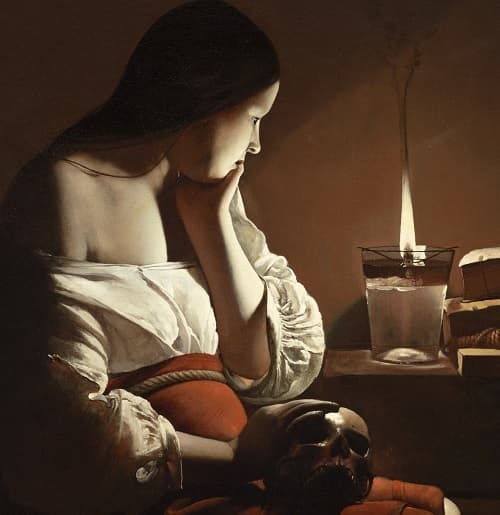

To be embodied is to be vulnerable. Vulnerability strikes us as negative and with good reason, rooted as it is in the word “wound.” But the ability to be wounded is in the first instance the capacity to be affected—moved—by another. To be vulnerable is to be in need of help, in attaining something, in growing up, or just in being. “I am wounded with love,” says the Bride of her Bridegroom (Song of Solomon 2:5). Our bodies open us to the world.

Indeed, it is in the embodied-ness of human beings where this positive vulnerability is most on display. The human infant is at once the most awake to the surrounding world and the least capable of facing it on its own, as compared to other higher mammals who “flee the nest” almost immediately. In her essay, Susan Waldstein introduces us to the prominent biologist, Adolf Portmann, who suggests that the reason for our “premature birth” and need of the “social womb” of the family, is the human being’s greater openness to the world, and his need to be taught about the truth of the world…and the truth about its Maker, as Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche community, reminds us:

This is the glory and the tragedy of humankind. St Augustine’s words, “My heart is restless until it rests in God,” apply to each and every human being. The wounded heart of every child, with its fears and selfishness, comes from an awareness—more or less conscious—of this emptiness deep within our being which we desperately try to fill, but which we find nothing can totally satisfy.

Of course, all of this openness, beginning with the openness to those who introduce us to the world, makes us susceptible to a host of wounds in the more obvious, negative, sense. This issue takes up the full range of that bodily vulnerability, from the kind suffered by the unborn to the that suffered by the dying, even the dead.

Beginning with the “cradle,” Michael Hanby confronts the darker roots of the early contraceptive movement, bringing forward the lesser-known fusion between eugenics and progressive-era Christianity, where prominent Protestant ministers would compete in sermon contests sponsored by the American Eugenics Society which resulted in families “dramatically reducing their family sizes within a generation, anxiously measuring their children by the new standards of ‘scientific parenting,’ and parading their families about like livestock at the county fair in ‘fitter family’ competitions around the country.”

Looking to the life of the unborn, Daniel Moody, author of The Flesh Made Word, argues for a direct link in law between the person-less body in the womb that legalized abortion gave us, and the body-less person outside of it that “gender” is giving us now. Molly Meyer, author of one of the most exciting and beautiful new Theology of the Body curricula for school children, offers a path forward for parents bringing up children, who are now doubly vulnerable amidst this legally sanctioned dis-embodied culture, and who need more than ever to reconnect with the wonder of nature.

Adults are vulnerable too, of course. By virtue of their natural beauty, women are vulnerable in a very specific way to objectification, be it in its “voluntary” or coerced form (human trafficking). Eleanor Gaetan, senior legislative advisor for the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, disabuses us of this fraught distinction in her expert exposé of the lobby that works to normalize and legalize the buying and selling of human beings, rationalizing the denial of human dignity to others with its obsession with sexual libertinism (its ultimate yardstick of personal freedom). Judith Reisman and Mary McAlister, in their turn, offer a comprehensive account of the genealogy of this obsession by way of Alfred Kinsey.

And, for their own want of love, women can inflict violence on themselves, through anorexia, which ultimately feeds on the nihilism of our age by negating all the distinctive weightiness of the feminine body, as theologian Angela Franks says. The award-winning novelist Suzanne Wolfe offers an exquisitely wrought reminiscence of her return to the world of her youth—its goodness and abundance at the family table and the altar of the Lord—after wandering in the wilderness of anorexia, “fasting,” and “nullifying the world.”

And since violence can be suffered by all, men and women alike, we review two books on trauma which show the crucial connection between the body, soul and mind for understanding all trauma, and the special role of the awareness of the body in the work of restoring mental health.

Finally, our bodily vulnerability is most evident in the universal inevitability of sickness, aging, and finally death. Addressing the question of aging, a brilliant emerging bio-ethicist reviews for us Being Mortal, written by surgeon Atul Gawande who, as the son of immigrant parents from India, is caught between two cultures. The one that gave his American in-laws a dis-embedded autonomy and then put them in a sterile nursing home when they finally lost it, and that of his Indian grandparents, who were deeply embedded in a rich network of family relations and activity until the very end. We also review About Bioethics, by Nicholas Tonti-Filippini, a bio-ethicist who, because of his own serious illness, knew first-hand the difficulties faced by those on the brink of death.

Even after death, the body is vulnerable, especially now that we, in the Christian West, are increasingly incinerating what had always been placed in the grave. We began our year with a magnificent article by Patricia Snow on what is at stake in the perennial Christian advice to bury the body. And we end it with a speech on the importance of this,given by American Catholic philanthropist Sean Fieler, who after reading that article, is now working with Snow to promote a return to the Christian practice which, combined with our marriage practices, would offer a more consistent picture of what we think is at stake with the body.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the US editor for Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, The Wound in the Depths of Every Heart.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the editor of Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

Posted on March 19, 2019