Reading Czesław Miłosz’s poetry can feel a bit surreal these days. Frequent visual echoes of his poems flash by on screens, images of cities turned to rubble, armored vehicles patrolling through wreckage, and refugees fleeing across eastern Europe. Miłosz’s poetry is partly a poetry of witness, work influenced by his first-hand confrontation of Nazi and Communist aggression during and after the Second World War.

History laid an unavoidable mantle of experience on Miłosz, who as a young man endured the wartime horrors of Nazi-occupied Warsaw. He referred to the city as “the most agonizing spot in the whole of terrorized Europe.”[1] After the war, Miłosz served in the Polish diplomatic corps as an attaché in New York, Washington, and Paris, all the while moving in the literary circles of these cities. The increasingly repressive practices of the Soviet-influenced Polish regime, along with his disaffection with its communist ideology, led to his defection in 1951, which came at a deep personal cost. Many left-leaning intellectuals accused Miłosz of abandoning their common cause and ostracized him from their circles. At the same time, those on the other side of the ideological spectrum viewed him with suspicion due to his former ties with the Polish state. Biographer Cynthia Haven describes Miłosz hidden in a clandestine French safehouse, separated from his wife and sons, and living in an abandoned and somewhat desperate state. He spent much of this time madly pacing the boards of a small room, chain-smoking, and ruminating on what would later become his landmark prose work, The Captive Mind, a book of essays reflecting on the experience of the artist within a totalitarian state.

Miłosz was eventually reunited with his family and emigrated to California after accepting a teaching position at the University of Berkeley in 1960. He lived most of his life in the U.S. as an expatriate poet, professor, essayist, and translator, before returning to Poland in the years prior to his death in 2004. Miłosz was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980, an award which raised his profile both among English-speakers and within Poland. It was his newfound recognition that enabled him to visit Poland in 1981, making the first public appearance in the country of his native tongue for thirty years. He was a source of hope and cultural resistance for many, inspiring Poles as prominent as Lech Wałęsa and Pope John Paul II. Although Miłosz played down his ties to John Paul II, he and the Polish Pontiff met and corresponded on various occasions, often with reference to Miłosz’s poetry. Once Pope John Paul II spoke with Miłosz with reference to his poem “Six Lectures in Verse,” an extended series of poem-lectures that expressed, among many themes, both a sense of consolation and ambiguity regarding Christianity:

“Well,” the pope concluded, “you make one step forward, one step back.” The poet replied, “Holy Father, how in the twentieth century can one write religious poetry differently?” And the pope smiled.[2]

One can only guess at the source of the smile, but despite the Pontiff’s critique, his fellow-feeling was perhaps found in a sense of kinship with Miłosz. He, too, as a Polish poet, knew the artistic challenge of capturing in words the human longing for God in the midst of the twentieth century’s rubble.

Like a high diver plunging gracefully into a pool, Miłosz’s poetry slices into the depths of a thing, whether it be the face of a woman, the blurred wings of a hummingbird, a sunny terrace overlooking a fishing port, or the torn page of a book, scattered loose with so many others, like dead leaves on the floor of a destroyed Warsaw library. His work pushes against nihilism by discerning a fragile goodness within the world and its things, discoverable only to the attentive eye.

As John Paul II noted, Miłosz’s poetry is multidirectional. He was willing to put a finger on brokenness, but carefully avoided being consumed by it. He eschewed writing poems that were merely “an angry reaction to the inhumanity of our times.”[3] His poems name evil for what it is, either evil writ large during wartime, as in the “buried bodies” and “human ashes” of the poem “A Poor Christian Looks at the Ghetto,” or evil more subtly expressed in the humdrum mediocrity of all those who have lost their sense of the supernatural, as with the people in his poem “Six Lectures in Verse,” whom he describes as having “lost the up, the down, the right, the left, heavens, abysses, / and somehow try to muddle on.” Miłosz strove throughout his life to write poetry that intensely focused on the nuances of reality. With attention to the world as it was unfolding around him, Miłosz captured both its grit and glory. In A Book of Luminous Things, a 1996 edited collection of international poetry, Miłosz celebrated poetry’s ability to attend to the world in all its great variety:

Since poetry deals with the singular, not the general, it cannot—if it is good poetry—look at the things of this earth other than as colorful, variegated, and exciting, and so, it cannot reduce life, with all its pain, horror, suffering, and ecstasy, to a unified tonality of boredom or complaint. By necessity poetry is therefore on the side of being and against nothingness.

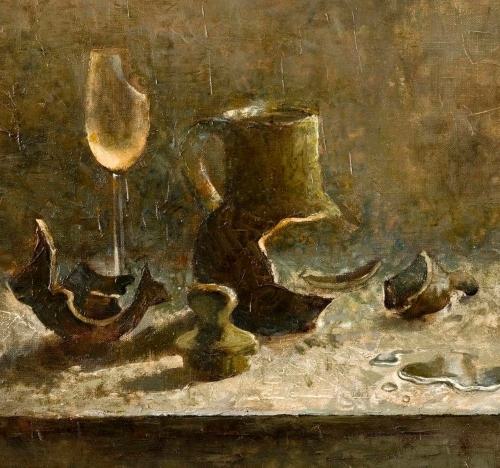

Perhaps it was this fidelity to being, this reverence for the reality of things as they simply are, that enabled Miłosz to avoid producing art mired in anger. He attributed this interest in being to his family’s religious tradition: “My Catholic upbringing implanted in me a respect for all things visible, connected by the property of being, or esse, that calls for unceasing admiration.”[4] This admiration took form in writing that reflects a sense of wonder at being, at an existence given to the world and its creatures via the gratuitous act of creation ex nihilo. Miłosz wonders at the esse proper to both the natural and artificial, at both what arises from the world of nature and that produced by human sub-creators, whose creation is expressed in and through the dynamics of their imago dei. His poetry is steeped in the goodness of the ordinary, which often transcends itself: wine, “sleep[ing] in casks of Rhine oak” reminds a sufferer of the need to age gently into his grief; white tablecloths call to mind the purity of a child’s First Communion; the tin plate and half-peeled lemon of a Dutch painting are so gloriously precise, so solid, that the poet cries out “Rejoice! Give thanks!” Recalling the long-ago heat of a childhood visit to a blacksmith’s shop, the poet writes “I stare and stare. It seems I was called for this: / to glorify things just because they are.”[5]

Miłosz demonstrates a striking ability to articulate how things are luminous, not despite, but because of, their concreteness. He plumbs the beauty of the way particular things share in infinite esse, mining the meaningfulness that shimmers just below the surface. Like a high diver plunging gracefully into a pool, Miłosz’s poetry slices into the depths of a thing, whether it be the face of a woman, the blurred wings of a hummingbird, a sunny terrace overlooking a fishing port, or the torn page of a book, scattered loose with so many others, like dead leaves on the floor of a destroyed Warsaw library. His work pushes against nihilism by discerning a fragile goodness within the world and its things, discoverable only to the attentive eye.

One of Miłosz’s early post-war poems, “Song on Porcelain,” uses a scene of broken tableware to evoke the crushing force of warfare upon an innocent population.

Rose-colored cup and saucer,

Flowery demitasses:

You lie beside the river

Where an armored column passes.

The shattered cups are a “brittle froth,” strewn in black earth that has been churned up by the mechanical violence of war and the digging of graves. The pastoral scenes painted on the cups and saucers are fragmented, an idyll stained by the invading forces of the fallen world. Miłosz’s early poems often reflected upon the tension evoked by these broken saucers: the pull between naming evil for what it is and lingering in the carefree realm of pastoral “festivities” depicted on the plateware. At times he longed to escape to “the greenwood into which Shakespeare / often took me,”[6] where “the wind sways the green leaves gently / And specks of light flick” across the faces of children. Yet these shards, now a “lively pulp” that crunches underfoot, are not the things of a pillaged utopia—they are the vessels of life’s daily rituals, the quotidian liturgies now lost to the scattering forces of war. Like so many people in the wake of conflict, they are displaced, no longer ringing a table in readiness for the morning’s tea or coffee. Scarred, they are tossed upon the recently violated earth. The speaker remarks, perhaps with the derision of a traumatized cynic who has lost the capacity to hold any more grief, that it is all just a pile of “pretty, useless foam.” Yet standing on the disheveled riverbank, the meaning latent within these mundane items cries out to the speaker in a way that is oblique and not-yet-understood; meaning seems to play on the edges of his consciousness, as he muses the refrain: “of all things broken and lost / Porcelain troubles me most.”

The poem, as translated into English by Robert Pinsky and Miłosz himself, echoes loosely the form of a French rondeau, with its repeated refrain appearing at the end of its consistently rhyming 12-line stanzas. The rondeau grew out of a 13th-century musical form that accompanied dancing, featuring the voices of both a soloist and a chorus that repeats the refrain. The poem’s historic ties and the title’s pointed reference to musicality diverge markedly with the subject matter. In the scrabble to survive, who can make time for the “useless foam” of song and dance? The poem’s form stands in defiant contrast to the haphazard wreckage of life it describes. It is the work of a survivor who insists that order and beauty remain, even in the midst of chaos and destruction.

Much later in life, in the years immediately preceding his death, Miłosz wrote an extended poem called “Orpheus and Eurydice.” It lingers in a realm beyond the grave, a crucial space for the aging, expatriate poet, who lamented how modern people had lost the sense of the “second space” of heaven and hell. He noted the loss that attended the “banished metaphysical dimension …[of] Western life, leaving us with a shriveled faculty of imagination, a vision that could not see beyond the little ‘here’ and the little ‘now.’”[7] Miłosz’s use of the classic myth seems to invite his readers to wander imaginatively through questions of the afterlife, meeting with secular moderns in territory less easily dismissed than traditional Christian categories. Written in the wake of personal loss—the death of his second wife—the poem moves beyond eulogizing, into more expansive subject matter. Miłosz stands in the shoes of Orpheus, hunched on the sidewalk of a foggy city street while headlights flash by in the gloom. Beloved Eurydice is lost to the realm of the dead; a figure of both his late wife, and, at the same time, a personalization of the beauty and innocence that the twentieth century saw washed away in a tsunami of warfare, industrialization, and urbanization. The mythological entrance to the netherworld is an urban dystopia: a glass-paneled office building, featuring labyrinthine corridors with robotic dogs whirring past, mechanical stand-ins for the mythical beast-hound Cerberus. As Orpheus descends, he does not enter a place, but a no-place, a “Nowhere,” a “kingdom of no bottom and no end” populated by shades who have “lost the ability to remember.” In hellish contrast with the sensual, nostalgic density of Miłosz’s poems about his childhood, this no-place is “an ashy trace where generations have moldered.” The poet makes his journey to Hades to beg for the release of his lover and for a resurrection of all that has been lost, both personally and culturally, to the “abyss / that buries all of sound in silence.” In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the song of Orpheus is a plea set to music, a lovelorn lament so compelling that the inhabitants of the underworld pause to listen and weep as he makes his case. Miłosz reframes Ovid’s version into a litany of earthly things, a praise of tangibility, of that which is, of esse in all its glorious variety:

He sang of the brightness of mornings and green rivers,

He sang of smoking water in the rose-colored daybreaks,

Of colors: cinnabar, carmine, burnt sienna, blue,

Of the delight of swimming in the sea under marble cliffs,

Of feasting on a terrace above the tumult of a fishing port,

Of the tastes of wine, olive oil, almonds, mustard, salt.

Of the flight of the swallow, the falcon,

Of a dignified flock of pelicans above a bay,

Of the scent of an armful of lilacs in summer rain,

Of his having composed words always against death

And of having made no rhyme in praise of nothingness.

The poetic voice of Orpheus wrangles “against death” with an enumeration of tangible joys, so compelling to his listeners that he wins a second chance for Eurydice. Consonant with the classic myth, however, his mission to rescue her fails due to his own fragility, and she slips away, back to the land of the dead. Has the poet failed in his attempt to name, and thus in some way to rescue the beauty of all that has slipped away in the violent century he witnessed? Perhaps, in his failure, he is simply, as he describes himself in “Meaning,” another late-life poem, “a tireless messenger who runs and runs / Through interstellar fields, through the revolving galaxies, / And calls out, protests, screams.” Yet the poem ends not with a scream, but with solace:

How will I live without you, my consoling one!

But there was a fragrant scent of herbs, the low humming of bees,

And he fell asleep with his cheek on the sun-warmed ground.

Although he has experienced loss upon loss, and the world has been much plundered, consolation remains for Orpheus—and for the reader who rests beside him—in the persistent vitality of the still-undefeated earth: in the green herbs, in the sun that warms the tired body, and in the assiduous bees, adept artisans busy at their task of extracting hidden sweetness.

The poet-figure of Orpheus, face pressed against the warm breast of the world, suggests the intimate position in which Miłosz envisions all poets resting. Only in such attentive vulnerability is the poet able to receive a poem as “a gift from forces unknown.”[8] Yes, Miłosz recognizes that such nearness to the things of one’s own time is a risk. His own life was touched by disaster, disease, and degradation of the widest variety. Yet his poetry serves as a tutorial in how one can distill hope from brokenness, beginning with a reverent gaze upon esse itself:

And so it befell me that after so many attempts at naming the world, I am only able to repeat, harping on one string, the highest, the unique avowal beyond which no power can attain: I am, she is, Shout, blow the trumpets, make thousands-strong marches, leap, rend your clothing, repeating only: is![9]

Carla Galdo is a graduate of the John Paul II Institute, a leader of the national Catholic women’s book group Well-Read Mom, and a student in the Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at the University of St. Thomas-Houston. She lives with her husband, four sons and two daughters in Virginia.

[1] Czesław Miłosz, The Captive Mind.

[2] Quoted in: Cynthia L. Haven, “Czesław Miłosz’ Theological Two-Step,” University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, 30 June 2022.

[3] Czesław Miłosz, “A Footnote, Many Years Later,” in Selected and Last Poems.

[4] Ibid.

[5] From “Mittelbergheim,” “Realism,” and “Blacksmith Shop.”

[6] From “In Warsaw,” and “The World.”

[7] Quoted in: Cynthia L. Haven, “Czesław Milosz’ Theological Two-Step,” University of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal, 30 June 2022.

[8] Miłosz, “A Footnote, Many Years Later.”

[9] From “Esse.”