Patrick Coffin’s approachable and engaging text, The Contraception Deception, is written not to develop new teaching, but to present the teaching of the Church to the broader culture. The text would also serve the educator well for use in the classroom. Coffin writes in language accessible to most undergraduates, with an organization that can be followed easily.

For those who struggle with the Church’s teaching, or who reject it entirely, or who accept it but cannot articulate it, Coffin insists on the importance not only of the mind, but—perhaps even more so—of the will and the heart. “In this delicate arena [of Catholic sexual morality], intellectual arguments alone are generally useless in the persuasion department.” One could say that in this arena, conviction requires conversion. Coffin thus concludes many of his chapters with short prayers, to personalize what could otherwise be a mere academic exercise.

His first two chapters are historical, exploring how certain portions of the Christian world quite recently came to accept contraception as acceptable or even good, and how he himself came to recognize it as evil. Culturally and spiritually, he argues, the acceptance of contraception brought with it the worship of the “false god” of the “sterilized orgasm,” which steers the life-giving and unifying action of sexual intercourse away from the Author of life as it closes the couple off from the complete gift of self to the other.

The third chapter was, for me, the most surprising. I’ve taught Humanae vitae a great number of times; but paragraphs 4‒6, which proclaim the authority of the Church to teach the requirements of the Natural Law, are not paragraphs that I have ever focused on, let alone made the starting point of an exploration of the teaching. People should become convinced that the Church teaches what it does about sexuality because it is true, not that it is true because the Church says it. But for Coffin, the whole crisis over the acceptance of the Church’s teachings on sexual morality is not at root a crisis about the Church; it is a crisis of accepting. The order inscribed in human sexuality is not something that is up for majority vote, determinable by consensus; it’s an essential characteristic of our being, which is a gift from God. And because it is a gift, is it something that must be received to be lived.

Responding to the objection that Scripture is silent when it comes to contraception, Coffin’s fourth chapter shows, first, that there are specific instances in which the Bible decisively condemns actions which can only be understood as “contraceptive.” More than that, however, this chapter’s main purpose is to lay out the worldview of the Bible, in light of which the abhorrence of contraception should clearly follow. With Scriptural passages that are abundantly and masterfully presented, Coffin shows how Scripture thinks “maximally,” not “minimally,” about the good of children, who are a blessing and whose ultimate Source is God.

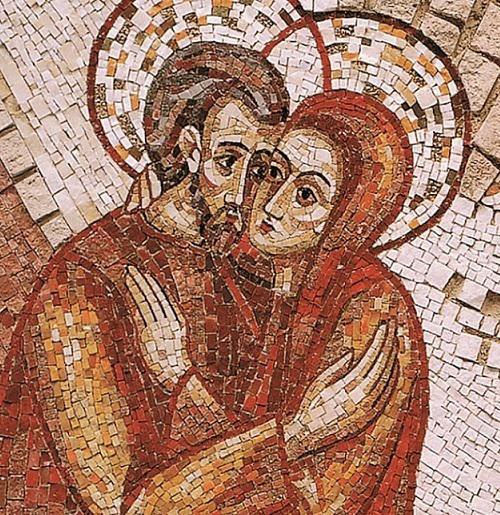

Chapter five considers the ultimate theological grounding of the Church’s teaching on contraception by arguing that human beings are called to love in a way that images God (Gen 1:26‒27), Who is a Trinity of Persons. In its physicality—and not in spite of it—the sexual union of husband and wife is an intimate sharing in the creative power of the supreme Author of life. For this reason, Coffin refers to sexual union as a “natural holy of holies” in which God’s presence dwells. Because of the sacredness of human sexuality, contraceptive acts are particularly evil. Indeed, he considers them a kind of idolatry. Why would this be the case? It is because in any human action, “pleasure” can never be the goal (the “end” or purpose, in the language of moral theology). Rather, human action must be directed towards a “good,” which, when attained, then brings pleasure or joy. The pleasure that the husband and wife experience during the authentic gift of self is good precisely because it comes as a result of giving themselves. But contraception makes it impossible to give themselves completely, which by default makes pleasure the “end” of their action. Thus, if the true gift of self in marital union is a kind of imaging and worship of the Trinitarian God, the contraception becomes “the main liturgical action of worship of the false god” of our times.

The theological foundation and liturgical implications of contraception can be viewed Christologically, as well. Citing Augustine, who spoke of the Cross as the “marriage bed” of Christ on which His act of total self-giving effected new life for His bride, the Church, Coffin asks, “What kind of grotesque sacrilege would contraception signify? It would be Jesus ensuring in secret that His death on the cross was faked, that it did not really save us.”

Marital love, in sum, is governed by the Trinitarian and Christological “law” of self-gift. And failure to live according to this truth has natural consequences: “a harvest of impotence, sub-replacement population levels, and a high divorce rate.” Upon this theological foundation Coffin builds his treatment of the philosophical concept at the heart of the Church’s condemnation of contraception: the Natural Law.

Behind the widespread dissent of so many theologians on sexual morality lies a rejection of the very notion of the Natural Law. Coffin does a fine job discussing the main philosophical causes of this dissent, but also recognizes that the roots of this dissent (e.g., the “indifferent” will of Ockham’s voluntarism, the Cartesian body as “pure extension,” etc.) have sunk so deeply into our worldview that they are hardly noticed. His defense of the Natural Law is particularly aware of this. But it also reaches surprisingly, into Scriptural territory, laying out the worldview contained in the Bible, especially its view of the human person as a unity of body and soul, and the sacrality of the body, which is spoken of in Scripture as a “temple.”

In light of the Natural Law, knowable through the voice of conscience, we are directed through the ordering of our nature to our ultimate perfection in the love of God. Coffin’s treatment of conscience is orthodox, yet brief. More than the meaning of conscience itself, he emphasizes the need for caution when appealing to this “inner room” in which the voice of God is meant to be heard. Conscience, he rightly warns, is not infallible, and the Natural Law needs the authority of the Church to be interpreted rightly. Nevertheless, some more space here could be given to developing a better overview of conscience itself. I can imagine some readers wondering what, precisely, conscience is, and why I should trust it if it is so wounded and needs so much help.

Little needs to be said here regarding his chapter discussing the claim that a “population explosion” threatens the planet. Against such a view, he offers a number of fascinating and compelling statistics, suggesting that not only is our planet more than capable of sustaining the present population, but also that we are facing immanent societal crises because of a collapsing birthrate. Of greater interest are the final three chapters, treating, respectively, surgical sterilization, assisted reproductive technologies, and the moral difference between Natural Family Planning and artificial birth control.

What should a couple do if they come to realize that a past sterilization procedure was wrong? How do they “repent,” if repentance means turning away from one’s sin and refusing to continue to “benefit” from it any longer; but they are unable to undo the procedure for medical or financial reasons? Coffin offers some prudent advice: Prayerfully consider whether a sterilization reversal is possible or feasible in one’s own situation. If so, undergo such a procedure, and welcome what children God may bless one with; if not, consider practicing periodic continence as if the procedure had not happened, so that the virtue that such discipline makes possible might also bless one’s marriage.

Most helpful in my view were the questions that Coffin suggests we might raise to a person who confides in us that he or she has undergone sterilization. Is their marriage really stronger after the sterilization? Did they consider the possibility that someday their financial situation might be better and that they might want to welcome more children into their family? Did they consider the possibility that their current spouse might die and that they would then enter any second marriage unable to give that new spouse the gift of children? Such questions are meant gently to help the person begin to face the full reality of what has been done.

While Coffin’s penultimate chapter is not directed towards contraception directly, it does treat of an issue that is built upon the same logic: the emergence of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs). If the two meanings of the sexual act are separable, he shows, then both contraception and ARTs follow. This chapter stands as an accessible introduction to those aspects of medical ethics relating to procreation, explaining some of the most common forms of ARTs, and why the Church teaches that they are immoral. In addition, it summarizes the basic tenets of Catholic medical ethics, such as the teaching that medicine should assist the natural order in achieving its ends, rather than replacing the natural order.

As with contraception, Coffin correctly identifies what exactly is wrong with assisted reproductive technologies: not the end of achieving a pregnancy, but the means employed to achieve that end. And the means, especially at present, have terrible consequences, particularly the discarding of “extra” embryos or the post-implantation abortion of “excess multiples.” One could object that such atrocities are caused by the inherent limitations of present techniques. But Coffin recognizes that the evil of ARTs that replace the natural order lies in the logic of the technology itself: the failure to receive the child as a gift. Children have a right to originate from a conjugal union.

In his chapter on Natural Law, Coffin had mentioned briefly the misapplication of the so-called “principle of totality,” to which Humanae vitae alludes in nos. 3 and 17. Every sexual act, the Church teaches, must be “ordained in itself to bring forth new human life.” Yet many who believe themselves to be faithful Catholics are under the impression that their contracepted sexual acts don’t represent “closure” to new life, because these couples do, in fact, desire children in their marriages—just not at the present time. In the Natural Law chapter, Coffin had largely left unaddressed the question of why individual marital acts must remain ordained in themselves to new life, and not simply their marriage as a totality. His final chapter, however, provides that answer.

By using a series of analogies (dieting, speaking, praying, protesting, wedding planning), Coffin is able to show how the evil of contraception is located within the act itself, and not in the intention, or circumstances; and this, without ever invoking the technical language of the “sources” of the morality of an action. A further point that I found particularly commendable is that, although he uses the language of the “contraceptive mentality,” he never once implies that one’s “mentality” (or intention) can turn NFP into contraception. In other words, he recognizes that these are two fundamentally different types of moral actions, and that their “species” is not determinable by the mindset of the agents.

Coffin writes with the authority of one who has struggled with the question of contraception personally, and who has long experience presenting the teachings of the Church to audiences who may or may not be deeply theologically formed. Yet he can hardly be said to remain in the theological shallows. Indeed, Coffin brought to mind Josef Pieper’s praise for Aquinas, who, as a teacher, “sees reality just as the beginner can see it, with all the innocence of a first encounter, and yet at the same time with the matured powers of comprehension and penetration that the cultivated mind possesses.”[1]

[1] Guide to Thomas Aquinas, trans. Richard and Clara Winston (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), 95. Emphasis in original.

William Hamant is Assistant Professor of Theology at DeSales University.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Hitched Versus Hooking Up.