Sofia Cavalletti,

The Religious Potential of the Child

(Liturgy Training Publications, 1992).

Sofia Cavalletti,

The Religious Potential of the Child 6 to 12 Years Old: A Description of an Experience

(Liturgy Training Publications, 2002).

This article was featured previously in our inaugural issue on The Child (Fall 2011).

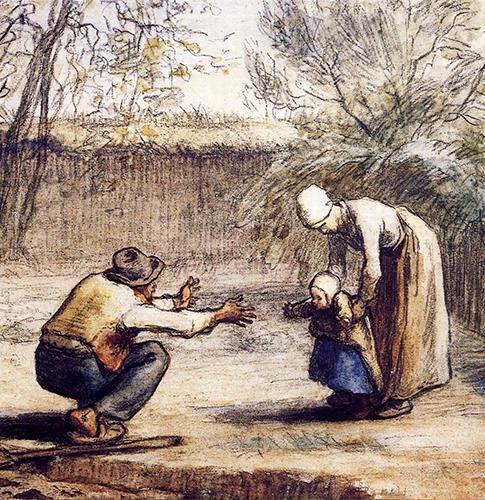

"The religious experience is fundamentally an experience of love... We believe that the child, more than any other, has need of love because the child himself is rich in love." So states Sofia Cavalletti, a noted biblical scholar and educator who lived in Rome and passed away in August 2011 at the age of 94 years. She once reluctantly agreed to a friend's request to give Bible study classes to three children, and was so struck by their interest and joy that she devoted the rest of her life to listening, observing and working with children in order to better understand and nurture the child's relationship with God. Together with Gianna Gobbi, a Montessori educator, she developed the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, a unique and profound religious formation for children aged 3-12 years which is now present in North and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia.

In two beautiful, fascinating, surprising, and sometimes challenging books, The Religious Potential of the Child and The Religious Potential of the Child 6 to 12 Years Old, Cavalletti offers insights from her 45 years' experience of living religious formation with children, and describes the themes and presentations which make up the program of catechesis. However, as Cavalletti herself explains, "the primary intention is not to propose this program but to share what we have glimpsed of the relationship between God and his creatures." In a similar way this review will not explain the practical details of the catechesis, details which are certainly presented in the texts, but rather focus on Cavalletti's profound contribution to the question of the child and of religious formation, a contribution which the Church of today would do well to consider.

Cavalletti begins with the conviction, rooted in her direct experience with children, that there exists a deep relationship between the child and God, a bond which manifests itself even before any religious education or experience of Church, and which may be described as "the certainty of a presence, a presence of love that attracts with a great force... but appears to await a response." She describes the child as "a metaphysical being, who moves with ease in the world of the transcendent and delights in contact with God," and offers many astonishing examples of this in the first chapter of RPOC, "God and the Child."

"In the adult the space of acceptance is never whole, yet it is in the child. The child is really capable of listening impartially and unselfishly, the child is receptive to the greatest degree."

The primacy of this relationship between God and the child governs the whole of the Good Shepherd catechesis. Cavalletti has seen this bond flourish best through a clear proclamation of the essential truth of our faith: God, who reveals his love through his Christ. She does not believe that deep truths need to be simplified or avoided with children, rather she has seen that "the child is satisfied only with the great and essential things." The child is introduced directly into the mystery of the person of Christ through a few essential themes from the Bible and from Liturgy, which Cavalletti determined upon after having seen how the children responded to them with depth and joy (see RPOC chapters 3-8 and RPOC 6-12 years chapters 2-10).

The parable of the Good Shepherd is the central theme for the 3-6 year-old child, revealing the personal love and protective presence of Christ who calls us by name, knows us intimately, and to whom we learn to listen. "Through this parable the child's silent request to be loved and so to be able to love finds response and gratification." For the 6-12 year-old child this image is integrated with that of Jesus as the True Vine (John 15) which introduces the covenant relationship between the Father, Christ, and man, drawing the child into the mystery of a life-giving union with Christ which bears fruit for the world and inviting him to "remain" in this Love.

The depth of wisdom in such an approach to catechesis can be seen in Chapter 9 of RPOC, "Moral formation," where Cavalletti makes the strikingly simple point that if we wait to begin religious formation until the age of moral reasoning, as is widespread in the Church today, then "the meeting with God is confused with moral problems, and God will easily come to assume the aspect of judge." Indeed, we risk this being the primary way in which the person relates to God their entire life. Alternatively, Cavalletti has seen how the child who already knows the protective love of the Good Shepherd is able to navigate the moment of moral crisis in the certainty of being loved despite every incapacity. In this way morality can become an orientation of the whole person, a free response by the child to his encounter with the person of Christ, since "it is only in love, and not in fear, that one may have moral life worthy of the name."

This radically Christo-centric approach governs not only the content of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, but also its method; Cavalletti believes "method has a soul, and this soul should correlate to the content that is being transmitted." Since Biblical religion is that of the transcendent God who reveals himself in creation, throughout history and supremely in Christ, Cavalletti employs "The Method of Signs" (RPOC, Chapter 10). A sign is something which indicates another thing different from itself; "it connect us to the sensible world while it urges us to reach toward the Invisible." It is an instrument in the education of faith, employed by Jesus himself in teaching in parables, kept alive in the Church through the liturgy.

The children are pointed towards the truth that is signified, but left with the work of reaching the reality for themselves. In this way both the truth and the child are respected: "It is a method filled with veneration for the mystery; it does not claim to explain or define. It is a method full of respect for the person and his capacities."

Concretely this means that in the Catechesis the child is presented, through texts and sensorial materials, with the history of the life and death of Jesus, with parables, with the symbols and gestures of the sacraments, and with the richness of salvation history and covenant theology. Cavalletti offers many examples of the fruit such an approach bears in the children; their words and artwork (see the Appendices of both books) reveal a richness of faith, a great deal of joy, and an attitude of humility and wonder in the face of the unfathomable gift which is the Christian message.

It is this deep sense of wonder, naturally present in childhood, which Cavalletti seeks to foster and nourish, for "when wonder becomes the fundamental attitude of our spirit it will confer a religious character to our whole life." In the child, wonder at God's gifts inevitably flows into contemplation and enjoyment of the gifts, into prayer of praise and thanksgiving. The atrium (the name given to the room where the catechesis takes place), is a place of listening to God's Word, the basis of all prayer, and it becomes a holy ground where Christ is encountered in word and action.

Cavalletti's genius is to see, and to make a point of stressing repeatedly throughout her work, that the child and the adult live together this religious experience; the adult might proclaim the Word, but she too must listen. For Cavalletti a catechist is the "unworthy servant" of the Gospel, a mediator between God and the child who must withdraw as soon as contact is made between the Creator and his creature. "The catechist who does not know when to stop or how to keep silent, is one who is not conscious of one's limits and is lacking in faith, because one is not convinced that it is God and his creative Word who are active in the religious event."

I have been privileged to receive training in the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd and assist in an atrium for the last three years, and I can say from personal experience that these insights of Cavalletti are life changing. I have glimpsed how seeking to live in a spirit of poverty as a catechist, as Cavalletti suggests, means accepting that what we transmit does not belong to us and that we cannot claim the fruit. The beauty of making this step is that it leads us to discover afresh the very truth we are transmitting, and it is the children who point the way.

"In the adult the space of acceptance is never whole, yet it is in the child. The child is really capable of listening impartially and unselfishly, the child is receptive to the greatest degree." Living alongside children who are discovering with joy the reality of God's presence, we learn again how to receive the gift of being loved by Love and we might even hope to "change and become like them" (Matthew 18:3).

Ruth Ashfield lives in Surrey, England where she works as a palliative care nurse. She studied Theology at Oxford University before graduating from the Masters program at the John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family in Washington, DC, and returning to the UK to complete her Bachelor of Science Degree in Adult Nursing at Kingston University and St George's Medical School. She is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Biomedical Science at the John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family.