Dietrich von Hildebrand,

In Defense of Purity

(Hildebrand Press, 2017).

Dietrich von Hildebrand,

Humanae Vitae: Sign of Contradiction

(Hildebrand Press, 2018).

Few works are extensively reviewed when they first appear, far fewer on the occasion of their republication. Dietrich von Hildebrand’s In Defense of Purity (1927, 2017) and Humanae vitae: Sign of Contradiction (1968, 2018) are two of those rare books. The seminal influence of Purity on Catholic thought and even on magisterial teaching would justify its ongoing consideration. But it is the potency and evergreen character of both works that truly motivate reviews like the present one.

Formed in the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and the personalism of Max Scheler, Hildebrand converted to Catholicism in 1914 at the age of 24. His early immersion in great works of art and music (his father, Adolf von Hildebrand, was an eminent German sculptor) proved to be a powerful driving force in the development of his life of faith. Not only did this sensitize him to see the infinitely greater beauty of the saints and of Jesus, it also sensitized him to the beauty of the virtues.

After his conversion, he spent nearly a decade immersing himself in the Fathers and Doctors of the Church. He also read widely in the Catholic thought of his day. On the theme of love and marriage he was troubled by the many books that approached purity in terms of prohibitions. So he set out in Purity—just as Karol Wojtyła did several decades later in his Theology of the Body—to develop a positive account of the beauty of purity.

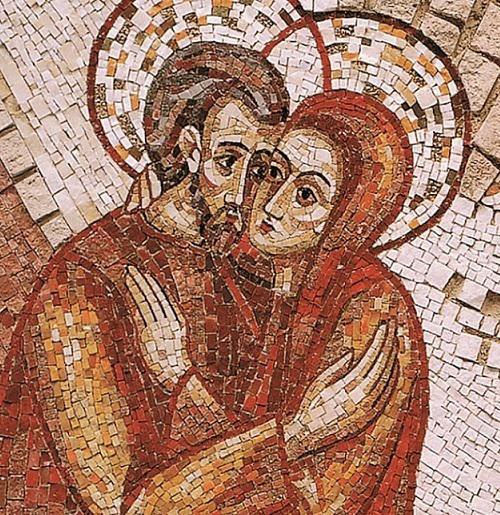

The book is in fact an exploration of purity in married love and in consecrated virginity. This pairing is not accidental, for the inner key to both is the radical gift of self. Purity is a response of love to the mystery of sex, either by enacting the conjugal union or by providing the basis of the special consecration to Christ in consecrated virginity.

Purity marked the start of what became a lifelong meditation for Hildebrand on issues of love, sex, and marriage, including his books Marriage (1929), Man and Woman (1966), Humanae Vitae: A Sign of Contradiction (1968), and The Nature of Love (1971), the latter being the study he considered his most mature philosophical work.

A striking feature of Purity is that Hildebrand lays a foundation for his discussion of purity (and impurity): he begins by reaching back to the personalist fundamentals, exploring the nature of the person, sex, embodiment, affectivity, love, and marriage. This need to “begin anew” surely reflected his dissatisfaction with the scholastic categories with which he was familiar.

Hildebrand begins by looking at sexual experience itself. He finds that sex is distinguished from other bodily experiences, like hunger and thirst, by the fact that it reaches deep into the life of the person. “Every disclosure of sex is the revelation of something intimate and personal,” he says. “It is the initiation of another into our secret.” Sex is thus structurally bound up with the inner life of the person. This explains why sex is linked to shame (in the positive sense of protecting our “mystery”) and why sexual violation (in rape to be sure, but also in lustful marital intercourse) degrades a person in a way that other affronts do not. All of this can only be understood if we approach sex with a particular reverence.

The essential depth, intimacy, and mystery of sex, Hildebrand says, are what give sex its natural orientation to love and self-gift. “We have here to do with an organic unity, deeply rooted in the attributes of wedded love on the one hand, and of the attributes of sex, on the other hand.” This is why he says that any attempt to trivialize sex, using it only for entertainment, inevitably defiles the person.

Hildebrand agrees with the Catholic tradition about the role of the will in sanctioning married love. But his phenomenological commitment to experience leads him to articulate a more explicit appreciation of the role of the heart in forming raw sexual energy into an expression of marital love. “The will by itself can never effect an organic union between sex on the one hand and the heart and mind on the other,” Hildebrand says. “Love alone, as the most fruitful and most intense act, the act which brings the entire spirit into operation, possesses the requisite power to transform thoroughly the entire qualitative texture of an experience.”

A critique sometimes made of personalist thinkers is that they open the door to a person-body dualism by giving such attention to the subjective experience of the person. It is hard to understand how this critique applies to Hildebrand. On the contrary, his entire analysis, beginning with his discovery of the depth dimension of sexual experience, brings to evidence just how deeply person and body are united. This is echoed by the eminent German theologian Leo Cardinal Scheffczyk in his foreword to Purity: “If ever the dualism opposed to the Christian conception of the body has been rebutted and completely dispelled, then it is in this work in which Hildebrand bears eloquent witness to the spiritual character of the body in both marriage and virginity.”

A particularly rich strand in Purity is its rebuttal of the claim that purity is just temperamental sexual “insensibility” (Unsinnlichkeit), that is, the disposition of a “person wholly deaf to the appeal of sex.” Not only does Hildebrand distinguish between a temperament and a virtue, he notes that, “insensibility does not even constitute an environment particularly favorable to the virtue of purity.” This is because purity is an attitude toward sex, so that to be insensitive to it is in a sense to make purity impossible. For Hildebrand, sensibility to sex, even a very powerful one, may permit a much deeper more integrated purity. “The pure man...is the only man who is truly complete. In him a central orientation of human nature is fulfilled.”

Purity also contains Hildebrand’s first articulation of the distinction between the procreative and unitive dimensions of the conjugal act. It is widely thought that Hildebrand was the first to make this distinction; certainly hardly any thinker before Hildebrand made the distinction so thematically. Hildebrand argues powerfully that the personal dimension of love between man and woman is so significant that it must have an intrinsic meaning (union) and not only be characterized by an “instrumental” relation to an end (procreation). In this point too, he is close to Wojtyła who argues the same thing in Love and Responsibility.

Hildebrand returned to the question of the ends of the sexual act in his 1968 defense of Humanae vitae. There he develops the idea of “superabundant finality” to capture the relation between conjugal union and procreation. Hildebrand is struck by the beauty and fittingness that a new person comes to be out of her parents’ conjugal union. The new life is not just instrumentally linked to the conjugal union, but rather is an overflowing from the inner abundance of spousal love. This inner abundance, says Hildebrand, is why even an infertile conjugal act can have great significance as the embodiment of the spouses’ love.

The centerpiece of his 1968 book is Hildebrand’s critique of artificial birth control. He argues not against the interruption of the natural finality of the sexual act (an argument which he thought tended to eclipse the personal dimension) but from the idea that the sexual sphere is uniquely the province of God, who directly intervenes at every conception with the creation of a new human soul. Thus, actively to block conception when it would have occurred constitutes a profound kind of impiety against God as Creator.

It is easy to imagine that this sort of argumentation will fall on deaf ears today. Who still thinks that sex calls for reverence?

But maybe this is why Purity remains so significant precisely in our grave cultural moment. Hildebrand’s vivid and experiential account of the depth of sex, its relation to the person’s most intimate self, sex as privileged vehicle for self-gift, even his account of sexual defilement through casual sex, perhaps, just perhaps, can break through to those weary and wandering souls who long for more.

John Henry Crosby is founder and president of the Hildebrand Project. He and his wife Robin live in Steubenville, Ohio with their two daughters and son.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Free Love at the Price of Children's Well-being.