You may wonder, do we really need another saint book? Didn’t the good Fr. Lovasik say everything in his 101 titles of the Saint Joseph Picture Book Series?

Too often images of saints for young and very young children are “flat and friendly,” digitally produced and barely differentiated. A familiar example are the banal illustrations of MagnifiKid. Though the written content of the publication runs from decent to excellent, its illustrations are easy-to-ignore images, which leave the viewer wishing for greater insight into character and meaning.

Many illustrations of saints simply lack technical skill and demonstrate a failure to apply the elements of art to their creation. Or they rely on modern “visual tropes,” such as making the images of saints approximate the oversize-eyed characters popularized by TV and movie marketing. The Boy Who Became Pope

written and illustrated by Fabiola Garza attempts to win over children in this way. An ironic and grave flaw in our children’s picture books is so often the pictures, which don’t symbolize or point to anything.

Depictions of the saints must, in written and artistic form, invite children to “escape into the real.” The words and illustrations must not just convey information but a proposal that “Christ takes absolutely nothing of what makes life free, beautiful and great…and he gives you everything” (Pope Benedict XVI). Too many saint books fail to live out this proposal either through lackluster writing or tame illustration.

Reality is already approachable, multidimensional, and highly attractive. ... Children want to know the world as it is and that this seeking to know things for what they are includes saints.

Stories of the Saints by Carey Wallace and illustrated by Nick Thornborrow is an exception. It offers the most incisive writing regarding the saints. Wallace writes a gripping introduction (who else can claim their introduction is gripping?), asking “Who are the saints?” and “Are these stories true?” and even proposes that the lives of the saints imply a response from us.

Saints aren’t people who are always good and never afraid. They’re people who believe there must be more to life than just what we can see. This world may be hard and unfair, but saints believe in a God who is bigger than the world, whose law is love… They tell us that when people stand up for justice or mercy or love, they may see miracles, but they may find themselves in mortal danger. Or both.

Wallace’s writing is powerful, direct, and insightful. Thornborrow’s illustrations dare a great deal and are less reliably good; some illustrations are interesting, some are odd, and others look vaguely evil. As a video game designer, Thornborrow appreciates heroism, but he is hardly steeped in the Christian visual tradition. Consequently, his outside-the-box interpretations can be either insightful (St. Sebastian) or ugly and bizarre (St. Augustine, St. John Vianney). Even a book as appealing as Wallace’s has a significant limitation.

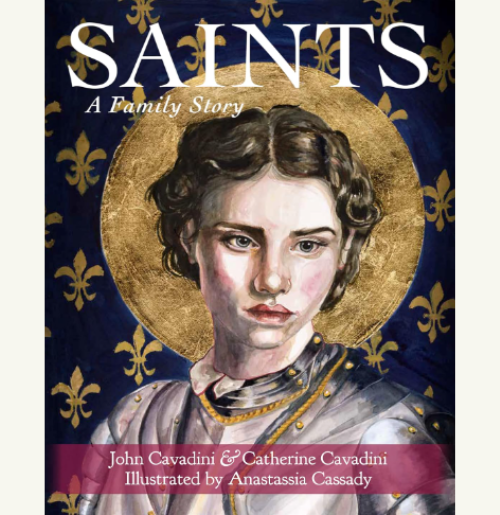

So, do we need more picture books on the saints, then? Saints: A Family Story written by John and Catherine Cavadini (a father-daughter author team) and illustrated by Anastassia Cassady offers a uniquely excellent response. We need more saint stories if they demonstrate the intelligence and craft, human insight, age-appropriate detail, challenge-level conversation opportunities, and loving and gifted artwork evident in the Cavadini-Cassady effort.

Often what is most surprising about Cassady’s illustrations is how fitting they are, while still full of novelty. For example, at first glance the illustration of St. Joseph could seem to be another St. Joseph-the-Worker stained glass window, like a hundred others. But immediately the viewer notices something different: the illustration is partly like stained glass, partly like an icon, but with such a friendly expression, as if Joseph looked up from his carpentry in mid-swing to notice you standing in his workshop. As a man of piercing intensity, John the Baptist is hard to capture. Cassady shows him looking wild, his hair stringy and blown back, but his eyes calmly focused and entirely sane.

Cassady makes use of traditional iconography but uses it in occasionally unexpected ways. For the image of St. Augustine, the figure is painted and the background is mosaic; he holds a pear in his right hand while in his left he holds the text of Romans 13:13 in Latin: “As in a day we walk honestly, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarreling and jealousy,” with the first letters of the book’s facing page implying the next stage of St. Augustine’s life, when he would “[i]nstead, put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires.” Cassady cares enough to include it, as an untranslated Easter egg for the curious (or educated) reader.

St. Monica is depicted as a youthful, beautiful, serious North African woman, ornamented with chandelier earrings along with a golden halo. Cassady often takes up a medium or style that is native to the saint’s place, such as depicting Rose of Lima with a colorful Peruvian serape and braids as well as her image on Peruvian currency. Servant of God Takashi Nagai is depicted in a traditional Japanese painting style (nihonga or kanō).

To put a saint into his own visual-symbolic cultural context is illuminating, when so many other crafters illustrate saints in cartoonish, flat, simplistic ways in order to make them “approachable” for children. The Cavadinis and Cassady understand that reality is already approachable, multidimensional, and highly attractive. They understand that children want to know the world as it is and that this seeking to know things for what they are includes saints.

Regarding the written content of Saints, the Cavadinis’ narrative on the saints is conditioned by two seemingly opposite poles—thorough academic research and a thorough understanding of children. John Cavadini and Catherine Cavadini are professors of theology at the University of Notre Dame, so it is not unusual that they have a mastery of the available data. Yet, as a grandfather and a mother, they also possess a mastery for disclosing the marvelous and humble meaning of each saint’s life in terms that awaken wonder, attraction, and imitation. If you were going to research a saint and tell your child or grandchild in your own words about the saint’s life and charism, your telling would likely have the warm tone of Saints: A Family Story. Hopefully, it would also have its depth and texture. The Cavadinis do not allow even saints like St. Monica or St. Francis to be flattened into the standard labels of “weepy” and “animal-lover.” And they use rich literary sources, such as Sigrid Undset’s biography of Catherine of Siena, as material for their narrative. In fact, I prefer their telling to Undset’s, which seems to portray Catherine as always-nearly-perfect and renders her unbelievable and inscrutable. One sentence in particular breaks open the life of St. Catherine in a way that the more hagiographical Undset never did: “All of these acts of love gave Catherine the courage to speak to important people who were making terrible mistakes, because she knew that when she was telling them to reform and make better decisions, she would be saying it out of love.”

Occasionally, in its effort to be conversational, the writing is clumsy and lacks lucidity. In the narrative on the life of Venerable Augustus Tolton, the first Black Catholic priest ordained in the United States, the Cavadinis struggle to interweave smoothly and consistently an analogy about struggle, raging rivers, stormy seas, and all people being in the barque of the Church. In a rare case, the lack of coherence and focus is more striking: In the biography of St. Gianna Molla, the narrative moves backward, forward, and back again in time, referencing the testimony of St. Gianna’s husband Pietro and requiring young readers to employ several layers of abstract thinking regarding time, relationships, and the canonization process. Among sundry beautiful points the authors intent is that St. Gianna shows how “even your mom could become a saint,” but this point is made too obliquely and without concrete reference to the details of St. Gianna’s life. The authors appear to be undecided regarding which aspects of St. Gianna’s life they want to highlight.

Despite the occasional lack of written clarity, the warmth of the Cavadinis’ narrative and Cassady’s artistic agility adapted to each saint render Saints: A Family Story a uniquely unified book. It is altogether the best saint book currently available, conveying in word and picture that “it is Jesus you seek when you dream of happiness; He is the beauty to which you are so attracted; it is He who provoked you with that thirst for fullness that will not let you settle for compromise” (Pope St. John Paul II).