On July 30, 1998, Pope John Paul II promulgated the apostolic letter Dies Domini [The Lord's Day], challenging Catholics to rediscover the true meaning behind the Sabbath Day and, consequently, to "not be afraid to give their time to Christ." This excerpt (pars. 4‒7, 11‒15) was taken from the Vatican website.

Until quite recently, it

was easier in traditionally Christian countries to keep Sunday holy because it

was an almost universal practice and because, even in the organization of civil

society, Sunday rest was considered a fixed part of the work schedule. Today,

however, even in those countries which give legal sanction to the festive

character of Sunday, changes in socioeconomic conditions have often led to

profound modifications of social behaviour and hence of the character of

Sunday. The custom of the “weekend” has become more widespread, a weekly period

of respite, spent perhaps far from home and often involving participation in

cultural, political or sporting activities which are usually held on free days.

This social and cultural phenomenon is by no means without its positive aspects

if, while respecting true values, it can contribute to people’s development and

to the advancement of the life of society as a whole. All of this responds not

only to the need for rest, but also to the need for celebration which is

inherent in our humanity. Unfortunately, when Sunday loses its fundamental

meaning and becomes merely part of a “weekend,” it can happen that people stay

locked within a horizon so limited that they can no longer see “the heavens.”

Hence, though ready to celebrate, they are really incapable of doing so.

The

disciples of Christ, however, are asked to avoid any confusion between the

celebration of Sunday, which should truly be a way of keeping the Lord’s Day

holy, and the “weekend,” understood as a time of simple rest and relaxation.

This will require a genuine spiritual maturity, which will enable Christians to

“be what they are,” in full accordance with the gift of faith, always ready to

give an account of the hope which is in them (cf. 1 Pt 3:15).

In this way, they will be led to a deeper understanding of Sunday, with the

result that, even in difficult situations, they will be able to live it in

complete docility to the Holy Spirit.

From

this perspective, the situation appears somewhat mixed. On the one hand, there

is the example of some young Churches, which show how fervently Sunday can be

celebrated, whether in urban areas or in widely scattered villages. By

contrast, in other parts of the world, because of the sociological pressures

already noted, and perhaps because the motivation of faith is weak, the

percentage of those attending the Sunday liturgy is strikingly low. In the

minds of many of the faithful, not only the sense of the centrality of the

Eucharist but even the sense of the duty to give thanks to the Lord and to pray

to him with others in the community of the Church, seems to be diminishing.

It

is also true that both in mission countries and in countries evangelized long

ago the lack of priests is such that the celebration of the Sunday Eucharist

cannot always be guaranteed in every community.

Given

this array of new situations and the questions which they prompt, it seems more

necessary than ever to recover the deep doctrinal foundations underlying

the Church’s precept, so that the abiding value of Sunday in the Christian life

will be clear to all the faithful. In doing this, we follow in the footsteps of

the age-old tradition of the Church, powerfully restated by the Second Vatican

Council in its teaching that on Sunday “Christian believers should come

together, in order to commemorate the suffering, Resurrection and glory of the

Lord Jesus, by hearing God’s Word and sharing the Eucharist, and to give thanks

to God who has given them new birth to a living hope through the Resurrection

of Jesus Christ from the dead (cf. 1 Pt 1:3).”

[…]

Sunday

is a day which is at the very heart of the Christian life. From the beginning

of my Pontificate, I have not ceased to repeat: “Do not be afraid! Open, open

wide the doors to Christ!” In the same way, today I would strongly urge

everyone to rediscover Sunday: Do not be afraid to give your time to

Christ! Yes, let us open our time to Christ, that he may cast light

upon it and give it direction. He is the One who knows the secret of time and

the secret of eternity, and he gives us “his day” as an ever new gift of his

love. The rediscovery of this day is a grace which we must implore, not only so

that we may live the demands of faith to the full, but also so that we may

respond concretely to the deepest human yearnings. Time given to Christ is

never time lost, but is rather time gained, so that our relationships and

indeed our whole life may become more profoundly human.

[…]

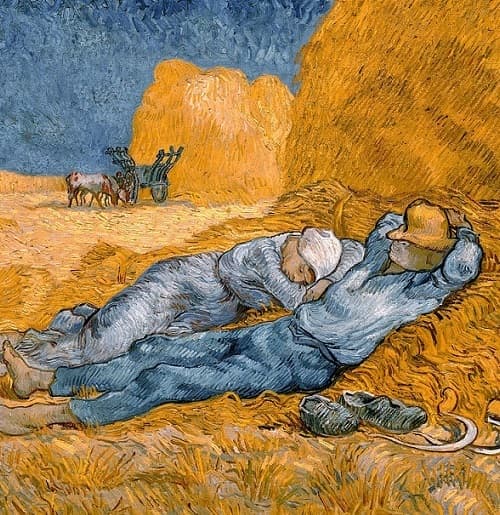

If the first page of the

Book of Genesis presents God’s “work” as an example for man, the same is true

of God’s “rest”: “On the seventh day God finished his work which he had done” (Gn 2:2).

Here too we find an anthropomorphism charged with a wealth of meaning.

It

would be banal to interpret God’s “rest” as a kind of divine “inactivity.” By

its nature, the creative act which founds the world is unceasing and God is

always at work, as Jesus himself declares in speaking of the Sabbath precept: “My

Father is working still, and I am working” (Jn 5:17). The divine

rest of the seventh day does not allude to an inactive God, but emphasizes the

fullness of what has been accomplished. It speaks, as it were, of God’s

lingering before the “very good” work (Gn 1:31) which his hand has

wrought, in order to cast upon it a gaze full of joyous delight.

This is a “contemplative” gaze which does not look to new accomplishments but

enjoys the beauty of what has already been achieved. It is a gaze which God

casts upon all things, but in a special way upon man, the crown of creation. It

is a gaze which already discloses something of the nuptial shape of the

relationship which God wants to establish with the creature made in his own

image, by calling that creature to enter a pact of love. This is what God will

gradually accomplish, in offering salvation to all humanity through the saving

covenant made with Israel and fulfilled in Christ. It will be the Word

Incarnate, through the eschatological gift of the Holy Spirit and the

configuration of the Church as his Body and Bride, who will extend to all

humanity the offer of mercy and the call of the Father’s love.

In

the Creator’s plan, there is both a distinction and a close link between the

order of creation and the order of salvation. This is emphasized in the Old

Testament, when it links the “shabbat” commandment not only with

God’s mysterious “rest” after the days of creation (cf. Ex 20:8-11),

but also with the salvation which he offers to Israel in the liberation

from the slavery of Egypt (cf. Dt 5:12-15). The God

who rests on the seventh day, rejoicing in his creation, is the same God who

reveals his glory in liberating his children from Pharaoh’s oppression.

Adopting an image dear to the Prophets, one could say that in both cases God

reveals himself as the bridegroom before the bride (cf. Hos 2:16‒24; Jer 2:2; Is 54:4‒8).

As

certain elements of the same Jewish tradition suggest, to reach the heart of

the “shabbat,” of God’s “rest,” we need to recognize in both the Old and

the New Testament the nuptial intensity which marks the relationship between

God and his people. Hosea, for instance, puts it thus in this marvelous

passage: “I will make for you a covenant on that day with the beasts of the

field, the birds of the air, and the creeping things of the ground; and I will

abolish the bow, the sword, and war from the land; and I will make you lie down

in safety. And I will betroth you to me for ever; I will betroth you to me in

righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love and in mercy. I will betroth

you to me in faithfulness; and you shall know the Lord” (2:18‒20).

“God blessed the seventh day and made it

holy” (Gn 2:3)

The

Sabbath precept, which in the first Covenant prepares for the Sunday of the new

and eternal Covenant, is therefore rooted in the depths of God’s plan. This is

why, unlike many other precepts, it is set not within the context of strictly

cultic stipulations but within the Decalogue, the “ten words” which represent

the very pillars of the moral life inscribed on the human heart. In setting

this commandment within the context of the basic structure of ethics, Israel

and then the Church declare that they consider it not just a matter of

community religious discipline but a defining and indelible expression

of our relationship with God, announced and expounded by biblical

revelation. This is the perspective within which Christians need to rediscover

this precept today. Although the precept may merge naturally with the human

need for rest, it is faith alone which gives access to its deeper meaning and

ensures that it will not become banal and trivialized.

In

the first place, therefore, Sunday is the day of rest because it is the day “blessed”

by God and “made holy” by him, set apart from the other days to be, among all

of them, “the Lord’s Day.”

In

order to grasp fully what the first of the biblical creation accounts means by

keeping the Sabbath “holy,” we need to consider the whole story, which shows

clearly how every reality, without exception, must be referred back to God.

Time and space belong to him. He is not the God of one day alone, but the God

of all the days of humanity.

Therefore,

if God “sanctifies” the seventh day with a special blessing and makes it “his

day” par excellence, this must be understood within the deep

dynamic of the dialogue of the Covenant, indeed the dialogue of “marriage.”

This is the dialogue of love which knows no interruption, yet is never

monotonous. In fact, it employs the different registers of love, from the

ordinary and indirect to those more intense, which the words of Scripture and

the witness of so many mystics do not hesitate to describe in imagery drawn

from the experience of married love.

All

human life, and therefore all human time, must become praise of the Creator and

thanksgiving to him. But man’s relationship with God also demands times

of explicit prayer, in which the relationship becomes an intense dialogue,

involving every dimension of the person. “The Lord’s Day” is the day of this

relationship par excellence when men and women raise their

song to God and become the voice of all creation.

This is precisely why it is also the day

of rest. Speaking vividly as it does of “renewal” and “detachment,” the

interruption of the often oppressive rhythm of work expresses the dependence of

man and the cosmos upon God. Everything belongs to God! The

Lord’s Day returns again and again to declare this principle within the weekly

reckoning of time. The “Sabbath” has therefore been interpreted evocatively as

a determining element in the kind of “sacred architecture” of time which marks

biblical revelation. It recalls that the universe and history belong to

God; and without a constant awareness of that truth, man cannot serve in

the world as co-worker of the Creator.

John Paul II served as Pope from 1978 to 2005.

He was canonized in 2014.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, The Surrender of Sleep.