Monster. Directed by Masayuki Kojima. Based on series by Naoki Urasawa. Aired on Nippon TV, April 2004–September 2005.

It is commonly recognized that persons find themselves only in community, insofar as our identities, whilst our own, are always conditioned by the communities we belong to. However, what happens to our identity when community is torn away from us? I would argue that if being part of a community makes us human, then being sundered from community results in our becoming “monsters” in two senses: the monster that is a portent of terror, and the monstrosity that arises from being unmoored from history, community, and identity.

Typically, when we think of monstrosity, we think of physical deformity, beings that are so hideous in appearance that they cause us to turn away in fear. But there is a subtler type of hideousness, not related to physical form, but to time. To understand this temporal dimension of monstrosity, we need to attend to the etymological dimension of the word “monster.”

In Latin, the root word for the noun “monstrum” is the verb “monere,” which means “to warn.” In this definition, the locus of monstrosity is not in the physical present, but in a temporal future, such that what magnifies the terror of the monster is the person’s being left alone with no sense of the dangers that lie lurking before them beyond those concocted by their unguarded imagination. Indeed, it is precisely the lack of any tangible connection to the present and to others that is the source of the monstrosity. The monster is that anonymous and threatening future that hurtles itself towards the lonely, isolated individual who has no one to rely upon for support or to verify that the threat even exists.

What a temporal appreciation for the word “monster” helps us to understand is that there exists a crucial nexus between time, identity, community, and monstrosity: that the sense of who we are in the temporal present is vulnerable to the shapelessness of an unknown future and to a loneliness before what might be coming towards us. Yet, such vulnerability arises only when left alone and completely marooned. Under such conditions, the specter of our imagined monsters will have an even more corrosive effect on our identity. Put more positively, the stability of our identities is found in their being anchored in a community, whose intercession in the present dispels the specter of the future monsters projected by our imaginations.

In a culture where loneliness is now the norm rather than the anomaly, stable communities that provide stability to our identities are now in increasingly short supply. With our increased atomization and constant flux, perpetual renewal has now become the new cultural imperative and, consequently, the possibility of our becoming monsters multiplies.

Naoki Urasawa's 74-episode anime series Monster (directed by Masayuki Kojima) provides a slow, graphic, confronting, blow-by-blow account of a person’s relationship with past, future, and others. In keeping with the title, the series provides a visceral portrayal of both the personification of monsters, and of how close a person—even one we consider “good”—can be to becoming a monster themselves.

The series begins with a cascade of texts, an introduction familiar to many anime fans. But what a viewer might not expect is that this introduction is comprised of excerpts from the Book of Revelation, passages that evoke the most explicit of biblical monsters: the beasts of the Apocalypse. The series of texts ends with “and they also worshipped the beast and asked ‘Who is like the beast? Who can fight against it?’” (Rev 13:4). At a surface level, what makes the monster monstrous in this passage is its undefeatability and its pretension to uniqueness, its being incapable of imitation. In being so utterly set apart from others, the beast is also set apart from any community of belonging. Even as it stands amidst a sea of devotees, it nonetheless stands alone, inspiring fear as well as awe. In other words, built into the emphasis of the beast’s uniqueness and indomitability is the idea that to be perpetually unique, one must remain perpetually aloof, lest the beast be set among equals who could then, in turn, overcome it. This is the fundamental claim of Urasawa’s series, that loneliness and being in a state of constant withdrawal into oneself is the raw material for becoming a monster.

The series begins by introducing us to Kenzo Tenma, a brilliant Japanese brain surgeon working in Düsseldorf. He is engaged to Eva Heinemann, the daughter of a powerful hospital director who becomes an important, recurring figure in Tenma’s life. One day, Tenma defies Eva’s father by working to save the life of a boy named Johan who has ostensibly been shot in the head by his twin sister. While Tenma’s efforts to save Johan’s life are ultimately successful, he does not know what his saving labor will unleash.

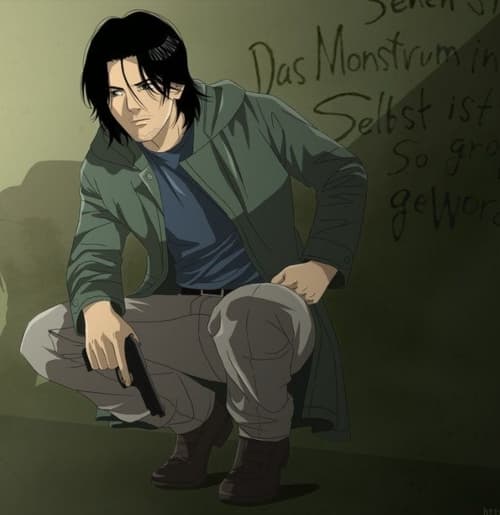

Many years later, a series of brutal murders takes place around Düsseldorf. When the lone survivor of one of these attacks awakes from a coma, he repeats one sentence over and over, warning all those around him: “The monster is coming!” Later, it is discovered that the monster is Johan, who, in apparently thanking Tenma, now frames him for the murders. Johan does this with apparent foreknowledge of what would become of Tenma, with his gratitude stemming from a desire to turn Tenma into a mirror image of himself. For, like Johan, Tenma now comes to live the life of a fugitive, with his community of friends and his family gradually becoming excised from his life. It is Tenma’s quest to clear his name and seek Johan out—to fight the beast and kill him—that drives the series forward.

Tenma comes to understand the source of Johan’s monstrosity. Following his saving the boy’s life, Tenma discovers that Johan was housed at an orphanage that performed human experiments on its residents, 511 Kinderheim. The experiments solidify who Johan is in embryonic form, an orphan stricken from family and left alone. Johan’s status as an orphan and loner follows him into adulthood, as he lives out the consequences of one deprived of a biography and a community, a person without loyalty or stability, assuming numerous different identities as the series unfolds.

Johan also uses those around him like disposable instruments, betraying his associates and cutting them loose after every round of killing. Johan even sees himself as being disposable, embracing the prospect of his own death, both of his past identities and even his own person, whenever it suits his purposes. He uses his lack of any biographical records to evade detection, leaving behind one made-up profile after another, as he moves from one town to the next, killing again and again. Johan is a monster, not only because he is a killer, but because he is a shapeshifter. He rides on a flux of one disposable identity—and at one point even an assumed gender—after another, in which is seen his desire to escape the confines and vulnerabilities that come with commitment to human community.

What is striking about Johan the monster is that he is a gruesome parody of another Johan: John the beloved disciple of Jesus, the author of the passages from Revelation referenced at the beginning of the series. On the surface, Johan and the biblical John both appear to be somewhat abstract figures, with the latter referred to in the Gospel simply as “the disciple Jesus loved.” This abstraction is also apparent in his authorship of Revelation, with John’s own personal contributions being difficult to discern with respect to the contents of his rapturous vision. The difference lies in how that abstraction is treated by each. Unlike the monstrous Johan, who uses his abstraction to evade those he might encounter, the biblical Johan uses his abstraction to paradoxically become more concrete to his readers. In some well-trodden biblical traditions, John’s abstractness allows him to act as the stand-in for every member of the faithful. What sets the biblical John apart from the monster Johan is that while Johan uses his abstractness in order to shield himself from the vulnerability borne by committing himself to those that behold him, the disciple John allows himself to serve as a stand-in for the reader, drawing the one beholding him into an abiding belonging, a communion of disciples with Jesus Christ. In keeping with the biblical passages at the beginning of the series, the monster Johan is an anti-John who tries to outdo the biblical John by promoting himself from disciple to master, gathering acolytes of his own to adore and serve him. Ironically, the monster Johan is almost ontologically allergic to any communion whatsoever, the result being that his disciples are cast aside as easily as they are picked up.

We can see from the above that Johan is defined by his sundering from any community, and it is this that results in his becoming monstrous. By contrast, Tenma also risks becoming monstrous in becoming caught up in the web of intrigue cast by Johan, but in his case this is due to his being stricken from his communion with the future. Johan’s framing Tenma for murder ruins the latter’s future, which is no more vividly presented than in Tenma’s separation from, and later persecution by, his fiancée Eva who, heartbroken to the point of madness, seeks revenge by constantly pursuing Tenma throughout the series. Her ongoing presence in the series serves as a painful reminder to the viewer of what Tenma’s identity could have been—a future loving husband—but can no longer be. Eva’s presence acts as a living void in Tenma’s identity, which parallels the similar void of identity in Johan.

Another parallel between Tenma and Johan lies in the way Tenma begins mimicking Johan over the course of his pursuit. Like Johan, Tenma becomes a vagabond, wandering from town to town, and country to country, assuming different identities in order to avoid detection by the police. But what distinguishes Tenma from Johan is that along the way, the tender shoots of community spring up to fill Tenma’s social void. Despite this, Tenma still tries to sever ties to the people and places around him, taking pains (both figuratively and literally) to drive his companions away as a way of protecting them from Johan. More chillingly, in order to properly prepare himself for the final showdown with Johan, Tenma also undergoes his own transformation, improving his skills of evasion, while also gaining mastery in military techniques. These augmentations mask another tendency in Tenma, a willingness to kill without remorse. Over the course of the series, the viewer watches as Tenma gradually comes to resemble Johan more and more. In fighting the monster, Tenma almost becomes the monster. But what ultimately saves Tenma is precisely the thing that Johan either refuses or was refused, true communal ties that weave in and out of Tenma’s life to shield him against the specter of his ruined future. These ties emerge precisely because Tenma, unlike Johan, refuses to turn those around him into instruments for his own use and enjoyment. Indeed, at regular intervals he goes out of his way to protect them, even at the risk of his own life. This movement out of himself is what leads those that orbit around him to stubbornly hold onto him throughout, despite his efforts to keep them away for the sake of their safety. A community of belonging that abides throughout Tenma’s ordeal is what anchors Tenma’s identity and ultimately, his humanity.

Viewers of Urasawa’s Monster might feel comforted by the thought that they are nothing like Johan, thinking that because they have never killed, they are safe from the threat of resembling the monster. Yet the mutual opposition between Tenma and Johan hides an unsettling similarity, suggesting as it does that anyone can become a monster when cut off from their sense of belonging to people and time. In a culture where loneliness is now the norm rather than the anomaly, stable communities that provide stability to our identities are now in increasingly short supply. With our increased atomization and constant flux, perpetual renewal has now become the new cultural imperative and, consequently, the possibility of our becoming monsters multiplies. Urasawa warns us of what awaits those who strive to be alone, but also shows us how bonds with others continue to serve as points of resistance against the beast.

Matthew John Paul Tan is Dean of Studies at Vianney College, the seminary of the diocese of Wagga Wagga in Australia. He also serves as Adjunct Senior Lecturer in Theology at the University of Notre Dame Australia. He is the author of two books, his most recent being Redeeming Flesh: The Way of the Cross with Zombie Jesus (Cascade 2016). He also blogs at Awkward Asian Theologian, which seeks to bring academic theology and personal experience together.