Much has been written about how John Paul II’s Theology of the Body allows us to understand the truth of sexuality and conjugal love in our present sex-confused culture. But perhaps our enthusiasm for an effective catechesis has led to an overemphasis that obscures the full purpose of John Paul’s teaching. As Emily Stimpson writes in These Beautiful Bones: An Everyday Theology of the Body, “When we reduce the theology of the body to a theology of sex, we truncate the lessons John Paul II was trying to teach through those Wednesday audiences. We miss the point and narrow the scope. We end up with a theology with a rather limited application.” Life is more than sex. And sex itself can only be understood against the full horizon of life. John Paul II intended his Wednesday audiences to equip us against the reductive tendencies of modern life, to open the full horizon that illuminates the everyday, revealing redemption in the “normal tasks and difficulties of human life.” To help us experience this, Stimpson takes a simple and wise approach, focusing our attention not on the theology itself or its obvious immediate implications for conjugal life, but on the ordinary and everyday. Or as I described the book to a friend, it’s “Theology of the Body for real life.” The book is charming and approachable, but also deeply engaging and even provocative, the kind of read that generates more discussion than answers. It makes for an excellent introduction to the Theology of the Body for the uninitiated. But perhaps more significantly, Stimpson’s approach exposes a common error in our practical catechetics: the confusion of culture with catechesis, and the fruitless attempt to substitute the latter for the former.

Before detailing the virtues of the book and showing how it can correct some catechetical one-sidedness. I must confess that my initial reaction to the book was skeptical. A friend had proposed it for a parish reading group. I thought, “Do we really need another popular take on the Theology of the Body?” Without passing judgment on the merits of any specific example, I can say I have never been satisfied with popular presentations or pastoral applications of the Theology of the Body, which tend to follow two courses, both of which leave something to be desired: either (1) they end up merely re-presenting sexual ethics in new language, usually more palatable to a particular audience, or (2) they merely re-present John Paul II’s anthropology, albeit in clearer, less technical language. Of course neither of these are unworthy efforts. Certainly, the Theology of the Body has immediate implications for how we understand Humane Vitae, teach sexual ethics, prepare couples for marriage, etc. And, to draw out these implications, John Paul’s language and methodology certainly require some careful analysis and explanation. But it is the “merely” that leaves me unsatisfied. Both approaches stop short of what we need to translate John Paul’s catecheses into lived experience. And this seemed to be what my friend was seeking in our parish reading group: not something to study, but something to help us live our faith. Stimpson’s book, as we found, certainly answered that need, but it also helped me to understand the problem prompting my skepticism.

The problem in attempting to make the Theology of the Body “livable” is not a lack of technical competence with John Paul’s thought, but a misunderstanding of how theology informs lived reality. It’s the confusion between science and art. To think that we can teach our way into more holistic living, we ignore the pedagogy that underlies the Theology of the Body in the first place. God reveals Himself through the living, embodied communion of persons. We receive the truth of ourselves, as it were, by living this truth. The truth of man is translated through a living human culture. This means that we need to shift the conversation from the classroom to the space in which we actually live and work and eat and pray. This is exactly Stimpson’s proposal in These Beautiful Bones. We need to shift from catechetics to inculturation, that is, from understanding the teachings to living them creatively and holistically. Of course, no book or study course can explain to us what the Theology of the Body should look like in day-to-day life. And Stimpson does not claim to be able to tell us either. But she does start a conversation (between faith and life) that we can carry on for ourselves. And she does so first by choosing the most provocative starting point: this is not a book about sex, but rather about everything else!

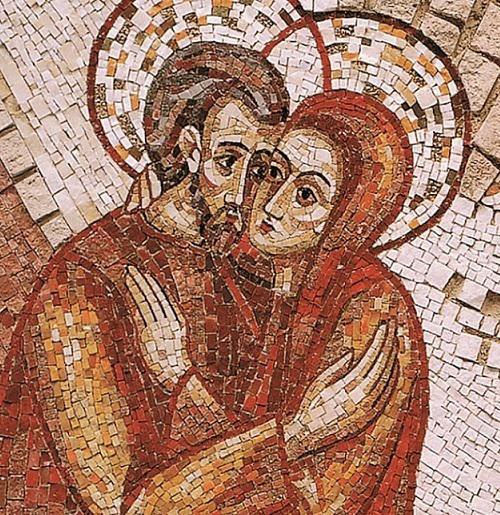

Even at first glance, the book is attractive and provocative. The title and cover art themselves speak volumes and can help us understand the distinction between catechesis and culture. Both involve cultural artifacts: the title refers to the Capuchin “bone church” in Rome, where the remains of thousands of friars have been artfully arranged in the crypt, which Stimpson insists is not so macabre as “strangely and overwhelmingly beautiful,” signifying thus the truth of the human body and its eternal destiny; the book’s cover presents us with Van Gogh’s study of Jean-François Millet’s “First Steps.” Both the Capuchin crypt and the painting of Van Gogh immediately communicate the truths expressed in the Theology of the Body, but without words. Stimpson tells us that John Paul II’s catechesis makes explicit what was known intuitively by the anonymous architects of the Capuchin crypt: what he says in words, they say in bones. Van Gogh also communicates without words, showing us the body as a sacrament of personal communion and the ethical criterion of human labor. These are, however, works of art, not theology, and the difference cannot be overlooked. To say that John Paul II makes explicit the truths implied in these works of art is only partially true. The truth is explicit, but not embodied; it is clear and distinct as abstraction, but not a living reality. To use Augustinian terms, catechesis is moving from things to signs: making explicit in words what is hidden in reality itself. Inculturation is moving from signs to things: embodying in living forms what is signified in words—the “language of the body” is expressed in how we eat together, dress and groom, give our attention to one another in conversation, attend to children, exercise, work, sleep. Catechesis without inculturation is still waiting to be embodied, made flesh. And culture without catechesis becomes opaque, forgetful of the deep truths that underlie its various expressions. To Van Gogh, Millet’s paintings were prophetic because they revealed something that even in the early days of industrialization had become obscured. They made explicit what lay hidden in the ordinary tasks of life: the theological significance of the body and human labor.[1] But they were works of culture, not theology. Much has been written over the past decades to help us to understand the biblical-personalist anthropology of the Theology of the Body, to de-mystify its language, and to draw out and apply its theological implications. But without a process of inculturation, we are ultimately left with only words, beautiful abstractions. Stimpson’s book is not a work of theology. But it’s not quite a work of culture either. It stands somewhere in between (between the theologian and the artist), in the space where theology becomes culture.

Theology doesn’t become culture by deduction. Inculturation takes place through a continuous dialogue between what we profess and what we live. These Beautiful Bones is an attempt to begin this dialogue. In the first two short chapters, Stimpson contextualizes and summarizes John Paul’s catechesis (an excellent digest in layman’s terms): “The theology of the body points the way towards new life. It shows us how, even in the midst of a culture that denies the meaning and dignity of the body, we can live lives that anticipate the fullness of redemption.” But then she takes that sorely needed next step: “So the question for us becomes, what does that life look like?” What follows are seven self-contained essays that develop this question towards salient aspects of modern life: (1) labor and leisure, (2) natural and spiritual parenthood, (3) social etiquette, (4) clothing and habits of dress, (5) food, (6) prayer, and (7) technology.

Three things strike me as particularly wise and helpful about her essays. First, while the Theology of the Body provides the foundation, she makes liberal use of observations drawn from social science, literature, and even popular culture. If our theology is true, then it should be verifiable from all angles. And because our theology roots us in reality, it does not dismiss, but rather amplifies other voices in concert with truth. Second, it is clear that what she wants us to examine critically against the light of theology is our own life, not “kids these days” or “the media culture” or anything else that we might employ to distance ourselves from the culture in which we do live, even if reluctantly. Certainly the Theology of the Body arms us against a culture hostile to the truth of our humanity, but it need not make us culture warriors. To live the Theology of the Body means first to recognize that we ourselves must be educated in this new humanity before we can have anything beautiful to hold up against those with a different vision. And third, the conversation she begins is always only that: a beginning that must be continued on our own. Each essay ends with a “postscript,” as if in the course of the discussion we were already anticipating a follow-up question: “The Theology of the Body tells us how to work, how to love, and how to dress. But does it tell us how to decorate our homes or organize our cupboards? . . .”

Stimpson’s essays model the kind of conversation we need to have, a kind of “kitchen table theology,” where a comparison can be made between what we presently live, even in the most ordinary moments, and what we profess. I call it “kitchen table theology” because it is there, at that intimate but communal space that we find the intersection of the various tasks of life. “Kitchen table theology” may not generate immediate answers, but it does move in the right direction by presenting the relevant questions. It is the first step in inculturation, that is, in translating our faith into culture. A “kitchen table theologian” does not preach so much as provoke by laying before our eyes the difficulties and sometimes glaring dissonance we encounter in our attempt to live the Theology of the Body. Stimpson points particularly to a “crisis of distraction,” fed by the ever-expanding pressures of media and information technology, which shows itself even in what we consider the most meaningful spaces of life:

Barely finding time to sit down and eat, let alone pray, exercise and spend leisurely evening in the company of family and friends, many of us feel as if we are sacrificing the most important things in life on the altar of perpetual busyness. And many of us are.

Is it possible for any of us live the Theology of the Body in times such as our own? “Possible? Yes. Easy? No.”

In my present work in seminary formation, I see firsthand the tendency to engage the Theology of the Body in a reduced way, without seeing its fuller implications for life. Many of my students, understandably, avidly search the Theology of the Body for language and concepts to frame their understanding of “virginity for the sake of the kingdom.” And they are not disappointed. But for all their enthusiasm, I wonder if they are not coming away with what Stimpson calls a “theology of rather limited application.” I worry about the young man who speaks fervently about how those called to virginity for the sake of the kingdom can nevertheless make an integral gift of self while spending his own Saturday nights binge-watching Netflix like any other young adult. In other words, my seminarian’s most pressing need is not an adequate language for understanding human sexuality, but a more humane relationship with technology and more regular manual labor. He would do well to follow Stimpson’s lead, not beginning and ending with sex, but widening his view to the ordinary and mundane where the “language of the body” has become obscured. He, like the rest of us, needs a way to revive and relearn the language of the body in practice. The problem my students face is not so much moral or theological, but cultural incoherence. These Beautiful Bones speaks to that incoherence: even as it probes what is broken or dissonant, it helps us to search out and hold before our eyes what is beautiful.

[1] His first experience of Millet’s works was nothing short of mystical: “When I entered the room in Hôtel Drouot where they were exhibited, I felt something akin to: ‘Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground’” (Letter to Theo van Gogh [29 June 1875]).

Samuel Fontana is a priest of Lafayette, Louisiana. He currently serves as parochial vicar of St. Joseph parish in Rayne. Prior to ordination, he studied philosophy at the Catholic University of America and theology at Mount St. Mary University in Maryland.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Making a Case for Humanae Vitae.