This year we turn to the Body. There is no question that it is the human body—the “thing” that accompanies us wherever we go—that is behind most of the questions in our collective mind. The body is just there. And now, for that very reason, we are putting it to the test as we reject, starve, exploit, re-build—chemically, surgically, digitally, cybernetically—and finally incinerate it. Though we have been at this for centuries, what has become clearer in recent years is that the dominion of nature at large has at last become the dominion of our nature, especially there where it puts us in relations we have not chosen. We are born of mother and father. As male or female we face the opposite sex (regardless of our “orientations”). And we are being prepared for motherhood and fatherhood (whether that happens or not). This is precisely why we have turned on the body.

Chesterton said that our time would be marked by the denial of everything, that two and two make four and that leaves are green in summer.[1] The same observation has been made by many others, such as Hannah Arendt, who defined the ideology of our day as “the knowledgeable dismissal of the visible.”[2] Both thought that the counter to ideology would be the “defense of this huge impossible universe which stares us in the face” (Chesterton). But what is becoming increasingly clear, is that the “universe” in question is the small one that stares us in the face every morning when get up to brush our teeth. If only we could see what is right in front of our eyes.

The first issue, as with all first issues, takes up the question at its most basic level. What is the human body? What does it say? And what is at stake in all the manner of transformations to which it is being subjected? To begin to answer this question, we cannot help but call upon the master himself, John Paul II, some of whose key texts on the subject grace our ReSource section.

John Paul II knew, of course, that it is not only that we do not happen to hear the language of the body, but that we do not want to hear it. We have silenced the body, not to mention the whole realm of the material universe. And we have done so intentionally, chiefly so that we can try to exempt ourselves from its limitations, (and, failing, obliterate its evidence as Patricia Snow shows in her feature on the new attitudes about burial and cremation in the post-Christian West).

This is what Hervé Juvin means by the “new body” in his Coming of the Body, reviewed here. It is not that the body has changed that much. The body is the body, after all. But our “gaze on the body” has. And in an age where representation means more than nature itself, that is no small thing.

Keeping in mind the fact that having a body is not unique to human beings—that every silencing of the human body is tied to the general silencing of all living bodies—we review The Flexible Giant: Seeing the Elephant Whole by the observational biologist Craig Holdrege, who tries to recover the epiphanic, word-like, character of the living body, whether it be that of an elephant or a sloth (about which he has also written a monograph), or, well. . . of a human. Holdrege is an example of someone who is helping us to open our eyes and ears to that “impossible universe.”

We deal here with also with the tragic and pervasive phenomenon of the “pornification” of the body, especially in its newer digital form. The most recent “bible” on this unfortunate topic—Matt Fradd’s Porn Myth—is reviewed in this issue. Our feature on the transformation of porn under the power of the internet, written by someone whose work is to protect children from it, is sobering. Another feature attempts a “metaphysics” of pornography, suggesting that it is the expression of our long-standing choice for the unreal—the virtual—which we take as more “real” than reality itself.

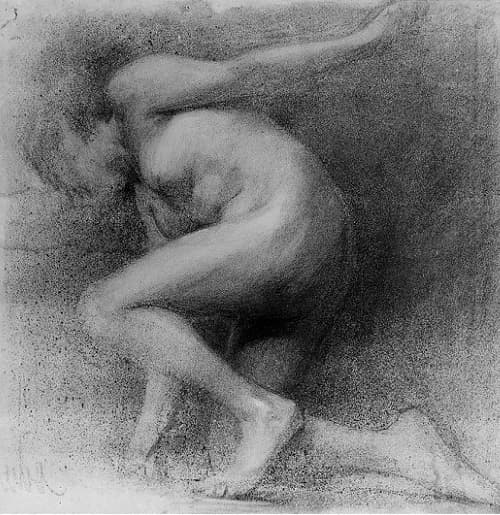

In a way, this is what John Paul II meant when he said that the problem with pornography is not that it shows too much of the body but that it shows too little. It is this diagnosis that has turned many to the importance of art, especially its rendering of the human body. In his early days at the New York Academy of Art,sculptor and painter Dony Mac Manus witnessed the power of John Paul II’s teaching on the body among his fellow students, who packed his discussion room week after week to learn “the one thing they didn’t know about the body”: its meaning. This is why he stresses the importance of the nude. It is an essential ingredient in the “detoxing” of society from its fixation with the non-real, Mac Manus told us in our interview with him. Moreover, says Mac Manus, the nude is capable of doing so because the reality it can re-propose to the world has the capacity to pierce the heart, being in the form of beauty. He is thinking of the “method” of Christianity itself, since there the Truth (Logos) did not remain an object of contemplation and longing, but manifested itself by coming in the flesh then in going to the end,in search of the heart of man.

All of this means, of course, that what counts for what is “beautiful” changes. See our review of A Body for Glory by Elizabeth Lev and Fr. José Granados which delves into the distinct Christian contribution to the artistic depiction of the body as a result of the fact that God Himself made himself vulnerable, giving Himself to man in the flesh. Our feature on the Pre-Raphaelites explores the resilience of that contribution in the cultural ferment of a Victorian age not known for its consistent attitude to the human body, but nonetheless marked by a profound nostalgia for the sacred.

“The capacity of art to pierce the heart—especially by showing the vulnerability of God—is really central to my vision and to the healing of contemporary culture,” says Mac Manus. It is central to ours as well. Happy reading.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the US editor for Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

[1] G.K. Chesterton, Heretics (New York: John Lane Company, 1905), 305.

[2] Alain Finkielkraut, In the Name of Humanity: Reflections on the Twentieth Century, trans. J. Friedlander (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 60.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, John Paul II on the Body in Art and Pornography.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the editor of Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

Posted on June 20, 2018