Suffering and death, though they are unavoidable aspects of life, are often buried under layers of avoidance or dressed up with creative arguments to make their realities palatable. However, death was never meant to be palatable. Much to the contrary, suffering and death are the very things that alert us to the reality of our human condition. They are meant to wake us up, and very seldom are we woken from deep sleep by a feather touch.

Suffering and death, unpalatable as they are, are never meant to close us off to hope. Yet so often public discourse only sees hope in the cessation of suffering or the finality of the death that ends the suffering, as is evidenced by the rise in demand for euthanasia or the preference for “celebrations of life” over funerals. There is an apparent meaninglessness to suffering that is far easier to grasp than the meaning that can be found hidden beneath the immediacy of pain. The greatest challenge of suffering is not to come to terms with the experiences of pain and futility; rather, the challenge of suffering is to seek hope where hope is obscured.

Suffering is what is experienced as the result of a “lack, limitation or distortion of a good”; it is a contact with evil, and evil not something constitutive of itself, but rather a distortion or privation of a good. If we have a physical illness, we suffer because we are lacking health. If we grieve over a relative that has died, we suffer because we lack their presence. There is also something nebulous about describing suffering, in that it is experienced in the double dimension of body and soul that constitute the human person. Physical suffering, that which is tangible and verifiable to some degree, often pales in relation to moral suffering, which is the pain of the soul. However, these divisions are not discrete; most often, suffering of any kind includes moral suffering, even if that suffering is rooted in something physical.

Even in his resurrected body, Christ retains the wounds of his suffering and death; these now become the marks of his victory and proclaim that every suffering, in him, is now linked to resurrection and glory.

I remember the first time I had the thought, “Oh…this is why euthanasia might be appealing.” The topic was already front of mind, because at the time, MAiD was legal in Canada and its availability was being expanded more and more. I had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia some years before, but when my symptoms went from mild to severe, I was left with daily, unremitting pain and debilitating fatigue, among a host of other symptoms. In the face of my own pain, there was no part of me that desired to end my life (thanks be to God), but I distinctly recall having the thought, “I expected suffering to be different than this.”

I had expected suffering to be an experience of intimacy with the Lord—of finding the delights of the cross that I had seen expressed in so many of the writings of the Saints, like St. Teresa of Avila (one of my favorites), who said, “Let us look to the cross and be filled with peace, knowing that Christ has walked this road and walks it now with us and with all our brothers and sisters.” In the presence of the small crosses of daily life, such sentiments came as beautiful encouragements in the walk with Christ along the narrow road. However, enclosed in the tumult of deep suffering, I found these words (and most others) to offer limited comfort in light of the pain I was experiencing. Where I expected to find the compassionate heart of Jesus waiting for me as I joined him at the cross, I found a desert where he seemed hidden…and where I was alone.

This curious phenomenon of being close to the cross, the place of the triumph of mercy and of our salvation, but feeling as though pain overshadows all else, is not just a façade. Though not the fullest reality of the cross, it is a consuming one. Christ himself affirms this in his cry to the Father from the Cross: “Eli, eli, lama sabachthani!” (Matthew 27:46, NIV; cf Psalm 22:1, NIV). St. John Paul II

named the root of this experience: suffering “in dispersion.”

Although there is a consolation that can come through the solidarity formed by those who suffer in similar ways, such as cancer support groups and the like, because the individual person is unique, so too is each experience of suffering unique. The sufferings of one cancer patient and another, even if they both have similar life circumstances, prognoses, treatments, and pain, are necessarily unique simply by the fact that all persons are unique and unrepeatable. Thus, despite commonalities and possible solidarities, suffering itself is inherently an experience of isolation and of loneliness. In fact, the dispersive qualities of suffering can themselves inhibit the solidarity possible among those who suffer. Compounding this reality is the etiology of suffering as the deprivation of a good and a contact with evil. So, then, the one who suffers finds himself to some extent alone, with a longing for a good he realizes is lacking and at least an intuited sense of experiencing the realities of evil.

Even more, the current cultural climate carries an ever-present call to comfort. Even when that comfort is sacrificed for a greater good, such as in one who begins an exercise regime to gain better health, the loss of comfort is tightly controlled by the one who willingly relinquishes it. The issue of control, so tightly bound up with individualism and the belief that we are authors of our own lives (as opposed to co-creators of our lives in cooperation with God), also gives us the illusion of a stability that we build. When comfort and control are lost, as is most often the case with suffering, the answer from secular culture is to gain comfort and control back by any means necessary. The answer from God to the problem of pain is very different: in times of pain, he gives himself.

This is the basis for the staggeringly audacious claim of the Church

that suffering “is something good, before which the Church bows down in reverence with all the depth of her faith in the redemption.” How is one, bowed down under the weight of suffering, to reconcile suffering as a good in light of what their observed reality suggests to them?

The starting point is not one arrived at through mental gymnastics, or even by pushing aside the pain of suffering—it is a question natural to the experience itself. Since “only the suffering human being knows that he is suffering and wonders why,” the question can be reduced to one word: “Why?” The emergence of this question, though it is so often united to fear and discomfort and existential turmoil, is a great good because it opens us to an answer, and to the Giver of the answer.

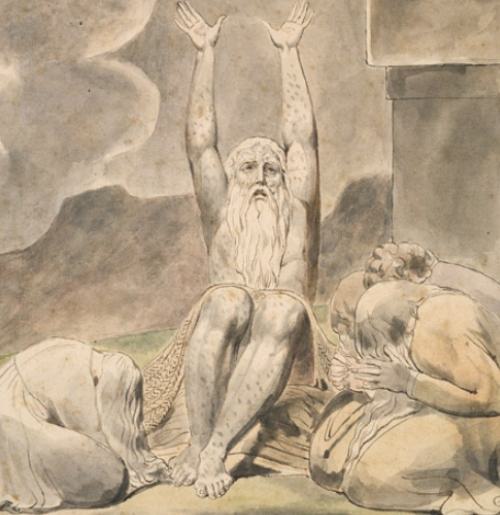

Suffering, in moving from an exercise in futility to one of discovering meaning, necessarily entails entering the storm itself to discover the One who can, in some way, give a word that quiets the internal storm, even if the external storm rages on. It recalls the story of the Israelites in the wilderness, who, following the bites of deadly serpents, need the healing of God (Numbers 21:4–9). God heals the Israelites by instructing them to gaze head-on at the image of what caused their affliction to begin with. St. John of the Cross

writes similarly of this dynamic:

Would that men might come at last to see that it is quite impossible to reach the thicket of the riches and wisdom of God except by first entering the thicket of much suffering, in such a way that the soul finds there its consolation and desire. The soul that longs for divine wisdom chooses first, and in truth, to enter the thicket of the cross… The gate that gives entry into these riches of his wisdom is the cross; because it is a narrow gate, while many seek the joys that can be gained through it, it is given to few to desire to pass through it.

A soul that discovers, in the thicket of suffering, its “consolation and desire” is a soul that recovers hope. Note that John of the Cross doesn’t say that the soul will find an explanation for its particular suffering. Rather, God responds to the question “Why?” by giving himself—the author of all consolation and the ultimate desire of our souls. God works in this manner with Job, whose sufferings were very great, but who receives God’s presence powerfully in the longest dialogue between God and man explicitly recorded in the scriptures. Job never received an explanation from God, but he did receive His presence.

Ultimately, our recovery of hope is found in Christ’s suffering body. In his work of Redemption and descent into the depths of sin and suffering, Christ tied suffering definitively to salvation, and thus the fundamental meaning of suffering is now redemptive. Not only this, but now every human suffering has been incorporated into the totality of suffering experienced and redeemed by Christ and is now linked to love. This is, again, the audacious claim of the Church that suffering can be a good: when borne in love, human suffering participates in the salvific suffering of Christ and can be considered not just a good, but a substantial participation in the supreme good, which is love.

This is the fullest explanation of what is meant when Catholics use the oft-cited and sometimes misunderstood phrase, “Offer it up!” The ability to trust that our sufferings are somehow “filling up what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ” (Col 1:24, NABRE) and participating in his salvific action turns the closed-in posture natural to suffering to an outward-facing offering, where even what is experienced as futility can become efficacious.

Further, it is not only meanings of love and redemption that have been linked to Christ’s salvific suffering, but also meanings of victory and glory. The Church has always understood there to be an inner unity to the Paschal mystery of Christ’s suffering, death, and resurrection, in that no part makes sense apart from the others. Even in his resurrected body, Christ retains the wounds of his suffering and death; these now become the marks of his victory and proclaim that every suffering, in him, is now linked to resurrection and glory. This is also his proposal for us, and a deep source of the recovery of hope: that every cross we bear finds its corresponding resurrection in Christ.

Since we are body-soul composites, our bodies also point towards the truth regarding suffering and hope. The theology of the body describes the meaning of the body as spousal. In short, the body reveals that human persons were created to participate in a communion of reciprocal self-gift, and through such participation, to realize the very meaning signified by their bodies in their masculinity and femininity.[1] As articulated in Gaudium et Spes, “man, who is the only creature on earth which God willed for itself, cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself.” The complementarity of masculinity and femininity that reveals the spousal meaning of the body is not the only form of complementarity that allows the body to live in accord with its spousal meaning. The term used by Angelo Scola to describe the complementarity at the root of the spousal meaning of the body is “asymmetrical reciprocity,” and this form of complementarity applies well to the suffering body.[2]

The spousal meaning of the suffering body directly resolves the perceived meaninglessness of suffering. The fullest expression of the spousal meaning of the body, notably seen in a context of suffering, is seen in the body of Christ on the cross as he gives himself completely for his Bride, the Church.[3] The very presence of one who suffers, and the particular privation causing their suffering, makes possible a communion of persons, an asymmetrical reciprocity, between the sufferer who lacks and the one who responds to that lack, regardless of whether the response directly ameliorates the cause of the suffering. In this way, the suffering person, simply by their presence as one who suffers, invites a response of love from the one who responds and draws that person into the spousal meaning of their own body.[4] Said another way, the suffering person, with no need to do anything, is a gift to others, because someone who responds to the suffering of another is drawn into the very meaning of their own existence. Said in an even more foundational way, suffering is present “in order to unleash love in the human person.”

There is also a final hidden and hopeful truth about suffering with Christ: we possess the ability to grow in our capacity to suffer well and to experience joy, even if there is no diminishment of pain. It seems impossible when the initial weight of our crosses is suffocating, but sufferings which might have crushed us at one point can become lighter over time. This is not because we can grasp more or control more. It is because we become interiorly conformed to the Crucified Christ and touch the depths of the mysteries of love through our pain:

Gradually, as the individual takes up his cross, spiritually uniting himself to the cross of Christ, the salvific meaning of suffering is revealed before him. He does not discover this meaning at his own human level, but at the level of the suffering of Christ. At the same time, however, from this level of Christ the salvific meaning of suffering descends to man’s level and becomes, in a sense, the individual’s personal response. It is then that man finds in his suffering interior peace and even spiritual joy.

In my own experience of suffering, I have come to see more clearly that there is a thicket of the riches and wisdom of God that is open to me. Some peace has come through trusting that Christ has tied my suffering, in his Cross, to love, and that no suffering is wasted when it is borne in union with him. Some peace has come in a very practical way through my own struggle to separate my worth from my productivity. Some peace has come through the understanding that my suffering body can be a place of communion and an instigator of holiness for both others and myself.

The most lasting peace has come as the result of wrestling with God and being honest with myself and him when I feel surrounded by my sufferings and closed in on myself. A very wise priest once reminded me of the story of Jacob, who also wrestled with God, and who would not let God go until God gave him a blessing (Genesis 32:24–28). My own word of blessing has come in a paradoxical assurance from him that he is with me, even when every fiber of my being says he is not with me. Only God could say such a thing and have a human heart believe that it is true.

The importance of the recovery of hope in our sufferings cannot be understated in our current culture. In suffering borne well, the body speaks of the possibility of peace and hope, even in the midst of deep pain. To see just how convincing this word is, we can look to the example of St. John Paul II. Having written profoundly and convincingly, both of the meaning of the body and of suffering, St. John Paul II’s own suffering and death formed what George Weigel fittingly calls a living “last encyclical” written in his very body.[5] Such a witness is not reserved only to the elite few—it is opened as a possibility to every person who suffers with Christ and who, in doing so, brings flesh to the sacrifice of love that saved the world. In truth, it is the credible witness of those who suffer and die in hope that contains the seed of triumph over meaninglessness.

[1] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, trans. Michael Waldstein (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 2006), no. 15.1.

[2] Angelo Cardinal Scola, The Nuptial Mystery (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005), 643.

[3] Peter C. Harman, “Towards a Theology of Suffering: The Contribution of Karol Wojtyla/Pope John Paul II,” (PhD diss., Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., 2010), 374.

[4] Erin Kinsella, “Theology of the Suffering Body: Rereading Salvifici Doloris through the Lens of Theology of the Body” (Master’s thesis, St. Augustine Seminary/University of Toronto, 2021), 57.

[5] George Weigel, The End and the Beginning: Pope John Paul II: The Victory of Freedom, the Last Years, the Legacy (New York: Doubleday, 2010), 514.