The medicalization of dying and the disregard for the life of the soul within contemporary health care prompt the return of the Ars moriendi, or The Art of Dying (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2022). This widely influential fifteenth-century text was designed to guide dying persons and their loved ones in Catholic religious practices at a time when access to a priest and the sacraments was similarly limited.

One of the foremost points made in the Ars moriendi is that the experience of dying can sorely test a person’s faith in God and in the promise of salvation. There is a natural tendency for individuals who are suffering on physical, psychological, and spiritual levels to seek out bodily remedies and psychological reassurances above what the Ars moriendi calls “spiritual remedy and medicine.” What was clearly a problem in medieval times, with their limited medical capabilities, must be seen as an exponentially greater and more complicated one today, with all the health care options available to people as they approach their final days. The Ars moriendi indicates that it is best to prepare well in advance for this trying experience—that the art of dying needs to be cultivated and reflected upon. As a result, one of the greatest challenges and responsibilities for the Church today is to determine how best to guide the faithful in their preparations for death, whether near or remote.

An excerpt from the Ars moriendi follows and is reprinted here with permission:

Although according to the Philosopher in the third book of the Ethics, “Of all terrible things, the death of the body is the most terrible,”[1]

this is not at all comparable to the death of the soul. Consider Augustine, who says, “The loss of a single soul is worth more than that of a thousand bodies,”[2] and Bernard, who says, “All the world combined does not equal the value of a single soul.”[3] The death of the soul, then, is more to be feared and despised inasmuch as the soul is nobler and more precious than the body. The devil also knows how precious the soul is, and so he assails the dying person with the greatest temptations in order to secure his eternal death. Hence, it is of the utmost importance for the dying person to tend carefully to his soul, so it will not perish at the time of death.

For this purpose, everyone would greatly benefit from having frequently before their eyes the art of dying well—the focus of this work—and to reflect upon their own final illness. As Gregory says, “Whoever bears in mind his end rouses himself strongly to doing good works.”[4] For a future misfortune is more easily tolerated if considered in advance, as it is said: “When future things are foreseen, they are more lightly borne.”[5] But very rarely do people dispose themselves for death in a timely manner; rather, they expect to survive a while longer and in no way believe they could die soon—a thought instigated, no doubt, by the devil. For many, through such foolish optimism, have neglected themselves and died unprepared. Be on guard, then, not to allow the sick to be deceived into having unrealistic expectations of recovery. For according to the Chancellor of Paris, “Often through such false consolation and unrealistic confidence in their health, [dying] persons run the risk of incurring damnation.”[6]

Let the one approaching death... know that Christ died for him and that there is no other way he can be saved except by the merit of the Passion of Christ, for which he should give thanks to God as much as possible.

Before all else, therefore, let the one approaching death be guided through the things necessary for salvation:

First, he should believe as a faithful Christian does, and even rejoice, that he will die in the faith of Christ and the Church, united with them in obedience.

Second, he should recognize that he has gravely offended God and grieve because of it.

Third, he should resolve that if he recovers, he will amend his ways and never sin again.

Fourth, he should forgive those who have offended him, for the sake of God, and ask forgiveness from those he has offended.

Fifth, he should make restitution for the things he has taken.

Sixth, he should know that Christ died for him and that there is no other way he can be saved except by the merit of the Passion of Christ, for which he should give thanks to God as much as possible. If he is able to assent to these items with a sincere heart, it is a sign that he is to be numbered among the saved.

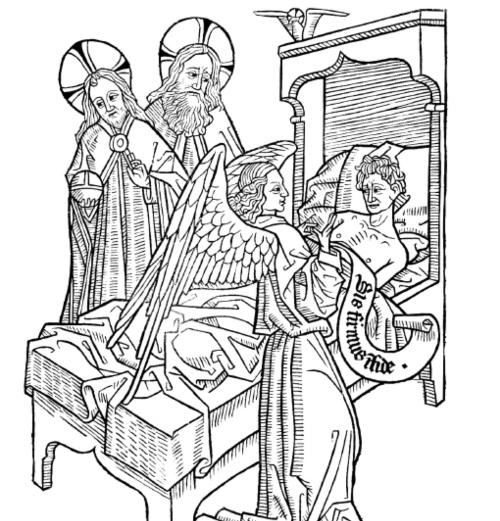

Then he should be carefully led to receive the sacraments of the Church with faith and reverence. First, with true contrition, he should make a complete Confession, receiving devoutly the other sacraments of the Church in turn.[7] Whoever has not been asked or informed by another regarding the above items, let him examine himself to consider if he is disposed as indicated. Whoever is thus disposed, let him commit himself entirely to the Passion of Christ, holding fast to it and meditating on it. For through this, all the temptations of the devil, and especially those against faith, are overcome. It should be noted as well that the dying face graver temptations than ever before—and there are five, as will be shown later. Against each of these temptations, the angel offers good inspiration.[8] But so that all may benefit from learning the art of dying well, and no one is excluded from it, this work is intended for the eyes of all: with words to serve the literate and images to serve the illiterate and literate alike. The words and images correspond mutually, as in a mirror, in which past and future are beheld just as the present. Whoever wishes to die well, then, should consider carefully the things that follow…

[1] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, III.6.1115a26. Aristotle (384–322 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher whose work provided an important foundation for the development of Christian theology. Nicomachean Ethics is Aristotle’s most famous treatise on ethics.

[2] See Augustine, City of God, VIII.15. St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) was a monk, bishop, and perhaps the most influential Christian writer and preacher since the time of the apostles.

[3] Anonymous, Most Devout Meditations on Understanding the Human Condition, cap. 3, para. 3. This work was previously attributed to St. Bernard of Clairvaux.

[4] St. Gregory the Great (c. 540–604) was a monk, pope, reformer, and prolific writer who summed up the thought of the early Church and greatly influenced spirituality in the Middle Ages. The above quote may have been influenced by the Rule of Saint Benedict, written in 516, which states that one of the instruments of good works is “to keep death daily before one’s eyes” (chap. 4, n. 47).

[5] Pseudo-Aristotle, The Secret of Secrets, I.22.3. This work is of unknown origin, but it claims to be a letter from Aristotle to Alexander the Great and covers a wide variety of academic topics.

[6] Jean Gerson (1363–1429), commonly referred to as the Chancellor of Paris, was a priest, reformer, and theologian whose treatise, The Science of Dying Well, directly influenced the present work.

[7] Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: US Conference of Catholic Bishops/Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2016 update), nn. 1457, 1525. In the fifteenth century when this work was written—like today—believers did not regularly receive the sacraments. For dying persons, the Church presents a positive vision of Confession, Anointing of the Sick, and the Eucharist as three important sacraments that help us “prepare for our heavenly homeland.” More generally, the faithful are bound by the Church to confess serious sins at least once a year. Anyone aware of having committed a mortal sin must not receive Holy Communion without having received absolution in Confession, unless there is grave reason for receiving Communion and no possibility of going to Confession.

[8] The term “good inspiration” (bona inspiratio) is used throughout this work to refer to the effective, encouraging replies of the angel to help the dying person overcome the temptations of the devil.