Caryll Houselander (1901‒1954) was a British Catholic writer and artist who lived during the first half of the twentieth century. She was also a mystic. As a single woman who lived through two world wars and a time of social upheaval, she exercised a further, hidden apostolate: to tend to troubled souls. The President of the British Psychology Society, Dr Eric Strauss, who sent a number of his patients to see her, summed up her therapeutic style with a simplicity that cuts to the core of today’s more convoluted mental health environment: “She loved them back to life.”

Coming from a dysfunctional background herself—her parents split up when she was a young child, and as she grew up she often had to care for her own deeply neurotic mother—Caryll drew on her early wounds in order to formulate a deeply Christian vision of the human person. She herself was the first to admit her own faults: socially awkward, yet finding it difficult to curb her own tongue, she started out as a self-conscious young woman and developed into an eccentric who didn’t suffer fools gladly. She smoked like a chimney and cursed like a trooper. And yet in front of human suffering she would pour herself out. Her correspondence gives voice to her warm-hearted and sensitive approach to anyone who approached her. Caryll’s primary vocation was to spiritual motherhood. And this is particularly interesting for our own age, given that she was neither married nor a mother, nor did she live the consecrated life as conventionally understood. She adored children (and helped to raise the grand-daughter of her closest friend), yet she never had any children of her own.

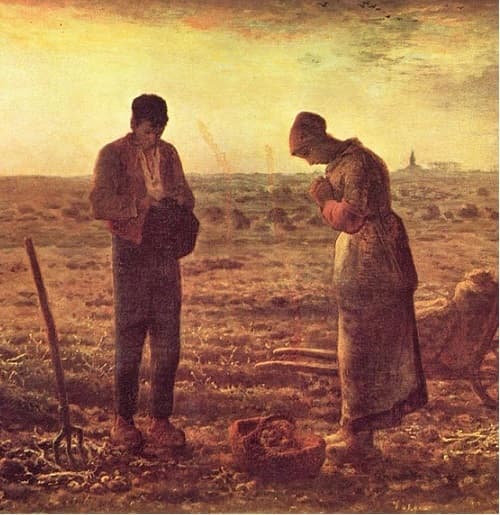

Caryll also had a very powerful sense of the dignity and meaning of human work, both professional and domestic. She began her career as a wood carver, working on church decoration among other commissions. She also drew, wrote poetry and eventually became known as a spiritual writer whose influence was far-reaching, particularly during the stress and duress of the Second World War, when her best-selling book This War is the Passion was published by Sheed and Ward. All of this in between working in first aid posts, schools and asylums, as well as corresponding with and visiting an increasingly large circle of people who depended on her for comfort and advice.

Having struggled to make ends meet as an artist and writer, Caryll was particularly sensitive to the problem of the cash-strapped who had no one to fall back on. During the depression of the 1930s, being for once fully employed (she was working for the interior decoration firm Grosse), she formed with some friends a secret society, The Loaves and the Fishes. The idea was to identify, and then help, people who were in financial need, but unwilling to ask for assistance. The interesting aspect of this was the creativity and sensitivity with which the help was brought to bear. As much as possible, the recipient was made to feel that he or she was not being treated as a charity case. Ways would be found to make it look as though the money given was a windfall, the result of a competition, or with people lined up to ‘buy’ the things that the person was able to produce. A strong sense of the dignity of the human person lay at the heart of the whole apostolate.

Whether she was creating something beautiful with her hands, or helping to reshape a life that had been knocked off-course, Caryll’s efforts were always imbued with a sense of proportion and beauty: things that would bring Christ, as naturally as possible, to the human environment. In the pre-war years she would work, and receive guests, in an unheated shed at the bottom of her friend Iris Wyndham’s garden. A visitor to this tiny fastness recalled the scene: “Lit by the lamp, her finely articulated hands appeared curiously transparent, utterly capable in an innocent and effortless way: when not holding a pencil or graver she relaxed them and they lay quiet, slightly flexed on some scrubbed surface of plain wood or a sheet of paper.”

These were the same hands that, metaphorically, she would apply to that other creative medium: that of the human soul, province of a greater Creator. Her genius for friendship overflowed into a work that of necessity was hidden and unquantifiable, and yet improved the quality of life for many whose lives had been destroyed by displacement, trauma and the myriad spiritual and psychological wounds of their age. The work, for this semi-eremetical eccentric, was made possible only by faith: a faith that had in fact been severely challenged early on in her life. Caryll had been received into the Church at the age of six, alongside her mother and older sister—making her what she called “A Rocking-Horse Catholic” (which became the title of her autobiographical memoir). But in her late teens, during a time of great strain at home, she experienced the worst side of parish life, which a final stinging experience whilst trying to attend Mass in a wealthy area of London brought to a head. She ceased for a while to be a practising Catholic, though she never let up on her spiritual quest. Having experienced a spiritual rebirth after some mystical experiences in her twenties, Caryll was henceforth possessed of a profound and sacramental Catholic faith which was also capable of understanding the travails of the disaffected soul. Her empathy for this kind of suffering is what turned her into the ‘wounded healer’ whose genius men like Dr Strauss recognised. Of her first such experience, counselling a refugee child, she wrote:

I am able to put into practice all my theories about psychology and I have great hope that from our poor little shed and this one strange lovely boy, our wisdom school may really begin. Pedro has a mind like a beautiful valley, almost hidden by a dark and shadowy twilight. In that twilight one hears the sound of tears and yet finds rare and isolated flowers growing, and these flowers have a positively sparkling brilliance.[1]

The work grew from there, and it truly absorbed her.

I don’t exaggerate, with these children I suffer myself, you can’t help them if you don’t. To give all my spare time to them seems silly, but you have to (I mean, I have to) … You have to share their sense of defeat, shame and so on, go with them step by step through the dark valleys, and bring them out again to the light.

As these words reveal, one of Caryll’s strongest qualities was her imagination. Her writing, which developed into her primary professional focus, is imbued with this gift. “I am a drain pipe,” she wrote. “God wants to pour words through me.” Imagining herself into the daily life of the Holy Family, for instance, gave her a taste for the tenor of a life lived between manual labour and the communion of souls. Some of her most beautiful writing was done in the form of what she called ‘rhythms’ (she hesitated to call them ‘poems’). Her classic book of Marian spirituality, The Reed of God,is also imbued with this poetic voice, a voice which makes the reader enter into the very essence of what it means to be a bearer of Christ into the world, modelled on his own mother. Here her psychological astuteness meshes with the scripturally-based material, as for instance when she ends her meditation on the meaning of Advent, and Mary’s pregnancy, with the following counsel:

If we have truly given our humanity to be changed into Christ, it is essential to us that we do not disturb this time of growth. It is a time of darkness, of faith. We shall not see Christ’s radiance in our lives yet; it is still hidden in our darkness; nevertheless, we must believe that He is growing in our lives; we must believe it so firmly that we cannot help relating everything, literally everything, to this almost incredible reality. This attitude it is which makes every moment of every day and night a prayer. In itself it is a purification, but without the tense resolution and anxiety of self-conscious aim.[2]

Caryll was always something of a freelancer. She took work as it came along, had to rely on the shelter and charity of others in hard times, and dispensed the same when her fortunes turned. She was wary of formal ecclesial organisations, which she felt might get stuck in their own ‘charism’ and distract its adherents from spontaneously responding to the here and now of daily circumstance. Any formal organisations she got involved with, such as the Grail Society, had to accept that in the long term she could not be contained within their boundaries. She liked to respond to the Holy Spirit as personally as possible. As Maisie Ward put it in her biography of Houselander (That Divine Eccentric):“It is the paradox of the Gospel: to work secretly, looking only to ‘the Father who seeth in secret,’ yet to let our ‘light shine before men.’ It is the problem of the Church itself, which after all was founded by Christ to gather in all the world, yet to reject worldiness” (114).

And yet she had a keen sense of economic realities, and reflected on the question of what Christian work consisted in. A letter written to her friend Archie Campbell-Murdoch, who converted partly under Caryll’s influence, and who wanted to participate in her apostolate to refugee children, makes some interesting points about the relationship between work and Christian charity.

I think, if I may be frank, that you should disabuse your mind completely of the idea that an action or way of life loses its supernatural value because it is a means to your livelihood, because you are paid. The idea that only unpaid work is real charity (love), is simply a snobbish idea which grew fat under the Victorian worldliness: it is not the Catholic idea. To start with, the idea is that everyone should work,and that their work, which ought to occupy most of their life and all their best energy and ability, should be in itself the chief means by which they give glory to God—that means that their whole-time job should be their holiest and most charitable self-offering. If they are not able to find work that fulfils that ideal, they are crippled their whole life long.

To say that charity is only what is not paid for, and not a means to living, is the same as saying that the only people who can fill their lives with charity are the rich—the few exceptions, to be pitied, who need not earn their living; or alternatively that the poor and the huge majority who do have to work can only really glorify God in their spare time and when, in all likelihood, they are tired out and have only a fifth best to offer. Our Lord says, even in respect to the work of being Apostles, “the labourer is worthy of his hire,” and He specifically told His Apostles to accept board and lodging in return for their apostleship. He Himself was a workman, and He did not give away the things He made; He took pay for them and helped to support His home and family.[3]

The complexity of these questions was experienced keenly by Houselander herself. In the forties, for example, she struggled to balance the needs of her growing vocation to write, against those of the people who needed her on a more immediate plane. During the war, she was working incessantly for others both day and night (by day she was nursing, by night she was on fire-watch duty as German bombs fell all around her, learning to embrace her own terror as an identification with the suffering of Christ). Yet she was also trying to write. Iris Wyndham, who at one point during the war shared a one bedroom flat with Caryll and another woman, described how she struggled to fit her writing in around the needs of others.

Night after night she would write till the pen fell from her hand. Yet she never held back: she gave everything she had. Everyone felt they were the important person. Coming into the flat and finding someone who would make a demand on her she would stand stock still as if she had been shot. It would be at least ten minutes before she could speak coherently.[4]

People who had got to know her through her writings or her outreach work would knock on her door and ring the bell, and if she didn’t answer go on knocking and ringing… “I am harassed by people as well as by bombs,” Caryll admitted.

Her year working at the first aid post was succeeded by a posting to censorship. Her department was next to the Air Force Division. Even here the double level of her work—professional and spiritual—came out: a non-Catholic Flight Lieutenant who had got to know her began to depend on her prayers. To the slight irritation of her superiors, he would “appear round the cupboard separating the two sections with his hands prayerfully folded, mouthing ‘a genoux!’.”

There are countless examples of how Caryll evangelised through her presence in the midst of the world and of people who did not necessarily share her religious perspective. Like the fiery Dominican preacher Vincent McNabb, who inspired the early 20th century back-to-the-land movement, she was always willing to make a fool of herself for Christ. She was keenly aware of the moods of those around her. At one point she suggested a typically humorous way of brightening up the days of people sitting on the bus with her. You could simply sit there, she said, and make slightly strange faces. This would have the purpose of distracting people from their own problems, whilst at the same time making them feel grateful for being much more normal and attractive than you are. Even in the midst of the madness that was London in the Blitz, this particular manifestation of concern for one’s fellow man must have taken a great deal of humility!

Under the high jinks and ready repartee (“Houselander,” demanded her nursing matron one day as they prepped hurriedly to receive a batch of wounded civilians, “Are you sterile?” “Not so far as I know!” quipped the spinster in return), Caryll was of course in deadly earnest. She had enough experience of evil, both in her own soul, and in that of others she knew of, to be consumed, as was her medieval counterpart St Catherine of Siena, with a zeal for souls. What made her unusual, and perhaps particularly modern, is the great empathy and humanity she brought to that task. She was also realistic about her own limitations, something that anyone who does this kind of hidden work for Christ really needs to be. She was particularly aware of the dangers that beset pious single women. This was her commentary on the parable of the wise virgins.

Unfortunately, there are not only wise virgins in this world but unwise ones; and the foolish virgins make more noise in the world than the wise, giving a false impression of virginity by their loveless and joyless attitude to life. These foolish virgins, like their prototypes, have no oil in their lamps. And no one can give them this oil, for it is the potency of life, the will and capacity to love. Virginity is really the whole offering of soul and body to be consumed in the fire of love and changed into the flame of its glory.[5]

Much as she herself wanted to offer herself soul and body to Christ and to his needy children, as she got older and her health failed (she died of breast cancer at the age of 53), Caryll Houselander had to limit herself to one aspect of her vocation: the one that gave posterity access to her wisdom. She poured her last years into her books. Confiding to another writer who asked her about whether it was a bad idea for a writer to socialise, she wrote revealingly about this period of her life:

I find that my vitality is exhausted and that I can no longer cope both with people and with writing, and I am certain that for me the real communion with people is in writing, and this does not only apply to strangers but to my intimate friends; I have realised that when they keep me from writing, they are actually destroying all hope of communion between us. With you, however, it may be otherwise; social contact may be a necessary stimulus.[6]

Of one thing she was sure, however. For the Christian artist, the ego has to be mortified. “If one’s work is to be a communion with humanity, then one has to suffer for it; one has to suffer seeing its imperfections, for one thing. After all, our work is ourself, and this being so, we can be certain that it will never be perfect.” Curiously, her only novel, The Dry Wood, bears this out. Far from a perfect work of art, it is nonetheless imbued with all of Caryll’s central concerns: the dignity of the poor, the salvific impact of weakness and disability, of the vulnerable, the child, the mysterious presence of Christ at the heart of every human drama. Her art lay in meditation, without artifice.

And so far from taking herself too seriously as a creative artist, Caryll of necessity fell back on those day to day tasks that St Thérèse, to whom she had a devotion, held onto, and she never turned her back on those relationships which at times also tried her. This she wrote to a friend who had sent her some cleaning materials for her first little solo flat (dubbed the KitchMorgue, because it was so tiny and looked out onto a dark well between buildings):

I have more and more realised since I had the KM how real the prayer of contemplation is that consist outwardly in washing up, dusting and cooking; and to have thee mops and dusters and clothes to make even ‘the outward and visible sign’ of it beautiful, and to have them from you is a delight.[7]

Here we have all the aspects of Caryll’s ‘work’ in unison: the beauty of domestic labour, the attention to the human. Whether it was unseen and unsung, or out there in the professional world, Caryll believed that the best work for a human being was the “one which will enable him to serve God best and be, in itself, as work should be, a means of contemplation.”

Of course, she did not mean a contemplation that sets itself apart from the human suffering in our midst. Christians addressing this “must set their pace to the footsteps of a crippled world… For every 1000 women who can now dress a wound on the flesh, there is only one—if as many—who can begin the healing of a wound in the mind. It requires much more education to attend to a broken heart than it does to attend to a broken leg.” In order to do this we must pray. We must allow prayer to break us. We allow Christ to grow in us, to take us beyond our comfort zone. “We have to stretch Christ in us… the cross overshadowing the whole world… The arms of Christ stretched on the cross are the widest reach there is, the only one that encircles the whole world.”[8]

[1] Maisie Ward, That Divine Eccentric (Sheed and Ward, 1962), 188.

[2] The Reed of God (Sheed and Ward), 29.

[3] Letter to Archie Campbell-Murdoch, December 24, 1945 (from The Letters of Caryll Houselander [Sheed and Ward], 59).

[4] That Divine Eccentric.

[5] The Reed of God, introduction, 2.

[6] Letter to Christine Spender, January 21, 1946 (The Letters of Caryll Houselander, 101).

[7] That Divine Eccentric, 184.

[8] Ibid., 192.

Léonie Caldecott is the UK editor of both Humanum and Magnificat. With her late husband Stratford she founded the Center for Faith and Culture in Oxford, its summer school and its journal Second Spring. Her eldest daughter Teresa, along with other colleagues, now work with her to take Strat’s contribution forward into the future.

Keep Reading! The next article in the issue is, Work and Monasticism by Dom Benedict Hardy OSB