As children, we are fascinated by animals: the little bugs on the sidewalk, the squirrels in the trees, the dogs we meet on the street. What little child hasn’t had a favorite animal, some creature with which he or she becomes fascinated, and for which he or she has great affection? How many times have you seen a child stop in his tracks in order to observe a slug in the garden, or a worm on a sidewalk after it rains? This intrigue with our creaturely neighbors seems entirely natural: children have an inborn love of animals.

And yet, flash-forward ten-odd years in a child’s life to high school biology, and this wonder and awe for our fellow creatures has waned. Not many of my classmates cited biology as her favorite subject—in fact, almost none did; and I am certain that my experience in this area is not unique. Could it be that the way we study animals, or approach the very subject of biology, is flawed? Intuitively, we expect that biology, the study of life (βίος, in the Greek), would build on our natural childlike fascination. Yet, this is not normally the case. The formal study of life more often begins with cells and their parts, the so-called “building blocks” of life, rather than the study of the wholes that in fact are alive. Though not the case for everyone, this switch tends to repel amateurs—and I mean this in the literal sense of one who loves. Biology, as with so many of the natural sciences, becomes a realm of expertise; our childlike fascination wanes. And no wonder. When we study parts without first understanding the wholes whence they come, we lose any context for understanding the part. This is to say: we lose the reason the part is interesting in the first place.

Adolf Portmann, a professor of zoology at the University of Basel in Switzerland from 1931 to the late 1970s, offers a radically different approach to the study of animals—one which seems intuitive if we take a minute or two to think about it—but one which is not often presented as an option. Summarizing the book turns out to be quite difficult for me, a biology amateur, mostly because I find myself wanting to shove the book into the hands of anyone who will take it and say, “Here. Read this. Trust me.” I would forgive any skepticism on the part of my perhaps unwilling audience, given the book’s unassuming title (and even more unassuming subtitle: “a study of the appearance of animals”), but after reading this beautiful and insightful little book, I’d be surprised if others were not also impressed by the joy and delight expressed by the author for his subject. Animal Forms and Patterns is a gem of a book that gives its reader the eyes to see a world that has always been open to us, but is too-often ignored.

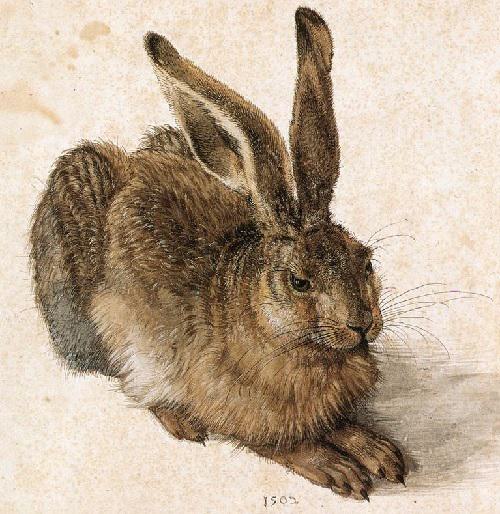

Given that the book, as its subtitle states, is a study of the appearance, or the morphology of animals, it may surprise the reader to find in it no photographs whatsoever, other than detailed drawings of every animal referenced. Photographs, though worth a great deal, do not necessarily require the observer to stay with a subject as a drawing does. The drawings are indeed indicative of Portmann’s principles: he asks of his reader (and himself) a careful and patient attention to the task at hand, which is first and foremost observation. “To observe,” he writes, “means to study every detail lovingly” (23). This is not poetry, but rather, the “first principle” of Portmann’s scientific method.

Portmann presents his thesis early: the forms of animals are made to be seen, and we should study them with this in mind. We’re not used to thinking about our world in this way for various reasons, but through patient observation and description—through which his clear love of animals and their forms shines—Portmann makes his case. We tend to think of organisms evolving over time with no interaction with or regard for the rest of the world unless through the forces of scarcity and overpopulation, but this hermeneutic tends to leave a lot of questions about animal form and structure unanswered. The fact that all animals are organized in such a way as to be intelligible is not in fact self-explanatory: Portmann remarks that “what is more delicately organized is always in greater danger” (67), and yet, we consider animals more advanced, evolutionarily speaking, if they exhibit more organization, both internal and external. Compare for example, the orca—considered to be one of the smartest animals on the planet—with its fellow ocean-dweller, krill. The orca’s advanced organization—brain, lungs, heart, etc.—could simply be a liability, if the only point of the animal’s existence were to pass on its genes to the next generation, as these higher organizational structures makes it much more vulnerable to injury. Surely krill, with much shorter generations and much less complicated morphological structures, could be said to beat out the less-efficient killer whale with respect to adaptation and fitness. And yet we all know intuitively that the killer whale is a more advanced animal in every way. Indeed, if “survival of the fittest” were the only force at work in the development of animals, most of the morphological structures we encounter would be entirely unintelligible. To be clear, Portmann is not presenting a denial of the theory of evolution, rather he is suggesting that by interpreting animals first and only through the principles of adaption and fitness, we will likely miss most of the knowledge and understanding about our world any creature has to offer. The zoologist draws our attention to the sheer aesthetic power of the world we live in, a force often ignored in pursuit of so-called practical knowledge.

A question Portmann asks that seems obvious after he asks it, but probably has never occurred to us: why does the outward appearance of an animal look so radically different from its internal organization? Our innards, as we all know, aren’t all that much to look at, but we know this not to be the case for the outward form of almost any animal. It seems, says Portmann, that the outer structure of an animal has been formed with a view toward being seen, whereas the internal organization takes its shape only from the rule of maximum efficiency. Internal structures, especially in the higher animals, do not belong to “the special sphere of what can be seen by the eye” (109). Portmann is suggesting here that the external organization of animals have a largely sematic function—this sematic component is what accounts for the difference between inside and outside in most animals. Another question: why is the contrast between “the outside and the inside” that much greater the more an animal becomes organized? If we pay attention, we see that the higher an animal is on the chain of being, the more contrast there is between its appearance and its internal organization. There is more difference, for example, between the outside of an elephant and its innards than the outside of a jellyfish and its innards. The higher the animal, Portmann suggests, the more it has possession of itself, or its own interior world, which is expressed through its morphology, whereas lower creatures do not possess such interiority and therefore have no need for their outside to be all that different from their inside. Thus, just by paying attention to morphological patterns, we are able to show the difference between an animal having an “inside” and an animal having an “interior life.” The latter is hidden from us unless we have the eyes to see it, while the former is accessible even to the most oblivious of observers. Portmann writes: “we shall perceive that the appearance which meets the eye is something of significance and shall not allow it to be degraded to a mere shell which hides the essential from our glance. We would not wish to be like grubbers after treasure who have no suspicion that the really valuable things can be found anywhere but hidden away deep in dark places” (35).

Portmann traces morphological patterns up and down the chain of sentient being, and as one reads the book, he slowly and beautifully gives his reader the capacity to see with his eyes, to become attuned to the morphological structures of animals and what they might indicate. The more advanced the animal, for example, the more symmetry the animal has. Even creatures too small for the human eye to see—such as Portmann’s favorites, the sea-dwelling Radiolarians—are organized around some type of symmetry. As we move up to the forms of higher animals, we see a switch to bilateral symmetry similar to humans. This switch that is not, by the way, mirrored in the internal organization of an animal, another piece of evidence that efficiency is not the last say in the animal kingdom. The bilateral symmetry of the higher animals is, it seems, made to be looked at by something (or someone) with two eyes, someone or something that recognizes and can understand bilateral symmetry. “What is made to be looked at, what is apparent to the optic sense, may be formed in a different way from those parts on the body of the same animal which are hidden” (109). Though efficiency does seem to be the standard when it comes to the internal organization of an animal, it is symmetry that rules the day when it comes to its pattern and form. It is indeed symmetry itself, Portmann surmises, that indicates to us that something is alive.

Another striking similarity across the animal kingdom: if the animal has a head, it is almost always the case that its patterning emphasizes this feature. Take a second to think about this: the small house fly, the bearded dragon, the tiger in the jungle—not just different species, but species on entirely different branches of the taxonomic tree—have a similar patterning structure. This emphasis on the head, says Portmann, again suggests the distinctly visible nature of creatures: it is as if these patterns are telling us where to look in order to understand the organism in its entire context, in order to understand the organism as a whole. The head is an animal’s organizing principle; the head shows us, and other creatures, where and how to look at the animal.

All of Portmann’s observations lead him to one main principle: that animal morphology is an expression of the “intensity of living” (108). It is the visible form, meant to be seen, that invites us into the knowledge that there is more to know, that life itself can be known. In other words, it is visible form that allows us to see that there is anything to know at all. And isn’t this what the child intuits, when he stops to watch a bird the rest of us have passed over?

But we should ask the blunt question: who cares? Or more gently: why should we care? The science of biology has in large part been co-opted by either molecular studies of cells or genetics—both rightful subdivisions of biology, but neither certainly the main component of the study of life. This hostile takeover, I would argue, succeeds only in alienating us from the rest of the world, rather than trying to accomplish the natural end of the natural sciences: knowing and loving the world. Looking at life through the lens of genetics makes us feel as if we are in a world of sterility and precision rather than the vibrant dynamic world in which we actually live.

We do not, however, study the forms and patterns of animals to make us feel less lonely—although there is something to be said for mankind keeping the knowledge of his stewardship for creation foremost in his mind—we also study life to know more about ourselves. The standard argument against the kind of science Portmann proposes is that it is useless, but I reject this thesis, as I think Portmann would. In fact a simply genetic biology in itself is useless, because it gives us no context for any information we may obtain, no way to order it. “Whether we are able to understand the play which is being enacted before our eyes depends upon other requisites than a grasp of the technique of the performance,” writes the Swiss zoologist (164). Seeing the play as a whole helps us to understand our place in it, but for this we must observe the world, lovingly.

Rachel M. Coleman is a Ph.D. Candidate at the John Paul II Institute and an Instructor of Theology at DeSales University.