Jeanine Tesori, Grounded. Libretto by George Brant. Premiered October 28, 2023.

The true hero, the true subject matter, the center of the Iliad is force. The force that men wield, the force that subdues men, in the face of which human flesh shrinks back. The human soul seems ever conditioned by its ties with force, swept away, blinded by the force it believes it can control, bowed under the constraint of the force it submits to.

– Simone Weil[1]

Although said of the Iliad, this pronouncement by the French philosopher Simone Weil could just as well be applied to the new opera Grounded and its main character, Jess, a fighter pilot in the Iraqi war who is reassigned to Las Vegas as a drone pilot (i.e., “grounded”) after becoming pregnant. Commissioned for the opening of the 2024–25 Metropolitan Opera season, Grounded is an adaptation of George Brant’s widely acclaimed play of the same name. Created and composed by Jeanine Tesori, the opera was originally performed at the Washington National Opera in 2023 with Jess played by mezzo-soprano Emily D’Angelo and tenor Ben Bliss as Jess’s husband Eric.[2]

Following the pattern set by Weil, Grounded begins with Jess thinking herself the master of the force she wields in war, realizing only later that it is she herself that is the one conditioned by these powers. Jess is swept away, blinded by forces that manifest in dissociative experiences, family trauma, and dysfunction. She is subdued, reduced to a mere thing, by the same force she wields, only to then later break out of this cycle of violence when she—as Weil herself notes in her essay—recognizes in solidarity the human dignity of another.

Grounded’s opening aria “Into the Blue” was seemingly written with Weil’s epigraph in mind:

Blue

The Blue

I am the Blue.

I am alone in the vastness, and I am the Blue.

High on the sky,

On the solitude,

The freedom,

The peace

Blue saturates me,

Fills ev’ry cell.

The Blue is my reward,

I earned it.

I earned it through sweat and brains and guts.

It is mine.

All of it.

My suit: My second skin

My passport to the sky

My ride: My Tiger

My gal who cradles me, who lifts me up

Into the Blue

The Blue

This aria vividly illustrates Weil’s concept of force and its consequences. Jess’s F-16 fighter jet, her “Tiger,” embodies the force that both empowers and enslaves her. It “cradles” and “lifts her up,” echoing Weil’s description of a force that sweeps away and blinds its wielder. The pilot’s suit, a “second skin,” represents the physical transformation force imposes, a “shrinking” of flesh as Weil describes it. Believing she controls and authors this power, Jess becomes subdued by it, swept away by the vastness of the Blue, and mirroring Weil’s observation of how often we are deformed by the very forces we claim to command. The pilot’s sense of earning her reward through “sweat and brains and guts” reflects the intoxicating nature of power conceived as force, blinding her to its true impact. Only at the journey’s end will she discover true freedom, aligning with Weil’s insight that no one truly masters power; it inevitably transforms both its wielder and its victim.

This power is abruptly taken from Jess when she becomes pregnant as the result of a one-night stand while back in the United States. Her first option—that of abortion, offered by her commanding officer—is rejected and as a result Jess is grounded. This is her first recognition of another’s dignity and her consequent breaking out of the cycle of violence by an act of compassion. Electing instead to remain grounded, Jess returns to live with Eric, the child’s father, and spends several years seemingly happy in their life together. Jess then applies to return to her “Tiger” but finds herself instead assigned as a drone operator near Las Vegas. This relocation is sold to her as an opportunity, allowing her to remain home with her family rather than being deployed overseas, with much of the opera’s drama being how this experience plays out.

Power “petrifies the souls of those who undergo it and those who ply it.”

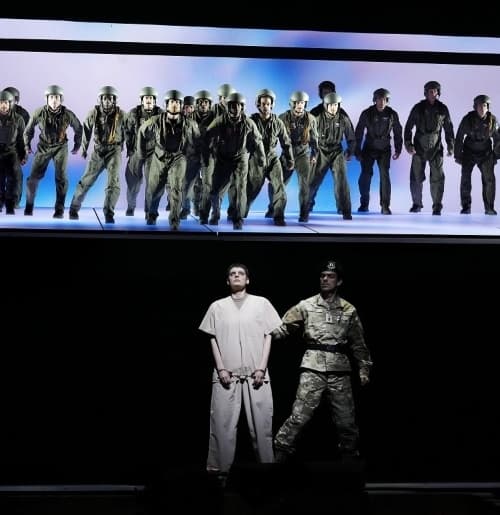

The strength and power of opera as an artistic medium comes to the fore as Jess’s spiral into mental crisis plays out before our eyes. Much has been written about the dissociation experienced by drone pilots who find themselves carrying out brutal bombings by day and then returning home to family and friends at night. This disassociation is further compounded by the inability to share any details of one’s daily experience, restrained by the axiom “It’s classified.” This occasions in the opera the introduction of an alter-ego character, “Also-Jess,” who represents Jess’s dissociation and inability to separate her professional life as a drone pilot from her personal life as wife and mother. Also-Jess sings from the lower stage where she cares for her home and family, while Jess sings from the upper stage where she flies her Reaper drone, with this distinction itself representing the dissociation and divide under which she labors. The power of the military complex is here presented above and over the weakness of the family, with the music itself reflecting this dissonance as Jess and Also-Jess sing as though in competition with one another. The lighting is also often intense and blinding, with LED panels that serve as floor and backdrop of the upper stage, and which add to the confusion and disconnect from reality as they pulse and switch on and off in varied orders and rhythms. The “kill chain” is a particularly effective and other-worldly technique, comprised of the mission coordinator, ground control, joint terminal attack coordinator, safety observer, and judge advocate general, they reflect a chorus of off-stage voices each individually singing commands into Jess’s ear.

All these dissociating and conflicting elements rob Jess of her ability to live and function normally. They combine to hold a power over her which she is seemingly powerless to deal with, having not only been downplayed by the military but hidden beneath the façade of “going home every night.” Indeed, as Jess sings “it would be a different book, The Odyssey, if Odysseus came home every day,” the listener has trouble imagining how it is that she might pull herself out of this spiraling tension between violence and domestic life.[3]

As Jess swirls deeper into this labyrinth, a key high-value target is identified, The Serpent. He eludes the constant drone surveillance by staying in his car, thus not allowing a positive identification for the kill to be carried out. He slips up one day when Jess is flying the Reaper. His daughter is outside waiting for him so he gets out of the car to rush her to safety. This is Jess’s second recognition of another’s dignity. Refusing the kill order, she chooses instead to destroy her own Reaper, while another team carries out the mission, killing the Serpent’s daughter along with him at the same time. As a result, Jess is court-martialed for insubordination and imprisoned.

Implicit in the opening sentence of Weil’s essay is the idea that power “petrifies the souls of those who undergo it and those who ply it.”[4] Jess herself acknowledges “I nearly lost my soul,” while it was only by destroying her drone out of love for her daughter—a dignity she recognizes in the Serpent’s daughter—that the heart petrified by power is removed and replaced by a heart of flesh.[5] And so, even in the midst of her imprisonment, Jess can sing from her cell “I’m free.”

A final word from Weil perhaps aptly summarizes the lesson learned by Jess: “It is impossible to love and to be just unless one understands the realm of force and knows enough not to respect it.”[6]

[1] Simone Weil, Simone Weil’s The Iliad or the Poem of Force: A Critical Edition, ed. and trans. James P. Holoka (Peter Lang, 20087), 45.

[2] The author attended the opera at the Metropolitan Opera, Lincoln Center, NYC October 2, 2024 as well as the MetHD encore broadcast October 23, 2024.

[3] A unique power of the medium of opera itself is the ability to combine so many different artistic elements that converge in different forms—music, lyrics, voice, lighting, stage design, off-stage action, characterization—and effectively portray a phenomenon—in this case psychological splitting/dissociation—that one would otherwise have difficulty experiencing and/or imagining. I am reminded of the opera Fire Shut Up in My Bones in which a dream sequence portrays the experiential reality of having been sexually abused as a child.

[4] Weil, 61.

[5] “I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh” (Ez 36:26, NIV).

[6] Weil, 67.

Gerard Brungardt is a professor of Internal Medicine at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita.