Most people describe adoption as an institution that is good and noble, meets a real human need (providing a home for a child who lacks one), and ought to be part of the Christian pro-life response to abortion. Yet, from the perspective of women with unexpected pregnancies, adoption is the “non-option.” Elective abortion far outpaces adoption in these circumstances.

The numbers are staggering. In 2020, there were 3,613,647 live births

and at least 930,160 abortions. By contrast, the number of infants placed for private, domestic adoption that same year was 19,658. The annual ratio of abortions to adoptions is nearly 50:1.[1] The wildly disproportionate number of abortions to adoptions reveals that most women facing an unplanned pregnancy do not consider, much less choose, adoption.

Why are adoptions so rare? Why don’t more women choose adoption, especially over abortion? Despite its broad appeal, the social science literature reveals a bias against the actual choice of adoption, especially when legalized abortion is readily available. While the barriers to promoting adoption are varied and complex, this essay seeks to examine a particular challenge posed by a widespread, faulty anthropology and suggests that Pope John Paul II’s “law of the gift” is a compelling alternative lens through which to view and promote adoption.

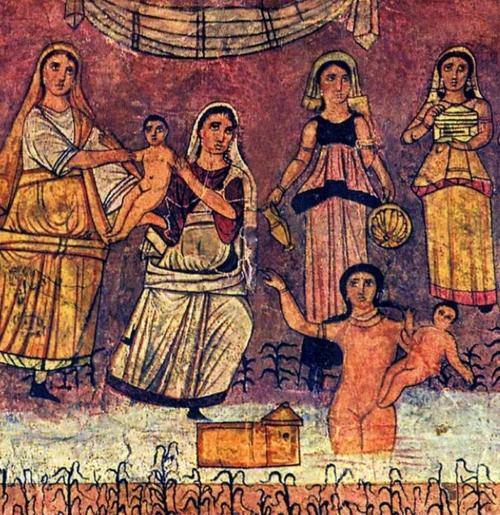

In an address to adoptive families

organized by the Missionaries of Charity, John Paul affirmed, “To adopt a child is a great work of love. When it is done, much is given, but much is also received. It is a true exchange of gifts.” It was fitting that he described adoption so beautifully to families brought together by the Missionaries of Charity[2]

because the care of orphaned children and adoption are at the heart of the sisters’ apostolate.[3] In 1994 at the National Prayer Breakfast, Mother Teresa described the role of adoption in the work of her sisters in this way:

I will tell you something beautiful. We are fighting abortion by adoption—by care of the mother and adoption for her baby. We have saved thousands of lives…. we always have someone tell the mothers in trouble: “Come, we will take care of you, we will get a home for your child.”

This “law of the gift” or “logic of the gift” is often used in Catholic social teaching to describe the generosity of spirit and attentiveness to the common good that should motivate our actions in economic matters, rather than a quid pro quo framework.[4]

Those familiar with the thought of Pope John Paul II will recognize the importance of gift both for the dignity of the human person and its constitutive nature for marriage and the communion of persons.[5]

Man, made in the image of a relational, triune God, finds himself only through a sincere gift of himself.

When standing in the posture of self-gift, a mother’s choice of her child’s good—over and above her own natural desires—is a powerful witness of selfless love to a contemporary egoistic culture.

Motherhood is a paradigmatic example of the “law of the gift,” demonstrating the reality that a pregnant woman is in relationship with, and not antagonistic to, her child. This relationship orients her to the good of her child and thereby to others. As the Pope put it: “This unique contact with the new human being developing within her gives rise to an attitude toward human beings—not only towards her own child, but every human being—which profoundly marks the woman’s personality.”[6]

John Paul’s use of the term “gift” to describe adoption, then, must be understood in this anthropological context of motherhood. Adoption is a great work of love, or a true exchange of gifts, when the adoptive parents and birthparents give freely of themselves to and for one another in love for the good of the child.

What might this “exchange of gifts” look like in the experience of adoption? St. John Paul II says of a mother placing her child for adoption: “much is given.” In a sense, all is given. Placing a child for adoption is likened to experiencing the death of a child. But, unlike in the case of the latter, there is often no public acknowledgement of the pain and loss or adequate resources to support the mother in this difficult time. Yet, in fulfilling her duties to her child as best she is able by protecting her child’s life and future welfare, despite the personal suffering it involves, the birthmother offers a most radical gift of self to and for another. Indeed, in the Scriptural story demonstrating Solomon’s wisdom, it was a mother’s willingness to surrender her child to save her child that revealed her as the true mother (1 Kings 3:16–28).

Social science studies confirm that women who make the rare choice of adoption are those best able to “separate their children in their minds from themselves in order to arrive at a decision about what is best for their children. When birthmothers are able to see their babies as unique persons with their own rights, desires, needs and possibilities, they are better able to determine what is best for them.”[7]

What does a birthmother receive in this “exchange of gifts”? Given the difficult decision adoption involves for her and the natural grief associated with placing a child for adoption, the gift received

by the birthmother may not be easily appreciated. And it may be dependent on the set of circumstances that led her to choose adoption for her child in the first place. We can observe generally that adoption provides the birthmother with the reassurance that her child is loved and provided for, and that she has done what any good parent would do, i.e., to prioritize the good of her child. Over time, such an act, made freely in love, can bear healing fruit.

For example, a birthmother may feel judged or marginalized by others, or have fears related to the adoption decision itself, such as concern over the child’s future reaction to the placement, concern over the child’s well-being, or personal distress at the prospect of separation after the bonding experience of pregnancy. In the face of these natural trepidations, many birthmothers witness to the healing potential of adoption. For example, one birthmother shared, “I loved my child and cared enough about his future to be raised in an environment I could not give him. . . knowing I was actually making a plan gave me comfort in that I could select the family I knew would give my child a good life. It is not a selfish act, but a selfless act indeed.” For a woman in the vulnerable position of an unexpected or difficult pregnancy, who may have been rejected by her parents or the child’s father and who fears the judgment of others, the healing potential of adoption is a gift.

Of course, there are those who regret the decision to place a child for adoption, or whose choice was not voluntary. This phenomenon is especially associated with former practices of adoption that took place in secrecy and shame. In the “baby scoop” era, closed adoptions were the common practice. Then, women facing unexpected pregnancies would temporarily move to another location, have their babies in secret, and return home. The doctor or a child-placing agency would then find an adoptive family, unbeknownst to the birth mother. These practices led to complications in the lives of the adopted child, who was often ignorant of his identity, and also of the mother who had little agency in the process.[8]

This is far different from contemporary adoption practices which are typically open and in which mothers have a great deal of agency. According to one study, “Younger birthmothers felt they had made their decisions voluntarily, and as a result, they ‘owned’ their decisions…. [and feel] empowered and right about it.”[9]

Turning to the adoptive parents’ perspective on the “exchange of gifts,” the most obvious way in which adoption involves a gift is that they receive the gift of a child. Every child is a gift, but adoption expresses this reality in a distinct way because there is no obvious act of co-creation of the child. Consistent with the Church’s teaching on responsible parenthood, adoptive parents—like all parents—ought not to seek to “have” children but instead order their marriage and their home to the welcoming of children. Adoptive parents may be motivated to pursue adoption out of desire for a child, but the end must be oriented toward the good of the child and his parents. Consistent with the spirit of the law of the gift, this outward orientation must be offered selflessly, without preference for their own desires, even if, in the end, the birthmother decides to parent. Adoptive parents must never objectify birthparents as a means to a child. Rather, adoptive parents must be attentive to adoption’s profound potential for the expression of empathy and love to the birthparents—at every stage of the adoption process and thereafter.

What do adoptive parents give? Of course, they do give a home, love, and support to a child. But the choice to welcome a child through adoption is also an expression of the law of the gift. Adoption is a radical gift of oneself for the other, a modern gesture of hospitality to the stranger—not only making space for that person as a guest, but also making a home

for that person as a son or daughter. As Pope St. John Paul II insisted:

Adopting children, regarding and treating them as one’s own children, means recognizing that the relationship between parents and children is not measured only by genetic standards. Procreative love is first and foremost a gift of self. There is a form of “procreation” which occurs through acceptance, concern and devotion. The resulting relationship is so intimate and enduring that it is in no way inferior to one based on a biological connection. [10]

The truth about the human person revealed in the mother-child relationship and as sacrificially lived out by both birthparents and adoptive parents in adoption stands in stark contrast to the individualistic autonomy pursued in contemporary culture and embodied in American law. Many today, whether critics or supporters, view adoption through this distorted lens. Some supporters of adoption view it primarily as a way for adults to have children, especially if they are unable to conceive and bear them. For example, the “godfather” of the legal and intellectual framework of artificial reproductive technologies, the late law professor John A. Robertson, argued for the individual’s right to procreative liberty, not limited to the abortion right of Roe/Casey to avoid parenthood but as a positive “right to form families.”[11]

He proposed that a robust procreative liberty might one day “loop back” to reshape and redefine the way all reproduction is viewed, even so-called “normal” reproduction, and eliminate existing restrictions on practices like baby-selling, leading “to a widespread market in paid conception, pregnancies, and adoptions.”[12]

On the other hand, some condemn adoption as inherently exploitative of women, describing the continuation of a pregnancy only to place the child for adoption as “forced pregnancy” or “coerced surrogacy.”[13] The dissenting justices in Dobbs shared this view, arguing that the availability of adoption does not lessen women’s need for access to abortion because “the reality is that few women denied an abortion will choose adoption. The vast majority will continue to shoulder the costs of childrearing. Whether or not they choose to parent, they will experience the profound loss of autonomy and dignity that coerced pregnancy and birth always impose.”[14]

Similarly, scholars such as Professor Michele Merritt

at Arkansas State University assert that “rhetoric positioning adoption as a reproductive choice or an alternative to abortion is a denial of bodily autonomy.”

Both the Robertson view of adoption as facilitating adults’ desires for children and Professor Merritt’s view that adoption is a denial of the woman’s autonomy share a flawed, individualistic understanding of the human person in which all bonds are actively chosen, delimited, and dissolvable. The choice to place a child for adoption cannot be understood properly, or chosen vis-à-vis abortion, in a culture shaped by such an emphasis on individual autonomy and the exclusive preference of adult desires.

Contra this contemporary view of adoption, the “law of the gift” is based on an authentic anthropology. We are made for communion and self-gift, even sacrificial self-gift; herein lies the path to fulfillment. Distorting cries of “forced pregnancy!” do nothing to alleviate the experiences of vulnerability and obligation that the fact of pregnancy involves, no matter how brief, and only lie to the woman that it is possible to escape such experiences. In contrast, placing the child for adoption is a way for a mother—who, for whatever reason, is unable or unwilling to parent—to fulfill the duties of motherhood in a way that respects her nature and the nature of her child. She is not an isolated, autonomous self with no obligations to others, and her child is not an aggressor. When standing in the posture of self-gift, a mother’s choice of her child’s good—over and above her own natural desires—is a powerful witness of selfless love to a contemporary egoistic culture. Similarly, the adoptive parents’ proper posture of receptivity distinguishes adoption from the pursuit and objectification of children through technologies such as in vitro fertilization and surrogacy.

Of course, all parents ought to prioritize the good of the child due to his inherent dignity, particular vulnerability, and embodiment of the common good.[15]

In those cases where parenting is not possible, the legal institution of adoption is understood to be an exceptional remedy (based on the norm of the conjugal family) to provide a home for a child in need.[16]

American family law is increasingly more vulnerable, however, to Professor Robertson’s “loop back.” The need to answer various questions raised by artificial reproductive technologies—especially the question “who is the parent?”— is giving rise to a re-definition of legal parentage based on intention

rather than on the natural order. In this new imperative, adoption is understood as the form of establishing parenthood rather than the exception, and thereby loses its special character as child-centered. And so, it is perhaps understandable that adoption is increasingly misunderstood as either a vehicle for adults who want children or a means of oppressing women who do not wish to remain pregnant.

The Church, by contrast, understands adoption not as the norm but as a healing remedy, a genuine “exchange of gifts” that respects the nature of mother and child, and an indispensable response to the problem of abortion. Only this kind of radical reordering of our understanding of the human person and of human bonds and obligations will allow us to see adoption rightly as a mode of self-giving ordered not only to the good of the child but also to the parents, natural and adoptive.

[1] The ratio based on reporting in 2020 is 47:1. However, according to Guttmacher methodology, the number of abortions does not include self-managed chemical abortions that are not overseen by clinicians, nor do all states report abortion statistics. Therefore, the number of abortions, and the ratio of abortions to adoptions, is likely much higher.

[2] The Missionaries of Charity were forced to close their adoption services

in India rather than comply with liberalized adoption laws that require children to be made available to single or divorced people.

[3] Indeed, when articulating her reasons for desiring to establish a new order, St. Teresa of Calcutta asked her archbishop to bring the case to the Pope, explaining that the new order would be “especially for the unity and happiness of family life … [we will] give our lives as victims for homes.—By our poverty, labor and zeal we shall enter every home—gather the little children from these unhappy homes.” See Mother Teresa, Come Be My Light: The Private Writings of the “Saint of Calcutta” (New York: Doubleday, 2007), 61.

[4] See, e.g., “Give and take, tit for tat, pay to play — so many of the ‘normal’ ways of dealing with things don’t apply when it comes to children. No one deserves to be born and no parent deserves a child. Life is pure gift; it speaks to us of God, who is pure generosity, pure self-giving.” Francis Cardinal George, O.M.I., “The Cardinal’s Column,” Catholic New World, (October 11, 2009).

[5] See, e.g., John Paul II, General Audience (January 16, 1980): “[The human body] includes right from the beginning the nuptial attribute, that is, the capacity of expressing love, that love in which the person becomes a gift and—by means of this gift—fulfills the meaning of his being and existence.”

[6] John Paul II, Mulieris dignitatem, Apostolic Letter on the Dignity and the Vocation of Women (August 15, 1988), 18.

[7] Charles T. Kenny, “Birthmother, Good Mother,” Family Research Council and National Council for Adoption, 15 (2007).

[8] See e.g., The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades Before Roe v. Wade (Penguin Publishing Group, 2007).

[9] “Birthmother, Good Mother,” 3–4.

[10] See also John Paul II, Familiaris consortio

(November 22, 1981), 28: “However, the fruitfulness of conjugal love is not restricted solely to the procreation of children, even understood in its specifically human dimension: it is enlarged and enriched by all those fruits of moral, spiritual and supernatural life which the father and mother are called to hand on to their children, and through the children to the Church and to the world.”

[11] John A. Robertson, Children of Choice: Freedom and the New Reproductive Technologies

(Princeton UP, 1994), 143. See also Right to Build Families Act of 2022, 117th Cong., 2nd Reg. Sess. (2022) (creating a statutory right to assisted reproductive technology).

[12] Children of Choice, 143.

[13] See, e.g., “The Danger of Forced Pregnancy,” Laura Briggs, Bill of Health.

[14] Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 142 S. Ct. 2228, 2339 (2022) (emphasis added).

[15] See John Paul II, Letter to Families (February 2, 1994), 11: “In the newborn child is realized the common good of the family. … Man is a common good: a common good of the family and of humanity, of individual groups and of different communities.”

[16] See John Paul II, Address to Adoptive Families (September 5, 2000): when the bond of parent and child is “juridically protected, as it is in adoption, in a family united by the stable bond of marriage, it assures the child that peaceful atmosphere and that paternal and maternal love which he needs for his full human development.”