Carlo Collodi, Pinocchio with Reflections on a Father’s Love by Franco Nembrini (Well-Read Mom and Wiseblood Books, 2024).

The first time I went birdwatching with an avid birding enthusiast, my guidebook-knowledge transformed into an experience of joy and contemplation. A robin was no longer a familiar bird flittering in my backyard. I could distinguish it now by its song of rippling notes and clear, syllabic whistles. But it wasn’t an ornithologist who helped me notice these subtleties, simply a person in awe of birds who helped refine my senses.

In the new edition of Pinocchio—a collaboration between Well-Read Mom and Wiseblood Books—something similar happens where the awe of the guide percolates into our own sensibility. This edition weaves the original story with commentary by the Italian writer, teacher, and Dante expert Franco Nembrini. Whereas previous editions approach the story through a socio-political lens, Nembrini recovers the validity of understanding stories through our human experience—specifically, our relationship to God and the Church. Early on he clarifies the aim of his commentary: “The crucial thing is not to put words in Collodi’s mouth, but rather to explain what happens to you when you read.” Understanding this point is key to appreciating his reflections: Sometimes experience more than explanations can bring to light questions that reach “the most profound need of each and every human being” at the heart of a story. Nembrini challenges us to share in the delight of a story that has profoundly impacted his mind and soul and emboldened his Christian imagination.

The Worldview of Pinocchio

Nembrini’s reflections examine Collodi’s life while working through the tensions between Collodi’s poetic vision and his culture. In the world of literary criticism, there are many ways to read a story. From cultural studies to critical race theory and from formalism to deconstruction, literary theories challenge our understanding of a story and work to convince readers of a new perspective. Many of these theories, however, leverage dominant social views and dismiss the transcendent and theological dimensions of a story—the dimensions that speak to us as embodied human persons who read for joy and wisdom. Nembrini’s reflections take the Catholic worldview of Collodi’s Italy seriously. He shows readers that attending to the Catholic worldview of a story ushers us into the depths of human mystery.

Nembrini’s commentary consists in interweaving personal reflections with literary criticism that pays close attention to the Catholic worldview that shaped Pinocchio. In Gene Edward Veith Jr.’s essay “Reading and Writing Worldviews,” he explains the importance of what he calls “worldview criticism” for a Christian reader. “Worldview criticism” allows readers to see particular stories as charged with a theological depth. Drawing on C. S. Lewis, Veith argues that if the key value of literature is entry into “other worlds,” then “[r]eading with worldviews in mind—both one’s own and that projected by the text—allows Christians to engage works in their own terms while also interacting with them theologically. … On its simplest level, worldview criticism … involves the ancient spiritual discipline of discernment.”[1] This entry into “other worlds” gives readers access points to truth that literary criticism alone often precludes.

However, Collodi’s readers insisted that he finish the story in a different way. In other words, his readers wanted redemption.

When Nembrini mines Pinocchio for a moral meaning connected to its anagogical and allegorical significance, he delivers treasures that are particularly awe-inspiring. For instance, in his reflections on Jiminy Cricket, Nembrini notes that the role of Pinocchio’s conscientious companion is often regarded as a moralistic expression of a duty to choose right in order to avoid consequences administered by an authority: “Woe to those boys who rebel against their parents, and run away capriciously from home. They will never come to any good in the world, and sooner or later they will repent bitterly.”[2] Nembrini, however, understands the cricket’s words to Pinocchio to mean: “They will never know any true goodness, anything of the goodness of life. They will never know anything of what it truly means to love or rejoice or suffer. … Goodness is to know these things.”[3] Morality, in other words, is not based in a Kantian ethics of duty but is a transcendent pursuit of the good life. Nembrini sees Jiminy Cricket as “the human heart” and “the divine imprint” who echoes the truth of the mystery of creation. This view moves us into the real adventure at stake: being transformed in our relationship with God the Father.

This idea of worldview criticism also helps us to see how Nembrini’s reflections on a father’s love become a heuristic for realizing the spiritual beauty of the story. These reflections provide a stark contrast to literary criticism that flattens the story with post-Christian themes of social power. For instance, when Geppetto makes Pinocchio new feet after Pinocchio has burned them, Nembrini reflects on theodicy—how to reconcile God’s love for us and the beauty of the world with suffering. These kinds of reflections are woven between each chapter of the story, transforming the story’s texture into something much richer than what annotations alone can provide.

The Christian Pattern of Pinocchio

Art shapes our social imaginations through our experience of common images and stories. For many of us, our first experience of Pinocchio consists in the 1940 animated Disney version. This version focuses on Pinocchio’s lying at the expense of staying true to the actual nineteenth-century story and its form. The opening line alerts us to a familiar Christian pattern:

There was once upon a time . . .

“A king!” my little readers will instantly exclaim.

No, children, you are wrong. There was once upon a time a piece of wood.

While some critics have read this opening line as a subversion of the fairytale, Nembrini points us to how Collodi’s turn on the classic fairytale opening takes us from question of origins (Where do our stories come from? What came first in the beginning?) to existential questions of human experience. To answer the existential questions, reality must come first, Nembrini argues. The reality for Master Cherry, the first character we meet, is a piece of wood. When seen in light of these questions, Pinocchio’s lying is not so much a failure of duty as it compromises the reality of his inchoate soul.

The temptations, obstacles, and vices that Pinocchio must grapple with point to the Fall. Through his stumbling, we ask questions that all human persons struggle to reconcile and understand: Why is there tragedy, suffering, and violence in the world? How do we live knowing it exists? The story initially ended with Pinocchio paying the price for his choices by being hanged from the Big Oak tree and dying. However, Collodi’s readers insisted that he finish the story in a different way. In other words, his readers wanted redemption.

Collodi’s readers seemed to see an essential inconsistency with the Christian pattern of the story. Asking for a new ending, his readers were asking questions of redemption: How do we atone for our mistakes? How does grace operate in the world? How do we embrace our freedom and flourish as fully human? Nembrini finds the answers in Collodi’s choice to give the Blue Fairy a salvific role like Dante’s Beatrice. By characterizing the Blue Fairy as “the beautiful Child with the blue hair,” Collodi creates an analogy between the Fairy and Mary and the Church. While Collodi may not have consciously written a Christian paradigm for his story, a Christian paradigm pulsed through the story’s veins.

Some might wonder if Nembrini stretches his reading too far given that the story lacks reference to God and religion. Collodi was also a member of a political and intellectual movement in the mid-1880s called the Risorgimento, which featured anti-Catholic views. Growing up in Italy, however, ensured that he had been immersed in Catholic culture prior to adopting anti-Catholic sentiments. In Dana Gioia’s The Catholic Writer Today, he distinguishes between degrees of literary Catholicism. Based on Gioia’s distinction, Collodi seems to be a writer at least close to being a “cultural Catholic” who “gradually drifted away” and whose “worldview remains essentially Catholic, though their religious beliefs, if they still have any, are often unorthodox.”[4] According to Gioia,

The Catholic worldview does not require a sacred subject to express its sense of divine immanence. The greatest misunderstanding of Catholic literature is to classify it solely by its subject matter. Such literalism is not only reductive; it also ignores precisely those spiritual elements that give the best writing its special value. The religious insights usually emerge naturally out of depictions of worldly existence rather than appear to have been imposed intellectually upon the work.[5]

Collodi’s voice, Nembrini argues, reveals the Catholic worldview that was merely hidden and which had never disappeared from the Italian consciousness. Nembrini’s Christian insights, then, naturally follow from his deep appreciation and understanding of Pinocchio.

Deeper Into Christian Mystery

The unconventional structure of this book raises questions regarding the reader’s approach to the book. So how do Nembrini’s reflections impact our reading: Are they more like a scholarly gloss of the text, or do they invite a more devotional-like reading practice? Should our reading of fiction be more like a spiritual discipline or an intellectual pursuit? His reflections are careful in showing us “those spiritual elements” and “the religious insights” that make us more sensitive to the story’s poetic vision, leaving the reader with plenty of space for her own analysis and reflections.

Reading Pinocchio with Nembrini feels like reading along with a friend who has reflected on this timeless tale for years. The more I learned, the more I wanted the story to take me deeper into Christian mystery, delighting in the wonder Nembrini sparks. His reflections enlarge the mystery of human life, teaching us not just how to read but to read our experience between the lines of the story.

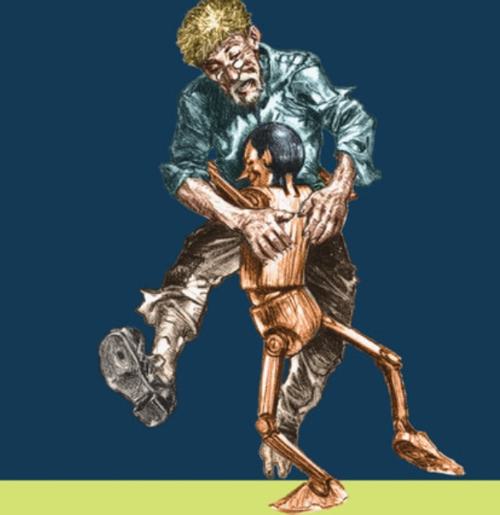

The cover art gestures to the joy of the prodigal son returning home—the perfect entry point to a book imbued with Divine Love. Nembrini’s reflections become a mirror that reveals our own identity as made in the image and likeness of God and our freedom to choose a life untethered from our puppet strings and pride. Once we see this, we realize that the loves that shape our lives and make us really real are gratuitous gifts of God the Father. But this theological reality is something only a true guide, a real critic, can help us see.

[1] Gene Edward Veith Jr., “Reading and Writing Worldviews,” in The Christian Imagination: The Practice of Faith in Literature and Writing, ed. Leland Ryken (New York: Waterbrook Press, 2002), 118.

[2] Ibid., 41.

[3] Ibid., 42.

[4] Dana Gioia, “The Catholic Writer Today,” in The Catholic Writer Today and Other Essays (Belmont, NC: Wiseblood Books in association with TAN Books, 2019), 21.

[5] Ibid., 20.