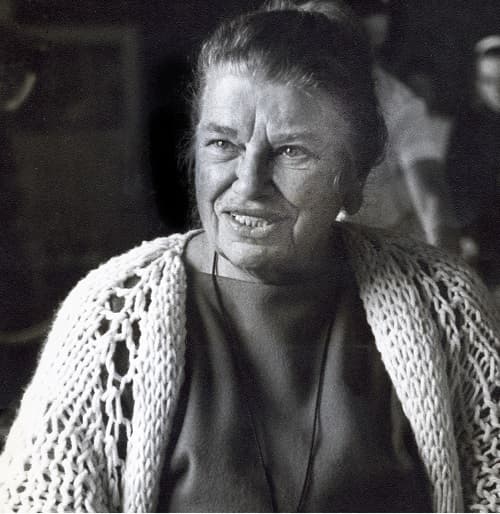

When Catherine de Hueck Doherty first thought of serving the poor in the slums of Toronto in the 1930s, she envisaged what she called “a poustinik way of life”—spending the mornings in prayer and fasting for the world, especially for the disadvantaged, and serving those in need in a direct way in the afternoons. (Poustinia is Russian for “desert” or for a place of solitary prayer; a poustinik is one who lives in the poustinia.) She would earn her keep by doing humble services, or taking enough work for her most basic needs, while living among the people she felt called to serve. For the way of life of a poustinik is not simply a life apart from the world, but a way of existing for the world and for its salvation. She was adapting to new circumstances in a New World different from the Russia she had left behind when the Communists took over in 1917. Different, but, given the severely depressed economy, not so much as to be invulnerable to atheistic communism and its glittering promise of economic transformation for the benefit of the poor and the working class.

Catherine intended to carry out this work with the blessing of her bishop—Neil McNeil, Archbishop of Toronto—as a lone apostle. However, things did not turn out as she had planned. She had been discussing her ideas in a small group studying the social encyclicals of the popes and some of its members now wanted to join her! Her enthusiasm for the Gospel was apparently infectious. Their wish presented Catherine with a great difficulty, for it seemed to directly contradict the very nature of the vocation she thought herself called to. She brought her dilemma to the Archbishop, who was to her mind (from her Russian Orthodox upbringing) the “father of her soul,” in order to secure his discernment. This very wise man told her she had a vocation 50 years ahead of its time, and that she should accept these five young people for the work that God evidently had in mind. For it seemed the Lord was aiming to start some type of new community that would be obedient to the local Ordinary, dedicated to living among and working for the disadvantaged, and remain entirely lay in nature. So much for the idea of poustinia. It appeared to be put on hold for the time being. But the original dream never left Catherine’s heart or consciousness. Always the longing remained for a form of solitude that was also at the service of humanity.

Now some 30 years have passed, and Catherine has been through many adventures and misadventures living community life at the service of the poor. The movement which was called Friendship House in those years had begun well in Canada and then suddenly collapsed through various circumstances and lack of support. Yet soon it began again in the United States, notably in Harlem, Chicago, and Washington, DC as a movement promoting principally interracial justice. Then came more difficulties, and this time Catherine was more or less ushered out of her own community due to conflicting visions of both the apostolate itself and the exercise of authority in the community.

In 1947 came a third try, this time back in Canada, in rural Ontario, in a little village called Combermere, about 200 miles northeast of Toronto. Within a few years the nascent community, called Madonna House, began to flourish, with missions to the poor thriving not only locally, but also in places as far-flung as the Yukon, Arizona, and Alberta. Membership was growing steadily. Virtually no one was expecting that in a very short time the Church would begin to go through years of massive change, renewal, and upheaval stemming from the Second Vatican Council. When Pope John XXIII made public his desire to call a council, Catherine sensed the need for prayer and fasting, because of the immensity of what was being proposed and the possibilities inherent in this for both good and evil. It was at this moment that she reached back into her Russian past and brought forth a word lying dormant for many years. That word was poustinia. She introduced the term to the community and invited them to begin to take time, perhaps one day a month, and spend it in prayer and fasting. This was becoming, in any event, a recognized necessity for lay apostles involved in an extremely challenging apostolate on-site and serving the poor. But she also saw it as a call to a more universal awareness of the needs of the Church and the world in a time of flux, change, and crisis.

Catherine herself began to spend time in an actual cabin which was simply called a “poustinia.” Other cabins were also built in order to provide space for the growing demand. And many guests who were coming to visit the community also wanted to take advantage of this time of silence, prayer, fasting on bread and water, and reading the Word of God. Here, at last, was the opportunity to live out more fully the original call from God, though not in the way originally understood.

It was not until 1975 that various teachings of Catherine about the poustinia were compiled, edited, and put together in a book by that name published by Ave Maria Press. An immediate success, it has since gone through several editions and been translated into a number of languages. But here’s the interesting and even strange thing about this book: It is written by someone who always longed to be in the poustinia but was prevented from doing so because of the demands of an extremely active apostolate. Even in the 1960’s, when time and space began to be available, she was taken up in the foundational years of teaching the spirit of Madonna House to its young membership. Yet she writes about the journey inward and its many aspects in such an authoritative fashion, one might think she had spent the previous 30 years or so in a kind of solitude, or at most, on the edge of society rather than some 25 years in such bustling places as Toronto, New York, and Chicago.

On the outside it appears her life was completely given over to the service of the poor and to the formation of Catholic laity. What kind of spirituality speaks of the interior life as central to faith yet never loses sight of suffering humanity with which it is often engaged in a direct and personal way? Is it possible to be actively involved in the heart of society’s struggles, and all the while be consciously journeying inward to meet the God who dwells within, drawing from that wellspring gifts of wisdom, compassion, and generosity for the sake of those in need? Or as Catherine put it: falling in love with God who was incarnate for our sake leads naturally to falling in love with human beings for whom the Son of God laid down his life.

I was far from understanding such talk, however, when I arrived in Combermere in 1972, a college dropout from Maryland.I came to Madonna House with a specific purpose in mind: to find out if Jesus Christ was real or not. I was a practicing Catholic. I ended up there because I wanted to be in a Catholic environment of some kind rather than a secular one. I was yet another seeker of that generation who through a variety of circumstances found his way to rural Ontario and to the community founded by Catherine Doherty. Very quickly I was plunged into the daily life of the community—communal prayer, meals in common and definitely not in silence (Madonna House is a very hospitable, talkative community), daily manual labour, some little free time for reading and recreation.

I first met Catherine Doherty during evening “tea-time” in a room that serves as a combination library, dining room, recreational space, and listening post. She was making her slow way, going from table to table, introducing herself particularly to the new guests, many of whom were in their early 20s like myself. My table was the last one she visited. She looked at me with piercing blue eyes that seemed to look at me, but through me to some far-off place, and then offered me a pamphlet containing a reflection she’d written on evangelical poverty. But I ignored the pamphlet and went straight to what was most important to me: “B (her nickname), in John’s Gospel Jesus says, ‘I am the way, the truth, and the life’; I want to believe it but I can’t. What should I do?” Her response was immediate. “Oh! You’re not ready for this yet,” and with that she took her poem on poverty and put it back in her basket. “What you’re asking about is faith. How does one come to faith? Sweetheart, that’s very simple. I’ll show you.”

With that this 75-year-old woman turned to the nearby wall, upon which was hanging an icon of the Lord. She made a sign of the cross, bowed deeply, and then lay prostrate on the floor before that humble image of Christ. She lay there, very still, for what seemed like an extremely long time. Then slowly, with the help of her cane, she got back on her feet and made as if to walk away, then turned, winked at me, and said, “A couple nights of that, and leave the rest to God!” Then she left the room. As time passed, I began to see, ever so slowly at first, the truth of her words. Humble oneself before God, and wait in patience, crying out to him. No other activity quite replaces it. And, yes, like nearly every other guest at that time, I wanted to go “into the poustinia,” that is, to spend 24 hours in one of those log cabins, alone with God, with nothing to read but the Bible and nothing to eat but bread. I did that. It was a good experience. I touched the reality of silence in a profound way, perhaps for the first time.

Through Catherine’s teaching, I learned to be alert to the word of God which might come while reading the Scripture in the poustinia. (It did from time to time.) But that was not all. The eternal Word of God is guiding all of life according to his mysterious purposes, and He makes his will known to us at any time or place He chooses—while working, walking along, while reading the sports pages, while getting dressed in the morning, driving a car—God can speak to us at any time. It is quite up to him!

Time passed. I joined the community, worked at the farm for a number of years as cheesemaker, and from there was sent to the seminary. After 35 very busy years of active ministry, I was allowed to enter the poustinia full-time, that is, three days “in” and 4 days “out” with the community. But long beforehand, I had begun to learn about “the poustinia of the heart” that deep place within one’s soul where God dwells. We usually don’t stay in that place for long; we are distracted and taken up with concern for many things, but the poustinia of the heart is always with us, always beckoning. I first discovered it the day Christ revealed himself to me at the centre of my deepest place of anguish. Suddenly, there He was, sharing my pain completely, filled with compassion and not with bitterness as I was at times. In his eyes the peace of a majestic king who has conquered the enemy and won a great victory. He was offering me a share in that victory, a pure gift of his love. And, yes, it was a cheesemaking day, so off I went to make the cheese, a changed man.

Now I become as one on fire with love of him and of all humanity across the world. Now it is not I who speak. I speak what God tells me to speak. When my immersion into his immense silence has finally caught fire from his words, then I am able to speak. I can speak because his voice is sounding loudly and clearly in my ears, which have been emptied of everything except him. Now only his name is on my heart, constantly; it has become my heartbeat.[1]

Father David May has been a priest of Madonna House for 38 years and living in poustinia since 2016.

[1] Catherine Doherty, Poustinia: Encountering God in Silence, Solitude and Prayer (MH Publications, 2000).

Keep reading! Our next article is Fit for Mission: Forming the Young in a Homeschooling Community by Marie Hansford-Jones.