Daniel J. and Hartzell Siegel,

Parenting from the Inside Out: How a Deeper Self-Understanding can Help You Raise Children Who Thrive

(Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2004).

Daniel J. and Bryson Siegel,

The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture your Child's Developing Mind

(Bantam Books, 2012).

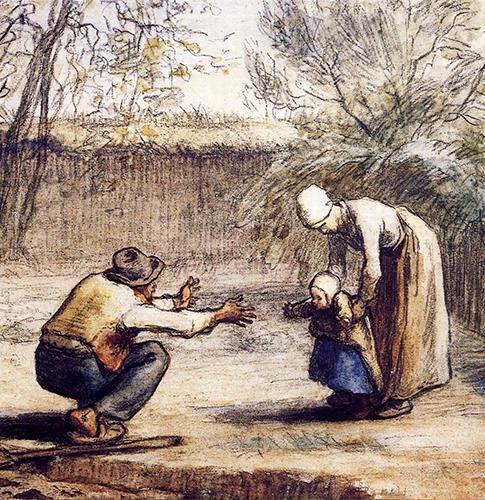

John Bowlby’s articulation of attachment theory in the second half of the 20th century, bolstered by Mary Ainsworth’s empirical work, represents a seminal development in the field of psychology, undeniably depicting the fundamentally relational nature of the human being. Fast forward a few decades from the birth of attachment theory and we find a cross-disciplinary field termed interpersonal neurobiology, which weds attachment with neuroscience. The human brain, we learn, is not only wired for interpersonal relationships but is also in need of them for healthy development. Thus both psychological and neurological findings, in tandem, show that the child needs contingent, attuned, and responsive interaction with their parents to grow in self-awareness, empathy, emotional regulation, and various other human capacities. A stable and healthy sense of self cannot develop in a vacuum, but only in the context of secure attachments. Indeed, being made in and for communion is manifest at all levels of the human person: we come to know, understand, and possess ourselves only through loving and affirming relationships.

The person is made by and for an Other—God—and what is most deep and essential in a child is not his brain but his heart, in the biblical sense of the term. Each child comes into the world with a need for love, happiness, and meaning which is not a mere epiphenomenon of brain activity, but an image of the divine, of the One who fulfills these needs.

The primary educators of children, mothers and fathers, can learn much from the fruits of attachment theory and interpersonal neurobiology conveyed in these two books by Daniel Siegel and his colleagues: Parenting from the Inside Out and The Whole-Brain Child. They contain many accessible examples of how parent-child interaction and education impact on brain function in the developing child. In Parenting from the Inside Out, Siegel and Mary Hartzell draw from attachment research to depict how a parent’s early life, self-understanding, and attachment narrative shape the bond a child forms with him or her. Parents learn about the importance of being mindful of their own mental states and of tuning in to the child’s subjective experiences. This combination of self-reflection and active attunement to the child sets the context for secure attachment bonds to form, which in turn have positive repercussions for a child’s developmental trajectory. The book offers practical tips and exercises for communicating constructively, processing difficult experiences with children, and repairing after ruptures. The authors recognize, however, that being a mother or father involves more than the application of skills: it entails the communication of oneself and a receptive posture before one’s child. Though not stated in these terms, the parent is encouraged to welcome the other by honoring the unique inner life of his son or daughter, and learning to distinguish his own feelings and thoughts from those of his child. Careful self-reflection can help parents sort through wounds from their own early lives, thereby avoiding the intergenerational transmission of attachment trauma and insecurity. Thus, the book’s core message is a hopeful one:

We are not destined to repeat the patterns of the past because we can earn our security as an adult by making sense of our life experiences. In this way, those of us who have had difficult early life experiences can create coherence by making sense of the past and understanding its impact on the present and how it shapes our interactions with our children (248).

While Parenting from the Inside Out offers an accessible introduction to various findings in neuroscience, the focus on brain development is more prominent in The Whole-Brain Child. In this book, Siegel and Tina Payne Bryson suggest that parents often learn a great deal about their children’s bodies—what to feed them, what bodily temperature constitutes a fever, and so on—but tend not to know much about children's brains. In authoring this book, they seek to fill that gap, providing “12 revolutionary strategies” to nurture children’s minds founded upon neurological principles. Integration is the conceptual thread that runs throughout the book, with strategies offered to facilitate integration of the brain hemispheres, the lower and higher parts of the brain, aspects of memory, parts of the self, and the self with the other. First we learn about horizontal integration, which unites the “logical, literal, linguistic, and linear” left brain and the “intuitive, holistic, emotionally attuned” right brain. In order to facilitate integrative functioning of the two brain hemispheres, parents are provided with a strategy to “connect and redirect” when children’s emotions run high. Parents learn to connect with their distressed children using right-brain to right-brain communication, tuning in to the child’s emotional state and expressing this through nonverbal means (e.g., tone of voice, body language, facial expression) and verbal empathy. In a heightened state of distress or frustration, the child will not initially be responsive to left-brain logical reasoning. However, after experiencing the parent’s connection, his left brain can often “join the conversation.” The child will be more able to take in explanations and reasons once he has been soothed through parental connection in a right-brain mode, at which point he can be “redirected” to reasons and explanations. This and other strategies have a practical utility and honor the developmental reality of the child.

A proper understanding of the child’s brain can certainly equip parents to educate their children better. At the same time, it is not the child’s brain that seeks understanding, learns, wonders, hopes, and loves; it is the child who does all of this; and it is not the brain of the child that is the object of parental education. It is misleading, therefore when we read in The Whole-Brain Child that “the drive to understand why things happen to us is so strong that the brain will continue to try making sense of an experience until it succeeds” (29). Knowledge of a part of the brain needs to be situated within a unitary understanding of the whole, namely, the child as a person-in-relation. The brain is fascinating because it is a manifestion of the person, which is not reduced to nor “explained” by it.

The person is made by and for an Other—God—and what is most deep and essential in a child is not his brain but his heart, in the biblical sense of the term. Each child comes into the world with a need for love, happiness, and meaning which is not a mere epiphenomenon of brain activity, but an image of the divine, of the One who fulfills these needs. It is certainly in accord with the dignity of the child to be validated, affirmed, and understood in the ways described in these books; however, if parents remain at the level of a brain-based perspective, they will fail to educate the whole child. Saint Paul taught us to “Test everything and retain what is good” (1 Thessalonians 5:21), and indeed there is much that is good and worth retaining in these books. Parents need to discover more about themselves in relation to their children, but more than this, they need to be in a state of wonder before the great desires and questions that constitute each child.

Margaret Laracy is a clinical psychologist in private practice and assistant professor at the Institute for the Psychological Sciences in Arlington, VA.