Msgr. Luigi Giussani,

The Risk of Education: Discovering Our Ultimate Destiny

(The Crossroads Publishing Company, 2001; First Italian edition, 1995).

Every time I have the opportunity to speak about education, a concerned parent always asks: “How can I help my son fall in love with Jesus Christ?” Catechetical curriculums aimed to present the Christian tradition via a myriad of activities do not seem to communicate the faith in an appealing way, and they don’t encourage personal commitment. “Why doesn’t he show interest in the faith?” is the common worry of parents.

Monsignor Luigi Giussani had a similar perception while conversing with high school students. Listening and observing his students, he concluded that a clear presentation of tradition was insufficient to generate conviction unless the adolescent is moved to make it his own. To do so, the adolescent must be educated to personally verify the tradition with his experience. Giussani continuously repeated to his students —“I am not here so that you can take my ideas as your own; I’m here to teach you a true method so that you can judge the things I will tell you.” Thus, according to Giussani, the chief concern of a genuine Christian education is to “educate the heart of man, just as God made it.” This approach, he believed, was the only possibility for a faith that can thrive in a world where everything points in the opposite direction of Christianity.

The educator must be an authority on and the concrete living expression of the tradition. He must, that is, have the capacity to “arouse surprise, novelty and respect in the adolescent.” He must be, that is, attractive.

For Giussani, the “heart,” far from being a collection of subjective emotions, is the innate and universal longing for truth, beauty, justice and good, ultimately God. As such the heart is the final standard of judgment. This does not mean, of course, that everyone arrives automatically at the knowledge of God. Because of original sin the heart is “hardened.” To add to the difficulty, Giussani thought that this existential disposition increases exponentially with the influence of the modern mentality so much that it has atrophied the person’s capacity to reason.

In The Risk of Education, the author explores the essential features of a genuine education of the young: tradition, authority, freedom and reason.

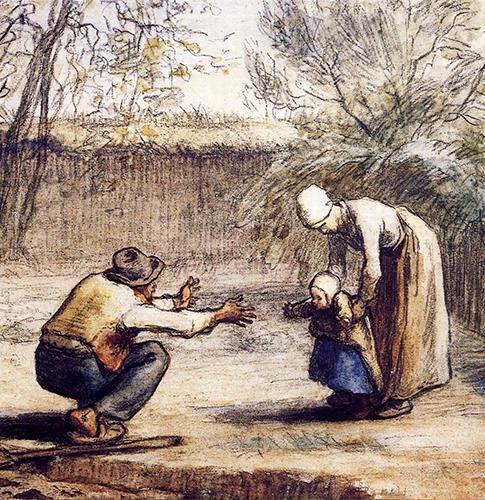

Tradition, for Giussani, is that hypothesis of meaning into which a child is born, and in which the child participates by imitating the parents. Later on, as an adolescent, he must be encouraged to make tradition his own by being taught to “verify” its validity in his personal life. And because Christianity is an event—that must be lived through, not merely read about or discussed—the tradition must be presented as something living, and in the educator himself.

The educator must be an authority on and the concrete living expression of the tradition. He must, that is, have the capacity to “arouse surprise, novelty and respect in the adolescent.” He must be, that is, attractive. In as much as the educator is an authority, he will encourage the adolescent to verify the validity of the hypothesis. In other words, the educator must foster growth.

Tradition and authority, though, do not automatically generate conviction. Ultimately, everything is placed in the fragile hands of freedom. Here lies the risk of education. It is not enough for the adolescent to hear the proposal. He must “prove to himself its value.” Only personal verification can secure conviction.

The Risk of Education is not a how-to book, but an in-depth exploration of the conditions and dimensions necessary to foster the verification of the faith. It provides the basis for the formation of thousands of young people and adults participating in the movement of Communion and Liberation in roughly eighty countries around the world.

Father Medina is a native of Spain and a member of the Priestly Fraternity of the Missionaries of St. Charles Borromeo. He is the national leader of the Catholic ecclesial movement Communion and Liberation.