"Even for monks playfulness may become a moral virtue." —The Right Rev. Dom Paul Delatte, Third Abbot of Solesmes

For the monk that I am—belonging to the older Benedictine tradition of a strictly contemplative form of monastic life—the question of recreation is directly related to the topic of silence, which is one of the fundamental elements of monastic spirituality as dealt with in Chapter Six of the Holy Rule of Saint Benedict. Since the monk is tending with all his soul to a deeper prayer and union with God, he must practice a true silence, so as not be led away from God by the distractions of daily life, many of which come through the sense of hearing. But how complete should this silence be? It would seem that exceptions must exist to the rule of silence.

Indeed, a monk must practice silence, but he must also maintain a human balance. Saint Hildegard of Bingen, Doctor of the Church, sometimes styled the “Sybil of the Rhine,” states categorically that “it is inhuman to keep perpetual silence and never to speak.”[1] Even for monks the Greek virtue of ευτραπελία (a pleasant wit) can become a truly moral virtue. Saint Thomas Aquinas agrees with Aristotle and Saint Augustine in finding it useful for the good of the soul.[2]

Historically speaking absolute silence for monks or nuns has been very exceptional, even in the East. The monks of old probably spoke less than we do in the twenty-first century, but they did speak with one another outside the times of prayer. The Rule of Saint Basil allows the breaking of silence with moderation and for good reasons.[3] The Rule of Saint Pachomius mentions a conversation each morning.[4] The Rule of Saint Benedict, which Benedictines still follow today with certain modifications, does not mention recreation (a modern conception), but there exist something like it among the monks of the Order. At the great Benedictine abbey of Cluny, in the Middle Ages, there were two set times daily (except for Sundays and certain other days) when the brethren were allowed to talk in the cloister. The morning conversation did not go much beyond a half an hour, and in the afternoon this period of recreational conversation lasted sometimes less than a quarter of an hour. Even the very austere Saint Bernard permitted his conferences given to the brethren in the chapter room to take on a recreational character, stopping from time to time to exchange lighthearted words with some of his monks, as a close study of the history of his life reveals.[5]

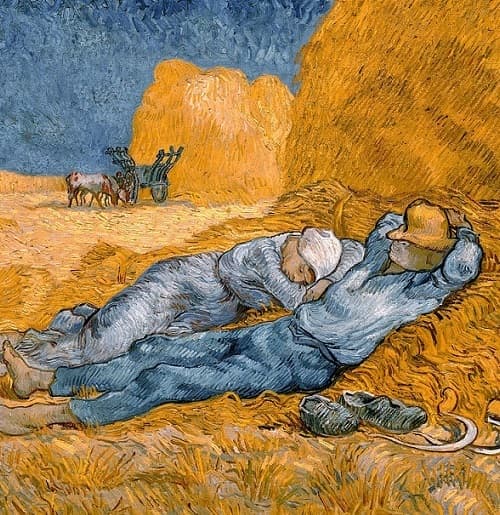

Practically speaking, in our monastery, we have a period of recreation immediately following the midday meal and the dishes. Most days this period lasts a little over one half an hour. The monks first meet together in the cloister to hear a few news items from the Superior; then we go for a walk through the monastery grounds in groups of three to five, engaging in lively conversation. On Sundays the period is a full hour. Once a week we have an even longer walk, lasting up to three hours. This allows young men to burn off energy as they walk for ten miles or more through the countryside (often outside the monastery property). Sometimes, in the middle of the summer, the monks swim in Clear Creek, which is truly clear and very cool. On such a walk in the wilder places we may encounter a wild boar or a water moccasin—keep your eyes open!

Now here is a somewhat controversial point, one that was dealt with a great length (though rather poorly I would say) in the historical mystery novel by Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose. We might pinpoint the controversial matter with a question. Might there be mirth and laughter during a monastic recreation? At first sight this would seem out of the question for monks professing vows under Saint Benedict’s Rule. Here is the pertinent passage:

But as for buffoonery or silly words, such as move to laughter, we utterly condemn them in every place, nor do we allow the disciple to open his mouth in such discourse.[6]

One could hardly be clearer: aeterna clausura [in every place].Had we no other indications to go by the question would be settled. However, here as in many aspects of monastic life, we must read the Rule in the context of the living tradition, taking into consideration the way this warning from Saint Benedict has been understood over many centuries by monks and nuns.

In fact, Saint Benedict does not mean to forbid a sense of humor and of gaiety in these moments of monastic recreation. Abbot Paul Delatte of the Solesmes Abbey in France explains this very well in his Commentary on the Rule.

There is wisdom in avoiding the prudery which is shocked and scandalized by everything; when we are good, the peace and innocence of childhood, its moral naïveté, return to us. Still it remains true that there are certain subjects, a certain coarseness, a certain worldly tone, which should never enter our conversation. These things are not such as to stir wholesome laughter; there are matters which one should not touch, which it is wholesome to avoid. Our own delicacy of feeling and the thought of Our Lord will save us from all imprudence.[7]

To this might be added another text of Saint Benedict, where he bids his monks “[N]ot to love much or excessive laughter.”[8] If the monk is directly to avoid excessive laughter, there must have been allowance for its moderate use.

Perhaps, in summarizing the matter of laughter and pointing to the essence of monastic recreation, we might say that the genuine joyfulness of the monk on recreation expresses itself in the smile rather than in outright laughter—especially of the violent or uncontrolled sort. Joy is a spiritual quality that is essential to monastic life, and it is only natural—supernaturally natural—that this joy find a form of facial expression. Such joy does not disturb religious silence. When the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared to the children of Fatima or to Saint Bernadette of Lourdes, she smiled in a way that moved the soul of the seer to its depths. How could that not be the very best of recreations?

The Right Rev. Dom Philip Anderson, O.S.B. is the Abbot of Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey in Oklahoma.

[1] Reg. S. Bened. Explanatio. PL CXCVII., 1056.

[2] Summa, IIa IIae, question 168, art. 2.

[3] Reg. Contr., xl., cxxxiv.; Reg brev., ccviii.

[4] Chap. XX.

[5] St. Bernard, Tractatus de duodecim gradibus superbiae, c. xiii. P.L. CLXXXII., 964; Sermo XVI i., de Diversis. P. L. CLXXXIII., 583 sq.

[6] Rule, Cha. 6.

[7] Dom Paul Delatter, The Rule of Saint Benedict, A Commentary (New York: Benzinger Brothers, 1921), 97.

[8] Rule, Chap. 4, Instr. 55.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Liberating Silence in the Dictatorship of Noise.