Season Two, Severance (Apple TV+, 2025).

How far would you go to avoid pain? Would you let someone else die in order not to feel it? Of course you wouldn’t. No one with a half-functioning conscience would say that. But there are other ways we might use others to shield ourselves from what would hurt or cause discomfort. Whole industries are built around it, most recently, the artificial intelligence industry, which saves us from the ultimate discomfort that has afflicted human beings since our creation: having to think.

But there are other more endemic and less controversial industries that have arisen out of a desire to avoid pain and discomfort. Most of us don’t cultivate our own crops or livestock, or make our own clothes or furniture or light sources, or dig our own wells, or construct our own houses. Grocery stores, clothing boutiques, IKEAs, and home construction companies are, in a certain respect, pain-prevention industries. They do uncomfortable things so we don’t have to.

I’m not saying that’s necessarily a bad thing, nor am I saying that we have a moral responsibility to reject these industries. The point I am making is that these industries exist, in part, to minimize our pain, and that this comes at an invisible, though not implicit, human cost. We know it from the data surrounding illegal and aging migrant workers in the farming industry, the “Made in Vietnam” tags on our clothing, the exposés about labor camps producing our Swedish furniture. But we don’t have to see it. That’s the beauty. It’s a bit like the sanitized, clinical, bleach-smelling experience of getting meat from a supermarket. We know there’s blood somewhere, but that’s not important, so long as we don’t see it. What’s important is the meat.

In the Season Two finale of Apple TV+’s Severance, we almost witness a butchering for ourselves, as the psychotic company man Mr. Drummond is moments away from executing the world’s cutest baby goat. The presence of goats on the severed floor of Lumon Industries was one of the show’s enduring mysteries, and in a single scene we learn not only the purpose behind these “Mammalians Nurturable” but also Lumon’s guiding ethos, the rationale behind all their bizarre actions and cultish behavior. The goats serve as sacrifices to the company’s founder, Kier, with this goat intended to guide the soul of the about-to-be-executed Gemma Scout into the afterlife.

As Drummond prepares to shoot the goat, he prays, “we commit this animal to Kier, and his eternal war against pain.” This is the purpose behind severance, the reason for Lumon’s experimentations on Gemma, and the importance behind its “Cold Harbor” project: Lumon is seeking to create a world without pain. This is also why it is so important that Lumon not see its “innies,” its severed employees, as people, which was a danger highlighted by Ms. Huang earlier in the season after Mr. Milchick allowed a memorial service for the just-fired Irving. If innies are persons, then Lumon would be causing more pain rather than preventing it. But if they aren’t, then the severance process provides an unprecedented opportunity in human history, the removal of all pain and discomfort from human life, a total transcendence from pain. The montage of experiments we see inflicted on Gemma—going to the dentist, travelling on turbulent airplanes, writing dozens of thank-you cards for Christmas gifts—are all uncomfortable moments in our lives that we can’t outsource. We can pay someone to grow our food, but we can’t pay someone to go to the dentist for us. The severance process, however, opens up a new commodity market: a fragment of ourselves we can force to suffer on our behalf, someone to whom we can outsource all our pain without having to remember it.

Their great escape is simply another chapter in Kier’s eternal war against pain, a revelation that a dystopia centered around pleasure would be too much effort—better to avoid the hurt now and worry about the consequences later.

For the last six years, I’ve taught freshman undergraduate students Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. For all the discourse that Severance has generated, I’m surprised that more parallels aren’t drawn between the show and this novel. Huxley’s World State takes philosophical materialism to its logical conclusion, depicting what a society would look like if it took seriously the assumption that all that exists is simply material. Under this cosmology, human beings are merely complex chemical processes, possessing no more inherent dignity on an atomic level than any other piece of matter.

This vision of the human person comes with an associated ethic as well, namely, that if all that exists is matter, then human happiness—just as much any sort of human suffering—is merely material and chemical. Workers in the World State are preassigned jobs and social castes from before birth, are taught via subliminal messaging to participate maximally in consumerism, and are paid for their work—most of which is ultimately meaningless and exists only as busywork—in tablets of soma, a drug that produces all the pleasant feelings of the best opioids with none of the side effects, and in money that they can use to purchase elaborate sports equipment and unnecessary new clothing. Sex is “free” and polyamorous; female sterilization and convenient abortion options prevent there from being any consequences to these trysts.

The World State’s religious figure is Henry Ford and, though his adherents do not think he possesses any sort of literal divine power, they do extol him for creating the assembly line method of work that all aspects of their society rely upon. World State citizens regularly participate in mandatory “orgy-porgies,” soma-infused liturgies that mock the Mass and aim to dissolve the individualities of the ceremony’s twelve participants into a “social river” that exists only to serve the needs of the State.

The parallels between the World State and Lumon are obvious. The infamous waffle party from the end of season one closely parallels the orgy-porgy. Ford and Kier are afforded the same level of reverence in these respective ceremonies, though true believers like Harmony Cobel’s family do appear to believe that Kier is some sort of actual deity. Kier, like Ford, developed the underlying process that keeps his “society” going, the reduction of the human person into four “tempers,” which in its final form converts Gemma’s thoughts and memories into numbers on a screen, “macro-data” to be refined. Critically, though the show unambiguously depicts Lumon’s treatment of Gemma as inhuman, the Cold Harbor project and the division of Gemma’s consciousness into twenty-five “innies” are shown to be effective, which means that it really is possible to express the entirety of who a person is mathematically, as bunches of numbers, a positivism if not a materialism.

More importantly, however, is where Brave New World and Severance diverge. Huxley’s dystopia presumed that a society separated from any sort of transcendent ends would ultimately devolve into what Josef Pieper would call a world of total work, in which even pleasure becomes a process. However, the World State, all the way up to its highest controllers, does indeed want its people to be happy, at least according to its own definition, i.e., experience minimal discomfort and maximal pleasure. Where society fails is in not being able to account for the parts of the human person that aren’t reducible to matter, including the unitive and procreative elements of the sexual act which are obliterated by the World State’s approach.

Severance’s dystopia does away with the second half of the World State’s vision of happiness: Lumon and, indeed, most of the show’s characters, seem to define happiness exclusively as the absence of pain. Mark Scout, for instance, begins working for Lumon to forget about the apparent death of his wife. Lumon doesn’t seek to make its workers or customers happy. From the beginning, Lumon’s business is in anesthetics: its original product, ether, to which almost all of Harmony Cobel’s childhood town is now addicted, numbs pain and knocks you out, but it doesn’t produce the same sort of “lunar eternity” high as soma does.

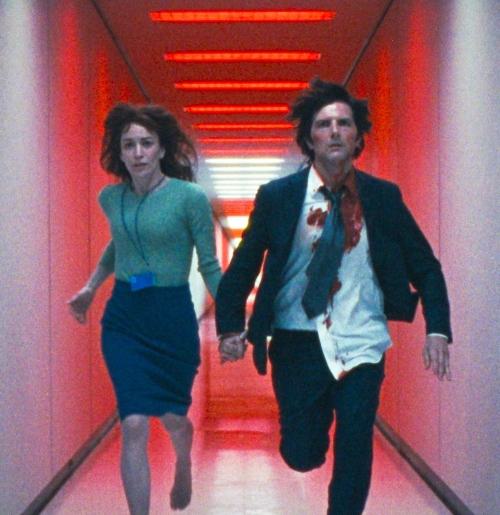

All of these threads converge in the season’s final moments, as Mark’s innie helps Gemma escape the severed floor only to then abandon her and run off (literally) with Helly R., the innie of Lumon heir apparent Helena Eagan. Innie-Mark knows that as soon as Cold Harbor is completed, his life and the lives of all the innies at Lumon are forfeit—the only chance he has at happiness is to trust that his outie will complete the risky reintegration process and live happily with his newly-rescued wife. And yet, with his hands on the crash bar, innie-Mark finds himself unwilling to give up his life, and he finds that Helly agrees. Despite her earlier protestations that Mark should flee from Lumon with Gemma, Helly has pursued Mark to the emergency exit. With Gemma screaming impotently in the background, Mark and Helly run away together into Lumon’s labyrinthine office space, their lives perhaps having only seconds left before being remotely deactivated.

Why does innie-Mark make this decision? For the exact same reason that outie-Mark chose to work at Lumon in the first place: to escape the pain of not being with the woman he loves. Mark’s and Helly’s lives on the run will certainly not be filled with pleasure, but the alternative—not to be with her—is worse. To achieve this, Mark risks everything he and his allies both inside and outside of Lumon have been working for the entire season: when we last see her, Gemma is still in a staircase on a lower floor of a building where people have successfully kept her hidden for over two years, and without outie-Mark to help guide her to safety, there’s no telling what will happen to her next. In the season’s last seconds, Mark S. proves that he’s willing to place the lives of his outie and his outie’s wife at risk so he doesn’t have to feel the pain of Gemma’s absence, and he is willing to let another die to make that happen— in so doing, he has let Lumon win. He has followed Kier. Our confirmation of this comes in the season’s very last shot, before the credits: a still of Mark and Helly running away in the style of the same paintings that decorate Lumon’s halls as propaganda. Their great escape is simply another chapter in Kier’s eternal war against pain, a revelation that a dystopia centered around pleasure would be too much effort—better to avoid the hurt now and worry about the consequences later.

John-Paul Heil is a Core Fellow at Mount St. Mary's University in Emmitsburg, MD. He received his PhD in history from the University of Chicago and his writing has appeared in Time, Smithsonian, and The Week.