The short story “Leaf by Niggle” is J.R.R. Tolkien’s most sustained autobiographical work reflecting on his relationship with his art. It provides unique insight into how Tolkien conceived of the proper relation between one’s “creations” and the rest of one’s life. The story portrays an artist named Niggle, a painter whose main flaws are his kind heart, which makes him “uncomfortable” in front of other people’s problems, and his perfectionism, which leaves him consistently dissatisfied with his own work. Niggle’s paintings exhibit a particular love for details, one reason why he is never able to finish a project, but which also speaks of his attention to and preoccupation with the reality of things: “He was the sort of painter who can paint leaves better than trees. He used to spend a long time on a single leaf, trying to catch its shape, and its sheen, and the glistening of dew-drops on its edges. Yet he wanted to paint a whole tree, with all of its leaves in the same style, and all of them different.”

Niggle spends much of his life in the tension between the demands of his circumstances—chiefly in the form of his pesky neighbor, Parish, who is always in need of something and has no appreciation for art—and the drive to complete his life’s work, his magnum opus, a painting of a great tree. Niggle is constantly taken away from his work by Parish’s demands, which to him often seem petty and exaggerated. At the same time, the reader is informed that there is a “great journey” looming on the horizon for Niggle, and he is under pressure to finish before the car comes for him, with the implication being that this will be a journey from which Niggle will not return.

The first realm in which we exercise our creativity is in the sphere of our everyday lives, in our relationships with family, friends, and coworkers with whom we daily engage.

In the end, Niggle takes ill from an outing undertaken for Parish, and before he knows it, his “driver” arrives to take him on his final journey. Because Niggle had never packed or prepared for this journey, he is brought to a poorhouse rather than some other, more desirable destination. After a period of rest, care, and simple, monotonous manual labor, he undergoes a “judgment” where two voices weigh his “case” from opposing perspectives. In the end, the gentle voice “wins” and passes a merciful judgment on Niggle’s life on account of that final, wet bike ride that he took for Parish, which he accepted with full knowledge of the cost. What looks like a pathetic failure from the point of view of Niggle’s task and vocation is shown by Tolkien to be in fact the moment of Niggle’s sanctification, leading him to experience the fulfillment of his dreams and desires. For after being judged according to this final act of kindness, Niggle is freed from the workhouse and is deposited inside nothing less than the great landscape of his painting—but brought to life, living and breathing as he had only imagined it:

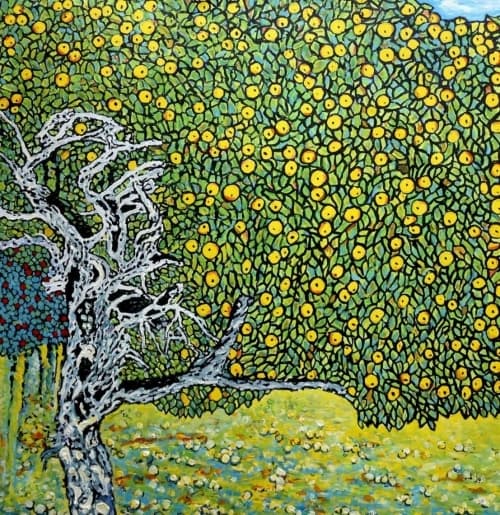

Before him stood the Tree, his Tree, finished. If you could say that of a Tree that was

alive, its leaves opening, its branches growing and bending in the wind that Niggle had so often felt or guessed, and had so often failed to catch . . . All the leaves he had ever labored at were there, as he had imagined them rather than as he had made them; and there were others that had only budded in his mind, and many that might have budded, if only he had had the time.

This landscape is simultaneously the direct fruit of his thought and work, and yet utterly other, more than he could have ever conceived on his own. His response reveals this gratuity: “He gazed at the Tree, and slowly he lifted his arms and opened them wide. ‘It’s a gift!’ he said. He was referring to his art, and also to the result; but he was using the word quite literally.”

The most overarching theme throughout the story is this interplay between Niggle’s dedication to his work and the gratuity with which it is brought to completion in a way almost independent of his direct effort, or at least beyond it. Most of Niggle’s inspirations come in the midst of his being distracted while carrying out tasks for Parish, not in front of his canvas: “Now he was out of the shed, he saw exactly the way in which to treat that shining spray which framed the distant vision of the mountain. But he had a sinking feeling in his heart, a sort of fear that he would never now get a chance to try it out.” Ironically, and despite all external appearances, it is in fact Niggle’s faithfulness to the demands of his life that serves as the deepest source of his work. This becomes explicit at the climax of the story. While looking at his completed tree, Niggle recognizes in each of its leaves the particular moments in which they came into being in his thought, “dated as clear as a calendar.” He suddenly sees that, “[s]ome of the most beautiful—and the most characteristic, the most perfect examples of the Niggle style—were seen to have been produced in collaboration with Mr. Parish: there was no other way of putting it.” For the first time, Niggle realizes that the needs of Mr. Parish and his own artistic creation were never two separate realms with no relation to one another. They had in fact belonged to and impacted each other from the beginning. Unbeknownst to him, even his begrudged acts of self-sacrifice for Parish were in fact the real source of the fruit of his art. The completion of his work, which is now a living thing, required the combined efforts of Parish the gardener and Niggle the painter to bring it to completion. Thus, the two dimensions of “life” and “art” come together, and Niggle is given the chance to complete his work in the fullest and truest way: in communion with his neighbor. The landscape they bring to completion together becomes a haven of peace and healing for further travelers after them, and forever bears both of their names as “Niggle’s Parish.” There is thus finally no opposition between the fulfillment of life and the fulfillment of one’s work, or between Niggle’s imaginative creativity and the reality he is working on.

Tolkien himself described “Leaf by Niggle” as a reflection on his own work. He wrote it during the war after waking up with the idea for the story in his head, during a period of dryness and dead ends in his work on The Lord of the Rings. He had begun to feel, like Niggle, that the project had grown far beyond him and that it would never be done. It is striking to hear Tolkien describe the completion of his work years later in a way similar to Niggle’s own experience of gratuity and surprise. In several letters, he reiterates the curious experience that writing, for him, was more of a discovery: “[The stories] arose in my mind as ‘given’ things, and as they came, separately, so too the links grew . . . always I had the sense of recording what was already ‘there,’ somewhere: not of ‘inventing.’” Tolkien had a deep awareness that his own artistic, creative work was not the sole result of his own effort and undertaking: it was, more deeply, the fruit of a gift received and embraced in obedience. This acknowledgment enabled him to see the intrinsic unity between our creativity, the fruits of our labor, and the charity with which we live our lives; that our fidelity to the seemingly burdensome responsibilities and demands of our lives is not removed from but plays a crucial role in the integrity of our art and creations.

In the story of Niggle and Parish, we are given to see along with them the unity of our work and our lives, and thus, learn the affinity between our work and vocation and our neighbor’s need. These two dimensions require an attitude of attentiveness to reality, ourselves, and to the others who are given to us in order to recognize the deeper, richer ways we can accompany each other. And this attentiveness in turn requires a recognition of our need for each other, to stretch beyond our comfort zones, and receive from the gifts of the other. This fidelity to the whole and responsibility for the other are dependent on a previous attitude of obedience to the circumstances of one’s life. The first realm in which we exercise our creativity is in the sphere of our everyday lives, in our relationships with family, friends, and coworkers with whom we daily engage. Tolkien insists that our primary task is to allow our words and actions to be works of art that witness to the radiance of creation, ourselves, and the person in front of me: to testify to beauty, love, sacrifice, and faithfulness. To live creatively, to use Tolkien’s words, is to be a vessel of “refracted light” and “effoliate” creation: drawing attention to the evidence for beauty, truth, and goodness in the world. In Niggle’s story, Tolkien beautifully presents to us the idea that only a stance of receptivity and gratitude, one that receives our art, talents, and work as a gift, can, in the end, bear fruit in our lives and the lives of our neighbors.

Siobhán Maloney Latar received her S. T. D. at the John Paul II Institute, writing her dissertation on George MacDonald and is currently teaching at Trinity Schools at Meadowview.