discovery of numerous Apostolic and Patristic works throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the conciliar Fathers led the Church in a reflection on her essential nature as the Spouse of Christ and her vocation of evangelization in the modern world. This is witnessed in the catechetical timbre of the documents which seek to reacquaint the People of God with their patrimony and renew a sense of awe before the splendor of the faith. It is more appropriate, therefore, to see Vatican II as a mystagogical council, a beholding of the mystery of salvation as an event in history that should elicit a response from the heart of every man.

Acting in this mystagogical character, the Council gives special attention to the “source and summit” of the Church’s life, namely, her liturgy. Part-and-parcel of an emphasis on the liturgy is a concentration on the sacramental life of the Church. Pastors of souls are therefore exhorted “to ensure that the faithful take part fully aware of what they are doing [in the sacraments], actively engaged in the rite, and enriched by its effects” (Sacrosanctum Concilium, 11). All seven sacraments are reaffirmed as key moments of catechesis and encounter with the Risen Lord.

Every sacrament not only serves as the preeminent locus of encounter, but, as such, a mode of education into the fundamental mysteries of the Christian experience and summary moments in the economy of salvation. One often overlooked, if not misunderstood, sacrament in this economy is “extreme unction,” which may also and more fittingly be called “anointing of the sick."

"[T]he sacrament [of the anointing of the sick] is a sure font by which the soul encounters the living God and is strengthened to surrender itself in confidence to the broken body of the Crucified Christ."

When we think of the sacrament of anointing, it’s usually associated with “Last Rites,” in other words, death. That is not entirely out of place even if it is one-dimensional. In fact, the anointing of the sick is informed by a rich theology and unveils in its action a core mystery of the faith proclaimed clearly in St. Paul’s letter to the Romans: “If we live, we live for the Lord; and if we die, we die for the Lord. So, whether we live or die, we belong to the Lord” (Rom 14:8).

That being said, the general knowledge regarding this sacrament is lamentably poor. For this reason, I find Roger W. Nutt’s recent book, To Die Is Gain, a welcome and informative discussion on the topic. Aptly subtitled “A Theological (re-)introduction to the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick,” it guides the reader not only in a description of the sacrament, but more importantly, a thoughtful reflection on its essential character in relation to soteriology, anthropology, and eschatology. In the author’s own words:

The purpose of this book … is to help all Catholics—indeed everyone—to better appreciate the profundity of this gift as a fundamental component of the Christian response to the crisis of suffering and death. It is my hope that by reflecting on the theology and spirituality contained in the Church’s teaching on the sacrament of the sick that we may all rethink death, and the meaning of our lives, in light of faith in Christ’s own death and resurrection.

Quite keenly, Nutt begins with a conversation on the current attitude towards death in popular culture. It is no secret that “death” is a dirty five-letter word in secular society. This, in turn, has influenced the Christian mentality, as even the most faithful will sometimes treat the reality of dying as something to be marginalized.

In contrast, Nutt re-presents the seminal claim of our religion, urging the recognition of the resurrected Christ as the hope of the human heart and the center of history. For in the Lord, we realize that dying is not the ultimate tragedy, but rather “dying without knowing one is loved, especially by God.” Likewise, the author offers a much-needed reminder of the “Last Things” or the eschatological component of our faith, of which death is the first.

This is not morbidity. On the contrary! To pretend we are created for this world and so spend our waking hours striving to artificially extend our biological lives is morbidity. To face our mortality, on the other hand, is the sure sign of a mature individual and a necessary aptitude of Christianity. In so doing, we open ourselves up to the deepest recesses of our souls which cry out for the living God who seeks us in the gaze of His glorified and risen Son. Only in this light does something like the institution of the sacrament of anointing make sense. We are able to minister, even to those who are at the end of their lives or in danger of dying, because the reality of death has been genuinely taken up and redeemed in the death of Jesus Christ. Thus, the Apostle is able to boldly declare, “Death where is your sting?” (1 Cor 15:55).

The body of the book—chapters two through four—offers one of the best expositions of the theological foundations of the sacrament of anointing I have read. Nutt treads the tricky tightrope of being intellectual but not lofty; relatable but not shallow. This is always the mark of an astute mind and a well-formed heart. Especially appreciated is his constant reference to the Tradition, as he seamlessly weaves in quotations and insights from the Scriptures, Patristics, and the Saints. It gives the correct impression that Nutt is not inventing or “reading into” the sacrament, but in fact laying bare its inner logic and how it has organically developed throughout the Church’s history. Rightly, Nutt draws on the wisdom of the Tradition to remind the reader of the long-standing and uniquely Christian intuition that death vis-à-vis the crucified and risen Lord is not only a passive reality, but is itself ennobled and empowered to become an expression of faith by merit of him “who was obedient unto death.”

If the above-written is not endorsement enough, I would suggest the book for chapter five alone as it picks up where Vatican II and the rubrics on anointing leave off, fleshing out the idea of a rite and how to move forward in an adequate understanding of the sacrament of anointing. It is especially helpful for me as a priest who regularly celebrates the Rite of Anointing with the sick and the dying. Nutt does a fine job of placing the sacrament in context not only in light of the sacraments of initiation (i.e. Baptism, Confirmation, and Holy Eucharist), but also the particulars of the ritual itself which are rich in symbolism and catechetical value. At the same time, the author makes sure to uphold their efficaciousness beyond the merely “horizontal” symbolic plane. The sacrament is not primarily intended to simply comfort or console the individual and his family members, even if it may do so in the moment. It is a legitimate source of grace where Christ is enacting his sacerdotal ministry as Savior via the ordained minister. “As such, the sacrament is a sure font by which the soul encounters the living God and is strengthened to surrender itself in confidence to the broken body of the Crucified Christ.”

There is more I could say of this little book. One of my closest friends is a professor of sacramental theology at the seminary, and I will certainly share it with him as I think our future priests should be well-acquainted with Nutt’s insights. Overall, this book is a positive contribution to the ongoing implementation and interpretation of the Second Vatican Council as we seek to let the genius of our Catholic faith shine as the sacrament of salvation.

Fr. Blake Britton is a priest of the Diocese of Orlando, Florida, currently studying in the STL program at the Pontifical John Paul II Institute. He is author of the book Reclaiming Vatican II and a contributor to Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire Ministries.