Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building (Oxford University Press, 1979).

It is rare for a book on architecture and design to adopt the tone, let alone succeed in expressing the wisdom, of a spiritual classic like the Tao Te Ching (c. 500 BC). I am tempted to see such a book in The Timeless Way of Building, third in a series from Alexander’s Center for Environmental Structure at Berkeley. The leading author of A Pattern Language (1977) which helped shape the New Urbanism, and The Oregon Experiment (1975), which described the implementation of these ideas at the University of Oregon, Alexander is one of the most influential designers of our time, a leader of the reaction against modernist tendencies that tie all design to the material functionality and a reductive attitude to the human person.

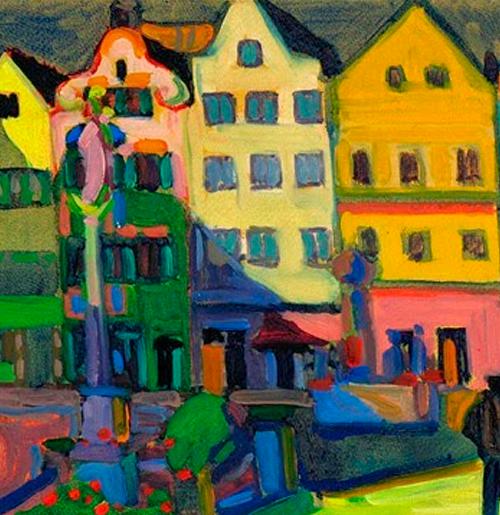

He sums up the philosophy of this book as follows. “There is one timeless way of building. It is thousands of years old, and the same today as it has always been. The great traditional buildings of the past, the villages and tents and temples in which man feels at home, have always been made by people who were very close to the center in this way. And as you will see, this way will lead anyone who looks for it to buildings which are themselves as ancient in their form as the trees and hills, and as our faces are.” So, you see, the “timelessness” he has in mind is not an abstraction from time and history, as with modernism, but a settling right down into history and the bodily existence of the person (especially the “face”).

The book is designed in keeping with these principles. It begins with the whole, not the part, and seeks a balance between complexity and simplicity in which Alexander sees the key to “life” – not merely biological life, but life in general, which he also calls the “quality without a name” and describes poetically as “a self-maintaining fire.” The book is divided into three big, simple parts and then under brief paragraph headings that summarize the main principles and insights. You can read no more than that, he says, and still get the gist of his approach. In between these italic paragraphs, though, the designer or architect will find much guidance and inspiration.

Doorways, windows, halls, living rooms – and public spaces such as sidewalks, market squares, parks – according to Alexander, all are governed by certain rules that determine whether they have “life.” Does the design of the doorway, for example, reflect a real transition between states characterized by a qualitative difference? Does it enable us to appreciate a movement taking place into or from the interior, with the changes that implies for the one who moves between the two? Dozens of such elements of our built environment are listed and explored in the earlier volume of the book series called A Pattern Language, in which Alexander and his colleagues develop in great detail the pattern language that applies to each of them. So equipped, the designer should be able to build anything from a college to a shed, from a harbor to a museum, from an intimate courtyard to a neighborhood, in a form that will delight the spirit and survive the centuries.

It’s not just that the success of the various elements and features depends on how useful they are to us. Alexander is concerned to show that the quality without a name is “objective” not merely subjective. It belongs to a bigger context, in which we certainly play a part, but not the only one. The underlying philosophy of this approach is one that overcomes a false dualism between subject and object, interior and exterior. The two belong to a unity, and imply each other. The risk is always that of falling into a kind of monism or pantheism, but Alexander ultimately avoids this.

Furthermore, the point of the Timeless Way volume is to show how the designer must transcend Pattern Language altogether. The rules of language and structure, of spontaneous organic growth, of algorithmic processes that operate unconsciously, of emergent order, would seem to enable a designer to create environments that are full of life, but of course the “language, and the processes which stem from it, merely release the fundamental order which is native to us.” The language will only “work” of we forget both it and ourselves, attaining a kind of “innocence” in the act of designing which is completely open to what will happen next. The language is far from useless, therefore. It is the pattern language that “frees you to be yourself, because it gives you permission to do what is natural, and shows you your innermost feelings about building while the world is trying to suppress them” (p. 544).

Stratford Caldecott MA (Oxon.), STD (hc), the founding Editor of Humanum, was a graduate of Oxford University, where he was a research fellow at St Benet's Hall. A member of the editorial boards of the international Catholic review Communio, The Chesterton Review, Magnificat (UK), and Second Spring, he is the author of several books including Beauty for Truth's Sake, Beauty in the Word, and The Radiance of Being.

Posted on July 24, 2014