The human condition is always the same, but different ages aggravate different symptoms of it. One permanent element of the human condition, symptoms of which are aggravated by the conditions of our own age, is articulated very clearly in one of the famous endnotes to David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest. Wallace describes his character Hal Incandenza as reflecting on his “curious feeling that he goes around feeling like he misses somebody he’s never even met.”[1]

Being given to abstract thought (as so many of Wallace’s characters are), Hal universalizes his feeling into the claim that “we’re all lonely for something we don’t know we’re lonely for.”[2] To Hal, loneliness is “the great transcendent horror,”[3] from which we are constantly trying to escape. Wallace’s characters seek innumerable ways of trying to escape their deep loneliness—plunging into anything which can make them forget the horror of “excluded encagement in the self.” This attempt to escape loneliness becomes a flight from the self, an attempt to find forgetfulness of self in diversion, pleasure, intoxication, business, or fanatical indignation (“A flight-from in the form of a plunging-into”[4]).

In his final, unfinished novel The Pale King, Wallace describes the flight from the self as a symptom of the perennial problem of human finitude. The Pale King records a number of IRS agents stuck in an elevator, and one of them goes on a long rant on the problem of finitude. “Time is always passing, and everything else is passing away with it like fuel in fire, never to return. Soon we will all be dead. Soon everyone who knows us, or even knows we exist, will also be dead. It will be as though we had never been”; this causes a “deep fear” that no one—except a few French existentialists and the early modern polymath Blaise Pascal— ever thinks about. In fact, “we all spend all our time not thinking about [it] directly.”[5] This fear is closely related to loneliness; if one does not matter, if one’s very existence will be forgotten, then one is alone.

The problem of human finitude, of mortality, is of course as old as man. Achilles’s rage in Homer’s Iliad can be understood as rage against his own mortality. Nevertheless, the way in which this problem is felt in Wallace is typically modern. Wallace’s reference to Pascal is significant. Pascal stands at the beginning of the modern age. In his Pensées Pascal describes the cosmic imaginary of persons who had fallen under the spell of the reductionism of Descartes and other early modern philosophers.

The medieval worldview which preceded them had integrated the finite human being into an organic whole that included human society, nature, and supernatural forces. The universe was seen as a finite, ordered whole, created by God. It was not an empty, indifferent space, but one in which the different parts related to each other. The various heavenly spheres were not silent, but musical, and they influenced human life. The picture of the world that we find, for example, in Dante’s Commedia, shows the order of the universe as formed by the Divine Reason (logos), and each creature as mirroring some aspect of that logos. Each creature has a principle of teleological action (a “nature”) that orders it to the whole. The order of the whole is seen as the greatest good of creation because it reflects the divine logos more perfectly than any particular part. All of the parts of the universe are bound together by a hierarchical order of governance working for the benefit of the whole, though disturbed by sin.

"In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshiping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship."

–David Foster Wallace

Human society is seen as part of this order, participating in this order. Human persons, in this view, could see themselves as playing a part in a communal cosmic project. They were to subordinate themselves to this order, and thereby be “unalone.” The “nobility” of the human person in comparison to the rest of creation was seen as stemming from his ability to attain to the good of the whole through knowledge and love and consciously subordinate himself to that whole. This ability to know the whole meant that the human soul was immortal. Human persons were, however, seen as “fallen” through “original sin” from an unproblematic integration into the whole. Sin to some extent alienated human persons from the cosmos and its creator and put them into a state of “dissimilitude” and sadness. Thus, it was necessary for them to be healed and reconciled to God and His creation, and this was a central aspect of the redemptive work of Christ. Finitude was thus solved by the gift of eternal life, and loneliness by the reconciliation and communion of that life.

For Descartes and other moderns, however, this view of the world disappears. Descartes sees the material world as a blank mathematical extension without teleology or interiority. It is wholly foreign to the thinking subject which is meant to dominate it through a new mathematical science. This is supposed to set humanity free from dependence on the cosmos, but it can also cause a feeling of vulnerability and abandonment—hence Pascal’s famous pensée: “The eternal silence of these empty spaces fills me with dread.”[6]

For Wallace, Descartes’s new form of mathematical science is the very essence of modernity. The new mathematical science that began in the 17th century is “what the modern world’s about, what it is.”[7]

Modern culture is “schizoid,” Wallace argues, because “[w]e ‘know’ a near-infinity of truths that contradict our immediate commonsense experience of the world.”[8] For example, “I ‘know’ my love for my child is a function of natural selection, but I know I love him, and I feel and act on what I know.”[9] The progress of mathematized science has led to “abstraction-schizophrenia and slavery to technology and Scientific Reason.”[10]

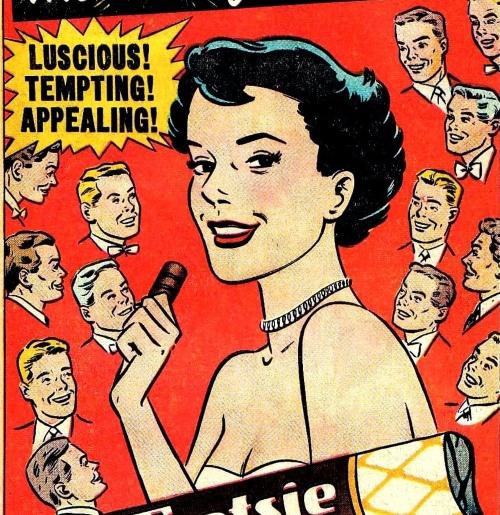

Wallace describes one of the great engines of such slavery as being the capitalist/consumerist economy enabled by technological progress. Capitalism exploits the meaninglessness of the modern world to make money. There being no natural teleology, an artificial teleology is engendered. “Demand” is stimulated by presenting products as the solution to the loneliness and meaninglessness of the world. In a capitalist economy, products are not developed primarily for the sake of fulfilling the needs implied by a definite understanding of a happy or virtuous life, a life lived in accordance with the slant of natural teleology. Rather, fake images of the happy life are generated to sell the maximum amount of product. The ease of arousing infantile and harmful desires and cravings means that corporations will have a special incentive for appealing precisely to those desires. In other words, it is not just that corporations are not ordered to fulfilling a true conception of happiness; it is that they are structurally inclined to create demand for goods that are an obstacle to true happiness. But since creating demand means persuading people that something is necessary for happiness, corporations are structurally inclined to promote false images of happiness.

Wallace was fascinated by advertising and continually described, parodied, and analyzed it in both his fiction and his nonfiction. A good example of the subtle suggestion that the indulgence of infantile desire contributes to happiness occurs in the story “Mister Squishy,” arguably Wallace’s fullest exploration of the manipulative nature of advertising. A fictional snack company, Mister Squishy, gives a new chocolate snack the name “Felonies!” The name is meant to suggest that happiness really consists in rebelling against the explicit notions of virtuous living current in society and imposed by the super-ego, conceptions that call for self-discipline and health-consciousness:

[A name] meant both to connote and to parody the modern health-conscious consumer’s sense of vice/indulgence/transgression/sin vis à vis the consumption of a high-calorie corporate snack. The name’s association matrix included as well the suggestion of adulthood and adult autonomy […][11]

The cleverness of the branding consists in the fact that while the cake is meant to stimulate an infantile desire for sweetness, a desire which at some level the consumer recognizes as infantile and wants to resist, it simultaneously overcomes that resistance by suggesting to the consumer (or the consumer’s subconscious) that giving in to the desire would not be infantile, but in fact adult, a sign not of surrender to clever advertising, but rather of autonomy. Different corporations are, of course, playing opposite sides of the game. On the one hand, advertisers promote as the model of human life an ideal of physical fitness unattainable by sedentary office workers, so other corporations can market all kinds of diets, diet-friendly foods, exercise aids, and so on to attain that unrealistic goal. And then, on the other hand, corporations such as Mister Squishy can take the opposite tack and promote self-indulgence:

[Enterprises…] that said or sought to say to a consumer bludgeoned by herd-pressures to achieve, forbear, trim the fat, cut down, discipline, prioritize, be sensible, self-parent, that hey, you deserve it, reward yourself, brands that in essence said what’s the use of living longer and healthier if there aren’t those few precious moments in every day when you stopped, sat down, and took a few moments of hard-earned pleasure just for you? and various myriad other pitches that aimed to remind the consumer that he was at root an individual, one with individual tastes and preferences and freedom of individual choice, that he was not a mere herd animal who had no choice but to go go go on US life’s digital-calorie-readout treadmill[…][12]

Wallace’s reference here to “freedom of individual choice” is ironic. The freedom in question is a fake freedom that amounts to a kind of slavery.

For Hal Incandenza, the brilliant teenager at the center of Infinite Jest, the ubiquity of the fakeness of advertising has led in American teenagers to the cultivation of an attitude of irony and cynicism, an attitude of seeing through the fakeness of all the promises of consumerist culture, and all the fake methods advertised for transcending that culture. “We are shown how to fashion masks of ennui and jaded irony […] the weary cynicism that saves us from gooey sentiment and unsophisticated naivete.”[13] But Hal recognizes that the attraction of this cynical attitude stems in large part from the fact that it is itself a fake means of escaping loneliness: “keep in mind that, for kids and younger people, to be hip and cool is the same as to be admired and accepted and included and so Unalone. Forget so-called peer-pressure. It’s more like peer-hunger.”[14] The teenagers learn this hip attitude from the most avant-garde

expressions of postmodern art. Postmodern because it sees through the fakeness of modernity, but also hypermodern (to borrow Gilles Lipovetsky’s term), because it offers no escape from the structures it mocks. Hal Incandenza consumes the products of American capitalism ironically, but he nevertheless consumes them. Moreover, the ironic distance from the world closes off any avenue of escaping his existential loneliness. He can only speak of connection between persons, of love, of transcendence, or meaning, in an “ironic” mode that is meant to show that these ideas are seen to be shams.

Mario Incandenza, Hal’s special-needs brother, completely lacks this ironic distance from the world, and he is disturbed by seeing it in others. He is puzzled that people cannot talk about deep emotions, or about suffering or loneliness, or God. “It’s like there’s some rule that real stuff can only get mentioned if everybody rolls their eyes or laughs in a way that isn’t happy.”[15] This culture of ironic distance makes its practitioners deeply lonely. Hence the one emotion that Hal sees himself being able to really feel to the limit is loneliness.[16]

Is there any answer to the terrible loneliness of the human condition, so aggravated by the conditions of hypermodernity? One of the most hopeful characters in the novel is precisely Hal’s brother, Mario. Mario visits Ennet House, a half-way house for recovering drug addicts:

Mario’s felt good both times in Ennet’s House because it’s very real; people are crying and making noise and getting less unhappy, and once he heard somebody say God with a straight face and nobody looked at them or looked down or smiled in any sort of way where you could tell that they were worried inside.[17]

The people in Ennet House say “God” with a straight face, because they have come to the end of their tether and are willing to try anything to help them escape their addiction. They attend 12 step programs which tell them that they need to entrust themselves to a higher power. To the surprise of many of them, this actually works.

In 2005 Wallace gave the commencement address at Kenyon College. In his address Wallace talks about the flight from the self into diversion as a form of worship, an idolatrous, self-destroying form of worship:

Because here’s something else that’s true. In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshiping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of God or spiritual-type thing to worship—be it J. C. or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles—is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things—if they are where you tap real meaning in life—then you will never have enough. Never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly, and when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally plant you. On one level we all know this stuff already—it’s been codified as myths, proverbs, cliches, bromides, epigrams, parables: the skeleton of every great story. The trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness. Worship power—you will feel weak and afraid, and you will need ever more power over others to keep the fear at bay. Worship your intellect, being seen as smart—you will end up feeling stupid, afraid, always on the verge of being found out.[18]

Wallace’s deep insight into the human condition was indeed that we all go around missing someone whom we have never even met, lonely for the one from whom we have been estranged. And he saw that the flight into diversion is a symptom of that loneliness, a symptom that leads now in our hypermodern culture to the same place it led the ancient Israelites: enslavement to false idols. The idols have different names and better marketing, but they are idols nonetheless. Yet Wallace’s vagueness and hesitation about naming the one from whom we are estranged is a sign of how modernity aggravates our condition and makes it difficult even to name.

It has been 15 years since Wallace’s death by suicide. In those years the world has only come to resemble his novels even more closely. He is the preeminent diagnostician of our crisis of meaning.

[1] David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest (New York: Little, Brown, 1996) 1053, note 281.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid. 694.

[4] Ibid. 900.

[5] David Foster Wallace, The Pale King (New York: Little, Brown, 2011) 143.

[6] Blaise Pascal, Pensées, trans. A.J. Krailsheimer, (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1995), 66; L 201; B 206.

[7] David Foster Wallace, Everything and More: A Compact History of ∞ (New York: Atlas Books, 2003), 107.

[8] Ibid. 22.

[9] Ibid. 22–23.

[10] Ibid. 30.

[11] David Foster Wallace, “Mister Squishy,” in: Oblivion: Stories (New York: Little, Brown, 2004), 5.

[12] Wallace, “Mister Squishy,” 36–37.

[13] Wallace, Infinite Jest, 694.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid. 592.

[16] Ibid. 694.

[17] Ibid. 591.

[18] David Foster Wallace, “Kenyon Commencement Speech,” in: Dave Eggers (ed.), The Best American Nonrequired Reading (Boston-New York: Mariner, 2006), 355–64, at 362–63.