This title sounds really contradictory. What kind of beauty can there be in a situation near death, especially when babies are involved? And yet, there is some truth to it. With this talk I would like to share my experience of beauty, precisely in situations where it seems impossible to find.

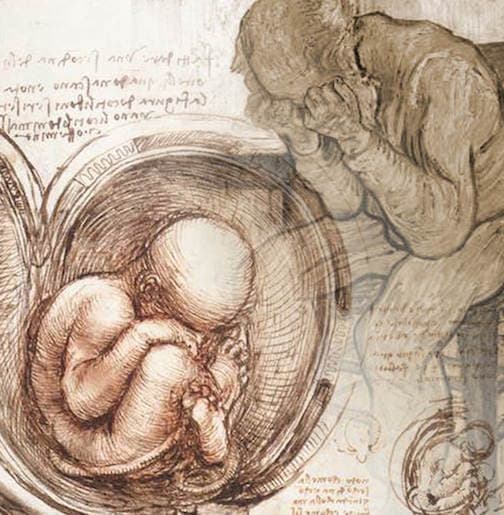

I believe that the moment a baby is born is the time where it is evident that we are made for happiness. What fills me with wonder is entering the delivery room, and there you count the people: a mom, a dad, a nurse, a doctor, a midwife… there you count five persons and, after a while, you count six, for at a certain point there is one more person. It was not there before, and now… there it is. And this little new person arouses surprise, wonder, and enthusiasm in all those around him or her, only and exclusively because he or she is.

The baby does not impose itself because of its physical appearance (blonde or tall or whatever) or because of moral characteristics (coherent or generous), or because of its abilities (intelligent, great in organizing). The baby imposes itself because it simply is. All the surprise and wonder around the new baby are nothing else than the manifestation of hope, an expectation of happiness. I believe that the birth of a baby is not primarily a biological mechanism. It is an event that arouses a limitless promise.

Loving their children is an original need for parents, just as helping the one who asks for help is a primary need for the physician. In that sense termination of pregnancy is not a real medical option.

It is within this context that, during med school, I decided to become a neonatologist. The intuition I had was this: I had this strong desire to support with my medical knowledge this promise of happiness for infants who have medical problems. I wanted to heal these babies and send them home with mom and dad, healthy and happy. In short, I wanted to become a neonatologist because I wanted to save babies.

I work at Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York Presbyterian, associated with Columbia University. We have about seventy beds for neonatal intensive care, and we take care of infants born in our hospital or coming from other hospitals in the state of New York or other states.

The vast majority of infants we take care of go home healthy and happy with their parents. But this is not always possible. There are a few conditions, congenital or associated with prematurity or with other diseases, that are defined as “life-limiting,” that is, they are not susceptible of medical or surgical care. The infants affected with such diseases have a very short life.

For some reason, I found myself at a certain point taking care of these kinds of infants. But how did it happen? It was not my idea, but I was somehow called there by things happening in reality.

In fact, as I said before, I wanted to be a neonatologist to save babies’ lives, and I would never have imagined that I would end up taking care of babies who are not expected to live at all, but supposed to die.

Anyway, in short, this is the story.

Introducing Elvira

As a neonatologist I always loved to be involved in the prenatal care of infants, to give a proposal to parents about the plan of treatment for their babies once they had been born. Unfortunately prenatal diagnosis is more and more focused on the identification of fetal malformation, in order to eliminate infants with any kind of problem. As a physician and a neonatologist I am rather interested in the medical treatment of each one of my little patients, before or after the delivery. I believe that any medical condition can be treated, whether the estimated length of life is ninety years or seven minutes. Therefore, as I had been participating in the meetings for prenatal diagnosis in my hospital, at a certain point I stopped going to these meetings. It was just too painful – the proposal was termination of pregnancy all the time; there was no space for me as neonatologist, and I felt quite useless and impotent.

I had not been attending those meetings for about two years, when, one day, the chief of prenatal diagnosis met me in a corridor and asked me, Elvira, why are you no longer coming to our meetings? They are so good, we learn so many things… and she was sincere. Right there I remember, I told myself, reality is calling me, through the voice of this doctor. Therefore I told myself, okay, I can go back. These babies suffer; I can suffer with them. I can do this.

The following week I went to the weekly meeting and—surprise!—the OB fellow presented the cases of two women expecting babies with Trisomy 18, a life-limiting condition, but these women did not want to terminate the pregnancy. There was a discussion. What do we do now? Who is going to take care of these babies? And so on.… So I raised my hand.

I said, I can take care of them: we can do “comfort care.” To tell the truth, at that moment, I had no idea what “comfort care” meant in any detail, but I said it because I wanted to affirm that there was a way to take care of them. Of one thing I was certain, that I was their doctor, and those babies needed me.

Of course, everybody felt relieved by my proposal. Little by little, over the next weeks or months, they started referring to me all the moms who either did not want to abort their babies or those who maybe would have aborted, but the pregnancy was too advanced.

Before entering into the specifics of comfort care, I want to share with you a very important step in my knowledge of what it means to be a physician, because exactly this point was what helped me in developing the comfort care program. As I said in the beginning, I became a neonatologist to save babies’ lives. But, here I was faced with a question, dealing with these babies whose life is so short. What does it mean to save a life?

It means I cannot give up my desire to save each one of them.

Learning from Reality

In my quite long career, I have learned practically everything from my patients. Therefore I would like to tell you the story of a little baby, Maria Ximena. By taking care of her, I made the following step; that is, I really understood what it means to be a physician, and what it means to save the life of my patients in any condition.

Maria Ximena was born very premature and very sick, in my hospital. During her resuscitation, it was quite dramatic because she is not just one of my patients, she is also the daughter of some good friends of mine. And so I tried all kinds of life support, modes of ventilation—everything—to save her life.

In those dramatic moments I realized that all my medical knowledge, my experience, my expertise, nothing of all this would have kept her alive unless the One who gives her life decided that it should. That is, during her resuscitation, I suddenly understood that while I had to give all of myself, with all my professional knowledge, her life remained in the hands of Another.

In those six hours, without leaving her bedside even for a minute, I understood: to be a physician means using all the expertise, medical knowledge, experience in order to serve the Other who gives life to the patient. And how does this Other let me know about his plan for my patient? Very simply. Through the patient himself. For this reason I am called to be extremely attentive to the clinical signs of my patient, and also to be affectively or emotionally involved in order to perceive any small sign that might lead me toward an appropriate treatment. This experience became fundamental to my understanding of my profession as physician.

In fact, going back to comfort care, this little girl’s story clarified what it means to save the life of my patients, even in cases when life is really very short. It is the same thing. When patients’ lives are very limited in length, I also need to be very attentive and affectively involved in order to perceive which direction their life is taking, and to serve the One who gives life to them and decides how long or how short it is—whether months, weeks, days, or just a few minutes.

Since that day in 2006, when I raised my hand proposing comfort care for those two babies, I developed a methodology to define the Comfort Care Treatment, by following this point exactly. Comfort care is not a matter of “trying to be kind to the patient, and not doing anything medical because there is nothing we can do.” It is not true at all that there is nothing we can do; rather, taking care of these patients is sometimes more complicated and time-consuming than with others. With these patients we need to override policies and guidelines. We need to be creative, using all our medical knowledge and our humanity.

By the way, comfort care should be part of the treatment of any patient, because each patient wants to feel comfortable. The difference is that, in these cases, because there is no recovery possible, the patient’s comfort becomes the main goal of the treatment.

Comfort care management can include medical treatment and surgical procedures, with the goal of making the patient comfortable. I will give you an example. A couple of years ago we took care of a little girl, born with very severe anomalies of her head and face, and the only intact part of her face was her mouth. She was struggling to breathe and feed. She felt suffocated while attempting to eat. Therefore, with the support of her parents, we inserted a gastric tube, enabling her to breathe comfortably with her mouth, and to be fed via her G-tube. She lived four months, and in those four months she was really comfortable.

So then what is comfort care? It is both a medical and a nursing treatment. The principles of comfort care include the satisfaction of some basic needs, so that in order to be comfortable a newborn needs to be welcomed, and to be kept clean and warm. He or she should not be thirsty or hungry, and should not suffer pain.

Therefore, we do medical rounds on these patients and, as we go around, we ask the nursing and medical team, how can we help this baby to be comfortable? This list of needs to be fulfilled seems nothing, too simple; however, this is not the case, because it requires the overriding of policies, rules, and schemes in the neonatal intensive care or in the nursery. And you will see this as I am going through some details.

In fact over the course of the past few years I have taken care of more than a hundred newborns and their families. I lived with them beautiful stories, which also helped me understand many things from a medical point of view. Moreover, I could see so clearly the victory of beauty and truth over limits, lies, and death. I saved a lot of pictures given to me by parents. The predominant feeling portrayed in these pictures is always the joy, the joy to have your child with you now.

I would like to share a few of these stories.

Competing in Love

A few years ago I met an American family, which had been for years on mission in Brazil. Their third baby was diagnosed with a lot of problems before birth, and so they moved back to the US to provide adequate care for this baby once she was born. I met them in my hospital at the beginning of the third trimester, just after the baby had been diagnosed with a life-limiting disease. They told me: Doctor, we will carry our baby as she is, and the most important thing, after she is born, is that we would like to spend the most possible time with her. I explained to them comfort care treatment and, yes, I assured them that they would be able to spend time with their baby in our unit.

I was expecting to see them in a couple of months, at the term of pregnancy. However, after a couple of weeks, I was on call at night and I was called to the emergency room. They told me that a woman had just delivered a premature baby, and this baby seemed to have a very serious disease. I went there and recognized them. I could not believe that it happened exactly the night I was on call. They were happy, too, that I was around.

The little baby was indeed little, a girl of about two pounds, but she was alive and quite active. Because she was so tiny I was worried that she might get cold, but I did not want to place her in an incubator, because this would not enable the parents to stay with her. So I proposed kangaroo care: skin-to-skin contact. Mom and dad alternated in holding her on their chest for the twelve hours of her life. Grandparents came with the other siblings, and those twelve hours were a big celebration! I can say that, together with sorrow, the prevalent feeling was one of joy, the joy of having your baby with you now.

In fact, when I went to greet them at discharge, after the baby had passed, I told them something like, I am sorry for your baby. They told me, Doctor, don’t say, I am sorry, we were happy—yes, they used the word happy—to stay with our baby for those twelve hours. And we are very grateful that you allowed us to spend those hours with our daughter.

Another important need a baby has is to be fed and nourished. These babies are often quite sick, so occasionally they can be fed at the breast or with a bottle, but often they have no strength to suck, therefore we give them some milk with a little syringe, or by placing a little tube in their stomach.

I took care of a little baby boy, the second of twins, who was born with a very severe cardiac condition that could not be operated on. He lived a beautiful life of fifteen days. He was kangarooed and fed with a syringe by mom and dad. When I met the parents during pregnancy I offered them, not options, but my proposal. I proposed myself as the doctor of their baby, saying something like this: I am a neonatologist and I am here to take care of your baby. If medical treatment is not going to be good enough to save the life of your baby, we will make his or her life the most beautiful possible. I believe that any other proposal is not adequate; it does not address the patient and the parents’ ultimate needs, which is to be able to love their baby. And it does not address the need of the physician as well, because as physicians, we need to care for our patients and not just eliminate the problem.

So, when I talk to parents, even before telling them what is going on with their baby, I ask them, is it a boy or a girl? Do you have a name for your baby? By doing so I want to communicate how much I care for their baby, and I see very often what I call an “affective competition.” For a parent it is impossible to tolerate the possibility that there is someone else who loves their baby more than they, therefore my proposal helps them to be free to love their babies.

My proposal is reasonable, based on the fact that we all share the same heart. Loving their children is an original need for parents, just as helping the one who asks for help is a primary need for the physician. In that sense termination of pregnancy is not a real medical option. It is really true that we all have the same heart. In fact beauty attracts and moves people.

A good example of this is that, within a few years of developing comfort care on my own, one by one several nurses and social workers have asked to assist me in this project. In this way we established the comfort care team, some ten people working with these babies and their families. They are nurses, social workers, a child life specialist, ministers from chaplaincy, etc. They help me taking care of infants during their hospitalization, but also training other nurses and medical personnel in comfort care management.

We set aside a “comfort care room,” a private room in the intensive care unit that allows privacy to parents who want to spend time with their infants suffering from terminal conditions. There is a beautiful rocking crib, a bath-tub for the first bath, and beautiful outfits and blankets that we received as donations.

As I mentioned before, aside from nurses and myself, there are other professionals helping. Child life offers activities for siblings, helping them face the drama that is unfolding in their family. They also are able to reproduce tridimensional casts of the hands or feet of the baby as a way of remembering this little child whose life is so short.

We are well aware of the fact that nothing that we do can fill up the emptiness left by the loss of a child, but all these activities allow us to stay with the parents in these dramatic moments. It is impossible for a parent to face the death of their child alone. So, through all these activities, we very simply stay with them.

Alejandra’s Story

Another interesting point relates to the fact that, as we want to assure comfort to our little patients, we don't want to prolong or shorten the length of that life. There is a risk that comfort care might become a shortcut for euthanasia. Life is given, and the length of life of these children cannot be determined by the parents or by the doctors. And so we work to keep our babies comfortable. Nevertheless, we can have surprises. I would like to tell you a story that is very significant in this sense.

Alejandra’s story could be entitled, “When reality surprises us.” Alejandra was born very small, less than two pounds, and she became sick with a very severe infection that destroyed her intestine completely. Back from the operating room, the surgeon told the family and myself (I was her doctor): There is nothing we can do, let her die. Pull the tube.

The parents were desperate and begged me not to stop life support, at least for some time. I followed their desire, not because I thought she would have recovered, but to make them happy, just for few hours or for a day. Also, I thought, she is premature, and I know that premature infants, even if they are healthy, need a minimum of life support because of the immaturity of their lungs. Therefore I proposed to the parents a modified comfort care treatment which included minimum life support, minimum nutrition, one antibiotic because she had an infection, and morphine around the clock. And we observed her hour by hour, day by day. I was sincerely convinced that her life would be quite short.

However, Alejandra was surrounded by people who loved her very much—first of all her parents, then some nurses very devoted to her, and I put myself on the list as well. All these people observed very attentively each clinical sign, and nothing was taken for granted. Weeks passed by, the wound started healing a little bit, and Alejandra started moving and breathing on her own, until one day—incredibly—I had to tell the parents that I wanted to pull the tube, not because she was dying, but because she was able to breathe on her own.

After a few months, she went home. Now, at five months, her weight went from two to eight pounds. Her intestine was very short, only a few inches, she needed parenteral nutrition through a central venous access, and could only drink a small amount of milk, but she was alive. Currently she is six years old, and she goes to school with her feeding tube for a slow infusion of milk in her still very short intestine. She receives parenteral nutrition a few times a week, with the hope of weaning this artificial nutrition over the next three to four years. But she is a very bright and happy girl.

By taking care of Alejandra, I realized with even more clarity that being a physician means being in dialogue with the Mystery, who talks to us through reality, the reality of our patients.

I like to tell parents, as I discuss with them my plan of care for their baby, that, in order to understand what to do in terms of a medical plan, I need to follow their baby. I tell them, I follow your baby, and your baby will let us know what we need to do medically. It is amazing how the parents are very much at peace with this plan, and they are even proud that their babies are guiding the physician.

Learning from Baby

In this sense, taking care of each patient is always a drama, because I need to follow Another; but, exactly because I follow this Other, there is no right or wrong decision. Of course, I experience powerlessness quite often because, as it was so clear with Alejandra, each patient’s clinical course is a sort of mystery. Now it is very clear what happened to her; now we know. But during those months while she was sick, we did not know what to expect. But this sense of powerlessness is good. It opens a space for the Mystery to come, and each time he comes and clarifies.

In front of these infants with such a short life, a question arises for me every time. Why is their life so short? I feel that this is an ultimate injustice. I really enjoy my life, because life is beautiful. We are free, we can enjoy the beauty of nature, we can love and be loved. They are missing all of this.

This question is always open for me, but I began to understand the answer to it a little bit more by taking care of some of my patients who were Siamese twins. Their teenage parents looked like typical teens, with tattoos and piercings all over. After the diagnosis was made, it was strongly suggested to them that they should terminate the pregnancy, but they refused, saying, “These are our babies.” So they continued the pregnancy. We consulted cardiologists and cardiosurgeons, but, unfortunately, the babies could not be operated on because they shared a single heart with severe anomalies, and they also had to be delivered prematurely because mom had very high blood pressure.

The day of their birth, just before the Caesarean section, I was very sad. In the delivery room, many people were commenting about the fact that this mom was crazy to bring the babies to term. They were saying, “She is going to get a Caesarean section. This wound will mark all her life; she will have possibly problems having other children; she should have terminated the pregnancy.” Also there were some young physicians in training ready with their cameras to take pictures of this “rare case”; and, in the very end, it seemed to me that no one was welcoming these babies.

Finally, they appeared, two beautiful little girls, embracing each other because they have been united by the chest their entire life. The father asks me if he could hold them. Of course, I say. The babies were just gasping a little bit, the heart was beating very slowly, and the father kept reassuring them, “Don't worry, Daddy is here.” I told myself, this boy, a typical teenager, probably gets bad grades at school, but he is a great father!

Suddenly I looked around and what did I see? The atmosphere in the delivery room was completely changed, I saw tears, people embracing this young father; the cameras were no longer around. The people were the same, but completely changed.

What had happened? It was a moment of beauty, because beauty is the splendor of truth and the truth is that these babies are. They are, they exist, and the only possible explanation for their existence is that a Mystery called them to life. This is beauty and truth. And this is witnessed by the fact that everybody changed, everybody was moved. This is another proof of the fact that we all share the same heart, despite our ideologies or preconceptions.

Therefore, going back to my question, why is their life so short? Of one thing I am completely certain: their life is the sign of Another who wanted them, who called them to life, even if it is very short. In the shortness of their life I continue to see a sort of injustice, and this remains a tremendous puzzle. However, I see also the signs of something new, unexpected, beautiful. In their short appearance in that delivery room, for a just few minutes, I saw the victory of beauty and truth over lies and death. The change in those people is the witness of this victory.

In conclusion, I would like to say that my job as neonatologist is to affirm that each one of these babies is not the sum of their chromosomes, whether normal or abnormal. They are not defined by the cultural hegemony of this society that considers them useless or even dangerous. They are a relationship with the Mystery.

How can I say this? Because they are, they exist. The Mystery called them to life. And, by creating them, the mystery opens a great promise for happiness. It is possible to taste this happiness in advance when we look, when we really look at reality in its truth.

Like a mom who embroidered a frame and put it at the bedside of her baby. In the frame you can read, You are loved. This mom looked at her baby, and said the only true thing it is possible to say: You are loved.

This is the beauty that I see, and I have shared it with you.

Elvira Parravicini, MD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at CUMC.

Elvira Parravicini is assistant professor of the Department of Pediatrics at CUMC.