It’s a question bouncing around Steubenville, Ohio, a Rust Belt city that has become home to a new venture in Catholic education: The College of St. Joseph the Worker, a school designed to graduate students with no debt, a job in HVAC, electric, carpentry, masonry, or plumbing, and a BA in Catholic Studies. It’s a venture that seems to require some justification.

There is much that could be said and is said, by unions and technical colleges nation-round, about the trades: they resist automation; they deal with essential needs that fashions won’t sway; they’re more fun than office work; they’ll put you to work and free you from debt far faster than the usual post-college shuffle. All of this is true, but it is also true that God became a tradesman. Jesus, while he walked on the earth, honored a good number of occupations, likening his mighty work to their humble trades: he was called sower, gardener, shepherd, servant, and king. The early church called him everything from banker to builder. But he really was “the carpenter’s son,” skilled with a hand plane and heir to a useful profession.

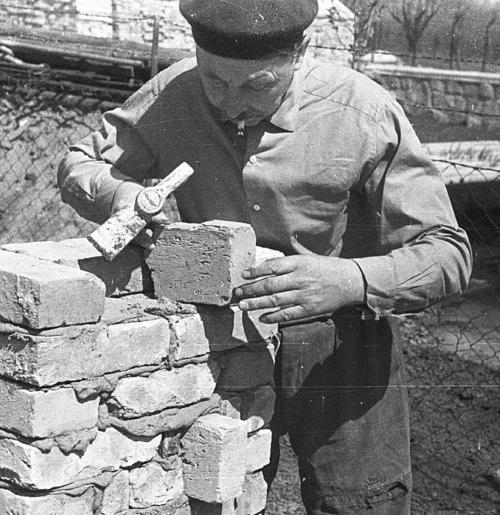

This same Jesus told his followers, more than anything else in the Gospels, to “be not afraid.” Anyone who has met a carpenter or a car mechanic (or any tradesman, really) knows that this heavenly message is not unrelated to our Lord’s earthly vocation, but flows from it. For it is the chief glory of the tradesman that he is not afraid; that he has developed some mastery over some otherwise daunting material; that he wields some particular skill which enables him to hope where others despair; that he can take up the world into his own dominion and shape it, fix it, break it, and mend it. The tradesman has freedom in relation to the built world, a freedom he first received from someone who stood in persona Iosephi to him, guiding his wobbly hand and speaking into his ear: “Someone built this, and so you can too. Don’t be afraid of the saw, but respect it. Follow the grain.”

The tradesman’s direct communion with the inner workings of the built world produces a skepticism of mechanical systems presented as inevitable, necessary, or even natural, that is, as going on apart from human freedom and responsibility.

The thing is best known by a contrast: we fear, and we do so quite a bit. Most people survive the misery of life by the careful activation of systems, from phones to cars to office workplaces and government outposts. Most people do not know these life-support systems from within, cannot take them up and consider them as the young Jesus considered the table, the chair, and the cross: with the knowledge of how it hangs together, of the intelligence that arranges the thing, of its weakness and strength and, most importantly, its contingency as an artifact, the fact that it might have been put together differently, or not at all. Rather, we wake, caffeinate ourselves, stumble out the door to make the money necessary for the whole business, get into the 2009 Honda Accord, and—nothing. A gurgle. A half-attempted turnover. No recourse, no mastery, no dominion, just the revelation of the servile self to itself.

The man stuck in his own driveway suddenly knows himself, not as a cause of things, but as given over to things. If he lingers too long in the driveway, he might get to thinking of his furnace (which room is it in again?), his boiler, his credit card, and the grocery system. He may get to thinking of the way in which his warmth, his shelter, and his very means of survival are only available as commodities, purchased from elsewhere, at the command of cash or credit. This alienation from the means of his own survival is a condition traditionally referred to as slavery; we may all at least admit that such a condition is scary.

Now it is the principle aim of our technocratic behemoth to maximize fear to the utmost (for reasons sundry, and all of ‘em bad), and almost every technological innovation of the past fifty years can be equally described as an invitation for man to give up some skill whereby he owns his own means of survival, his means of getting along, in exchange for a commodity whereby he pays some company or other to “get along” for him. Thus, we travel by instructions rented from Alphabet and Apple; thus, cars and tractors are built to be unfixable by anyone but a licensed dealer; thus, even the most basic forms of communication are mediated and made by possible by devices over which we have only a modicum of mastery; and everywhere a fog of fear surrounds even the most commonplace household objects: Isn’t it considered virtually criminal to do your own electric work? Don’t we shudder to imagine the plumbing job as being something we are responsible for? Shouldn’t we, after all, have some sort of certificate to open up the furnace?

Not being afraid is the prerequisite for any fruitful encounter with reality, and the first and final lesson of every trade. The trades allow you to enter into the sort of communion with the world whereby you perfect it, and it perfects you. This encounter with the world as genuinely belonging to my skill—even when my skill is specialized to stone or wood—spreads out into the whole of my life, affords me a recognizable, existential stance. Done right, having

a skill is subordinated to the being of the one who has it: becoming capable of certain work is a means and a mode of becoming someone. Who, precisely, does the tradesman become?

Typically, the tradesman becomes someone with a “can-do” attitude, a cliche of American politics, but one worth saving: for the one who can do is one who can give. (And what he gives is survival, warmth, and shelter, where so many jobs can only give luxuries.) He becomes someone who knows artifice from within and, therefore, someone habituated to see through artifice, all the way down to the resplendent fact that “someone did this.” This knowledge produces freedom: it allows the tradesman to say, not just theoretically, but with his life: “then I can do it too.” Unlike the operation of interfaces that makes up most work today, the tradesman’s direct communion with the inner workings of the built world produces a skepticism of mechanical systems presented as inevitable, necessary, or even natural, that is, as going on apart from human freedom and responsibility. The Gospels record Jesus as a man in a dogged fight with lawyers, scribes, money-changers, and the like, and the mystery of the battle can cloud the mundane fact—that this is ideal tradesman behavior; that Joseph’s words are on his lips; that, whenever we see a contractor enraged at the obfuscations of white-collar bureaucrats hungrily guarding the gap between his skill and the others’ need, there—sans all the cursing—we see Christ.

Where the rich man can only walk away sad, because he is determined by his many possessions, Jesus sees through them, down into the freedom of the human heart which can cling or not cling to wealth. Where the Sabbath law is described as a fatalistic mechanism, Jesus makes it a gift of life: “the Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). This insight applies directly to all legal regimes and all technologies, all the way down to the 2009 Honda Accord: for “the car was made for man, not man for the car,” and so too the phone, the furnace, the building code—even money. It is an insight especially available to the tradesman who knows, most intimately, that all this artifice is for man; that wherever it enslaves him (wherever we end up serving the car or the money, and not the other way around), justice demands our liberation. For these things are given over to human reason, however alienated we may feel from the fact. “Someone built this,” from the American Constitution to the bathroom sink. It is easy for academics and corporate hustlers to throw up their hands, to equate technocratic slavery with some natural disease, to say of our inability to move and thrive in a world of devices—“that’s just the way the world works.” But the conscience of the tradesman rebels. He knows better. He knows artifice from its very beginning, knows the freedom and decision that brings it into being, knows that it all might not have been, and that it all might have been otherwise, and so bears the responsibility of reminding a world of coders, traders, lawyers, and those under them, so prone to mechanistic presumptions, that we really are responsible for our world.

Obviously, I speak in the ideal. The trades can be corrupted as anything else, can become afraid, especially through the vice of greed, which would make money into the true purpose of the skilled trades, and so open them up to the same illusion of necessity and mechanism as white-collar work: giving them over to “the market,” tending them towards automation, smothering them with intolerable blankets of bureaucracy, and infecting them through with plain, old-fashioned dishonesty. A school that desires Catholics to become tradesmen is only coherent if it desires, at the same time, that the trades become Catholic. America needs the independent and honest tradesman as a spiritual father and a light to the nation, one that reveals the living, beating heart of freedom that is the source of our increasingly impenetrable machinery. But the tradesman, for his part, needs Christ, the master carpenter, to carve him into shape; needs Christ, the mason, to chisel him into a living stone. If God wills it, this meeting of the Church and the trades will provide our Republic with a generation of workers who can fix, not just our teetering infrastructure, but our spiritual malaise; who can replace, not just our built-to-crash housing, but our alienation from the means of our survival; who can build, not just our cities, but the City of God.

Mark Barnes is editor of New Polity.

Posted April 12, 2023.