In a world where digital technology has enabled an endless array of consumer goods and services to be ordered from almost anywhere and shipped to a doorstep in a matter of days, or even hours, all things “artisan,” “local,” “small-scale,” and “hand-crafted” have garnered quite a bit of mystique. Not only farmers’ markets and specialty craft fairs boast such goods—beaming photos of local farmers stare out over piles of produce in mainstream grocery stores, enticing buyers with small-scale wholesomeness. Online marketplaces like Etsy proffer every hand-woven, hand-painted, or hand-carved delicacy imaginable. Riding the waves of this trend are the practitioners of the four trades considered in Masters of Craft: Old Jobs in the New Urban Economy. They are whole-animal butchers working in elite urban food markets, highly skilled bartenders serving $20 cocktails, small-scale distillers bottling modern incarnations of moonshine liquor, and plaid-clad barbers at an über-trendy NYC shop. Author Richard E. Ocejo, a sociologist and academic based in New York City, spent countless hours observing, interviewing, and even learning these trades. The result is a well-researched and thorough, albeit very location- and culturally-specific case study of a few of the artisan crafts flourishing today.

In today’s economy, increasingly efficient production methods have led to an overwhelming turn towards cheaply made goods shipped from overseas factories in large quantities. Following a product from inception, to manufacture, to store shelf entails tracing a convoluted path, from the complicated international origins of component parts, to the multiple shipping methods required to distribute the product to consumers. Urban areas in the U.S. that were once centers of industrial production have become hubs for white-collar, technology-based companies whose employees are increasingly well-educated and increasingly tied to digital tools for the vast majority of their workday. Barbering, butchering, and the creation and distribution of alcoholic beverages don’t quite fit in with this new high-tech picture. These trades aren’t new at all; in fact, their long history as a part of civilized life for well over a thousand years led author Ocejo to term them “old jobs.” There are any number of old jobs that continue to be practiced today that could have been considered in a study such as this—farming, carpentry, or animal husbandry, for example—but Ocejo’s focus was on crafts that combined technical skill, a philosophical community surrounding the work and its product, and social interaction with consumers that allowed practitioners to share and/or teach their philosophy or skills in the public arena.

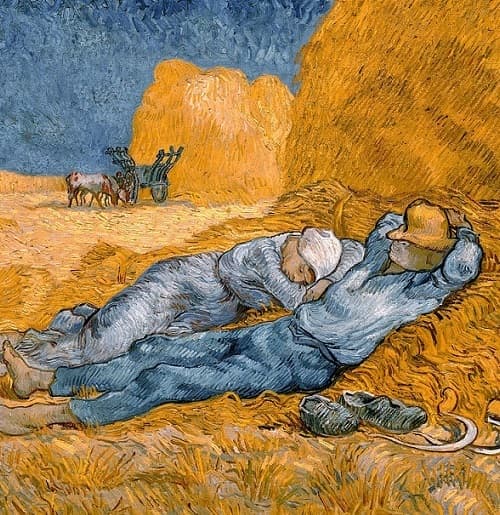

Barbering, butchering, distilling and bar-tendering, in their older incarnations, would once have been considered run-of-the-mill, working-class, manual labor trades. Ocejo describes them as “honest, respectable, and necessary, but low status, dirty, physically demanding, [and] for people with few other work options, not jobs people would want their children to do if they want them to move up in the world, and certainly not culturally hip” (xx). But in the elite urban social milieu where this study takes place, all these jobs are dubbed “trendy” and “hip.” Each of these crafts has been updated to fit their new urban niche, catering to affluent consumers. The bartenders featured in this book are the spiritual cousins of culinary-school trained chefs. They concoct unique mixed drinks with high-end, small-batch spirits in bars with an elite, refined crowd. Their methods are often old-school—for example, some saw or chip giant blocks of ice into small shavings for the drinks they serve, rather than using standard ice-machine ice, because this chills drinks quickly and with less dilution. Observing bartenders using techniques such as these, Ocejo remarks: “to them, efficiency through technology has decreased quality” (37). Small-scale distillers would agree—they are usually located in rural areas, employ only a few people, and are so small-scale they label and seal their bottles by hand using a pot of melted wax on a hot-plate. Yet their product is sought after and fetches high-end prices.

The butchers in Ocejo’s crosshairs, in their turn, leave behind factory-style slaughterhouses filled with grain-stuffed, feedlot animals, in favor of an earlier butchering style. Their small shops hearken back to the ethnic neighborhood butcher who specialized in culturally-specific methods of cutting down and using entire animals; today’s shops tend to draw an elite clientele interested in the grass-fed meats they feature, and is often willing to be tutored by the butchers themselves in different techniques for cooking cuts of the animal they’ve never tried.

Barbering, the one profession in this book outside of the food and beverage arena, was similarly reborn in a nostalgic reincarnation of the old neighborhood shop. New generation barbers are dressed casually, in jeans and plaid shirts, and the ambiance of the shop seems akin to a high-end hunting lodge. Just as barbershops were once hubs of socializing and camaraderie, the mainly male barbers banter with one another and engage the customers in their friendly discussion. Interestingly, the neighborhood feel of the barbershop of yesteryear couldn’t be recreated in the barbershop of today—today’s clients simply come for a fashionable, trendy haircut, and most if not all of them are strangers to one another. Only the rare client engages in the barbers’ chats.

All of the bartenders, barbers, butchers, and distillers—notably male-dominated crafts— featured in this study are men, many of whom live and work in trendy circles in New York City. Most are single—without wife, children or home mortgage to slow down or hinder their career flexibility. The majority of them come from a middle-class background and many of them attended college—some graduated, some tired of it, but almost all have some higher education under their belts. Many pursued unremarkable careers in the corporate or tech world, but found their work unsatisfying and unrewarding. Falling squarely in the midst of the postindustrial trend that considers one’s job not only as a cash-generator, but a path to happiness, they looked beyond the office, and found themselves in one of the four “old jobs.” Some were enticed by the tangibility of the product—in contrast to emails, spreadsheets, and distant results of paper-pushing, these barbers, butchers, distillers, and bartenders can see and touch (often with great immediacy) the result of their daily work. One barber, whose former career was in IT support for academic institutions, spoke with romantic nostalgia about blue-collar workers on car-manufacturing lines being able to actually line up and count the number of cars they had made that day. Pursuing these ancient crafts was often “the result of a search for meaning in work...an occupation to anchor their lives and provide them with purpose” (134). Many interviewed for this study considered their jobs more than just a way to make money; they considered their jobs to be a “calling”—one that often had to be justified to parents, friends, and onlookers who were skeptical of their change in profession and wondered why an otherwise successful individual would have chosen to pursue such a job when given other opportunities.

Even further, the fact that these trades enabled them to use both their body and their mind in a specifically skilled manner, in a predominantly male environment, gave each worker a unique chance to, in Ocejo’s words, “achieve a lost sense of middle-class, heterosexual masculinity” through their work (20). Interestingly, passionate, and close-knit communities of tradesmen and consumers, united by the shared skill set and philosophical and cultural significance of their craft, drew in many of the interviewed workers and kept them in their new-found jobs longer than many of them had anticipated. The bartenders attended conferences, seminars, and festivals celebrating cocktails. Barbers bantered with one another throughout the day, and shared tips for styling techniques; butchers were the knowledgeable guides for appreciative customers who were often unfamiliar with the specialty cuts of meat they encountered behind the counter in small, whole-animal shops. The distillers, usually working in more rural locations, were key players in their local economy, often forging ties with their agricultural neighbors by sourcing their raw ingredients from nearby farms.

Each one of these trades represents movements in the wider economy towards the admiration of, and demand for, skilled and local craftsmanship. The dynamic of investing both mind and body in the artful creation of a tangible product is something shared across the range of the old jobs seeing a renewal today. That being said, a casual reader may struggle with the specificity of the jobs considered here. They are so specific to their trendy, affluent urban niche that they may be less relevant or interesting to readers in other social circles. Barbers in male-fashion boutiques, pricey specialty cocktails, and tiny, choice cuts of the most select grass-fed meats are often far from the reality and reach of most consumers. A study that considered other “old jobs,” more based upon basic human needs for food and shelter, might appeal to a wider readership. Today’s economy has also seen a renewal in small-scale, family-run farms catering to locals and nearby urban residents via farmers’ markets and Community Supported Agriculture schemes; a casual survey of fairs and farm markets might find a number of carpenters, woodworkers, and other similar artisans who have chosen to pursue work with their hands even after completing a college degree.

Lastly, the absence of the family as an economic and social unit at play in the lives of individuals practicing these four “old jobs” is significant, and further limits the applicability of this book’s study. The lack of family ties is not really discussed beyond the fact—mentioned in passing—that having a family may have limited the flexibility of their career pursuits. Furthermore, the absence of the family in this study may give the impression that it is an institution which reduces one’s ability to pursue meaning and satisfaction in a career, and which may force individuals to engage in more mainstream, stable, and less personally-rewarding careers. A study which branched out to consider those artisan trades which serve more basic human needs—e.g., small-scale farming, animal husbandry, woodworking—may have discovered a different dynamic. In these cases, the family may actually create incentives for stability, efficiency, cleanliness, and productivity. A casual survey of these more basic trades might find that they attract individuals with families, even families of significant size—an important reminder when pondering the relatively tunnel-like vision of Masters of Craft—illustrating that the family does not necessarily force individuals to compromise their pursuit of meaningful work.

Carla Galdo, a graduate of the John Paul II Institute, lives with her husband, four sons and daughter in Lovettsville, Virginia.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, A Return to Awe.