We have to become saints, as they say in my part of the world, ‘down to the last whisker.’

—St. Josemaría Escrivá, Friends of God, “The Richness of Ordinary Life” (5)

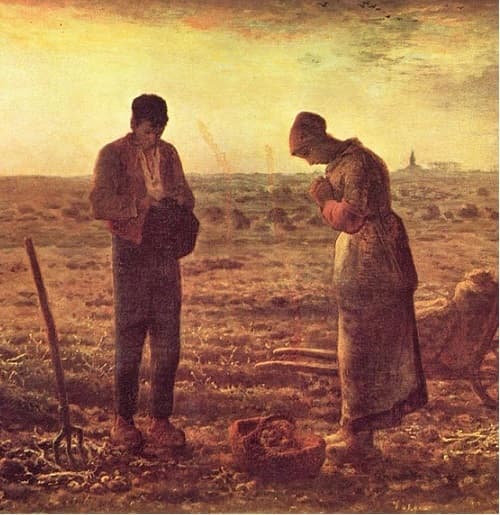

Why in the world would the Word of God leap down from Heaven, become incarnate, enter time and space—only to spend a good thirty years devoted to the most prosaic of pursuits? Rather than bursting forth fully formed and accomplishing our Redemption in a more efficient manner, He appears as an infant, then grows to adulthood as gradually as anybody else. Then He toils away as a manual laborer for nearly all His remaining years on earth. Is this any way to run an Incarnation? Why so much wasted time? It’s enough to make a person suspect that everyday life and ordinary work might have some mysterious, hidden significance.

And so they do.

That’s the leitmotif of this collection of homilies by St. Josemaría Escrivá, founder of Opus Dei, canonized in 2002 by St. John Paul II, who christened him “the saint of ordinary life.” As St. Josemaría contends in a key 1967 homily entitled “Passionately Loving the World”:

There is something holy, something divine, hidden in the most ordinary situations, and it is up to each one of you to discover it.… We cannot lead a double life. We cannot be like schizophrenics.… There is just one life, made of flesh and spirit.…. We discover the invisible God in the most visible and material things.

And:

Either we learn to find our Lord in ordinary, everyday life, or else we shall never find Him.

Two essential terms in St. Josemaría’s writings—“work” and “vocation”—need to be understood in a broader-than-usual sense. First, “work” is not to be reduced to either paid employment or manual labor. In fact, the word functions as shorthand for “everyday activity”—all the minutiae of the duties entailed by one’s state of life. Volunteering at the soup kitchen, preparing an Excel sheet for the boss, filling out an insurance form, defrosting the meat for supper—all this is bona fide, sanctifiable work, just as surely as a carpenter sawing a board, a monk illuminating a manuscript, or a priest composing a homily.

Second, “vocation” is not an extraordinary calling addressed to a select few, those chosen to pursue priestly ordination or religious vows. And this is not mere semantics. As the Second Vatican Council made clear in Lumen gentium, the “universal call to holiness” is just that: directed every bit as much to the laity as to clergy and religious. No detraction from the nobility of vowed life is implied in acknowledging that all Christians are genuinely called to lives of personal sanctity and intense apostolate, whether they ever leave the lay state or not. “The holiness we should be striving for,” St. Josemaría insists, “is not a second-class sanctity. There is no such thing” (Friends of God, 6).

In other words, not only will the “raw material” of our sanctification consist (usually) of unglamorous, ordinary activities; the vast majority of Christians are called to be ordinary people, too—lay men and women, with no distinctive habits, no vows, no dramatic renunciation of the workaday world. And, yet, we are all called to pursue union with Christ with the utmost dedication:

Christ’s invitation to sanctity, which he addresses to all men without exception, puts each one of us under an obligation to cultivate our interior life and to struggle daily to practice the Christian virtues; and not just in any way whatsoever, nor in a way which is above average or even excellent. No, we must strive to the point of heroism, in the strictest and most exacting sense of the word. (3)

The standard is staggeringly high, but so too are the stakes:

We are in a position to give him, or deny him, the glory that is his due as the Author of everything that exists. (24)

Is this something revolutionary? Yes and no. The call to invite the Holy One of Israel into every nook and cranny of one’s life is as old as the Shema (“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your might…”). Nothing indicates that He was addressing Himself exclusively to a “spiritual elite.” Nor did the early Church make any provision for first- and second-class sanctity. But as priesthood and monastic life grew more formally structured and more deeply integrated into Christendom, a certain clericalism—a certain notion of two separate sets of standards (one for the religious and another for the rest of us)—crept in as well. Laypeople were to “pay, pray, and obey”; at most, they were to function as the long arm of the clergy, contributing time, money and prayers to projects designed and directed by the ordained. They were not expected to strive for heroism; they were not thought to possess legitimate autonomy. In fact, they were deemed to have declared themselves less than wholeheartedly dedicated to Christian life: after all, they had remained “in the world” rather than renouncing it. Against this backdrop, St. Josemaría’s ideas were indeed revolutionary: he was even accused of heresy.

The homilies in Friends of God don’t merely make the point that ordinary activities are “the very hinge on which our sanctity turns” and “offer us constant opportunities of meeting God, and of praising and glorifying him through our intellectual or manual work” (81). They also get down to the nitty-gritty of how it’s done.

For example, there’s a chapter on detachment, which amounts to a different kind of renunciation of the world, though not as obvious, not ratified in a single moment.

Our Lord asks for generous hearts that are truly detached. We will achieve this if we resolutely cut the thick bonds or the subtle threads that tie us to ourselves. I won’t hide from you the fact that this entails a constant struggle, overriding our own intelligence and will, a renunciation which, frankly, is more difficult than the giving up of the most prized material possessions. (115)

He also sheds light on why work is so decisive:

[B]y doing your daily work well and responsibly, not only will you be supporting yourselves financially, you will also be contributing in a very direct way to the development of society, you will be relieving the burdens of others and maintaining countless welfare projects, both local and international, on behalf of less privileged individuals and countries. (120)

(Together with other illuminating passages, this one has been incorporated into a series of prayers that make up a novena for work through St. Josemaría’s intercession.)

And besides these “external” consequences of work, there’s the question of the self-realization of the personal subject. As St. John Paul II would elaborate years later, work is where human persons—not least the laity—take up their God-given freedom and their legitimate autonomy to perform the actions that not only keep the external world running but also cause us to flourish or deteriorate as subjects. In St. Josemaría’s terminology, we not only sanctify the work itself; we sanctify ourselves—and others as well—through our work.

Our daily to-do list is not just a series of tasks to be checked off as hastily as possible, the better to get on with more noble, more “spiritual” things. We’re not just called to busywork; it’s not just that “idle hands are the devil’s plaything,” or that drudgery builds character. Nor are we trying to “work our way to heaven,” since “without [Him] we can do nothing” (John 15:5). Nor—St. Josemaría insists most firmly—is work a curse, though the “sweat of the brow” that has attended it ever since the Fall certainly is.

Because the world comes from the hands of God, it is primordially good. Because He left it intentionally “unfinished”—in need of cultivation and development—our work has always had its part to play. And because it’s been corrupted, though not entirely ruined, by original sin, our work is doubly necessary. God has graciously allowed us to play a part not only in the “cultivation” of creation but in its co-redemption. Together with Him, we embrace its primordial goodness while working to rescue it, and ourselves, from the stain of original sin. Through our work, we seek to let that original goodness shine forth again. Rather than becoming worldly, we are to be—in one of St. Josemaría’s signature phrases—“contemplatives in the middle of the world.”[1]

Our task is not to fear, reject, or flee the world but—always in union with Christ—painstakingly to restore it in a million seemingly insignificant ways. That is what work is for.

No act of love is too small or too mundane for a God who has numbered the hairs of our head. Becoming saints “down to the last whisker” turns out simply to be an accurate account of our mission.

Devra Torres, a mother of eight and a writer, editor and translator, blogs weekly at The Personalist Project.

[1] Josemaría Escrivá, Furrow (Scepter Publishers, 1992), 497.