In Memoriam: Stratford Caldecott (1953-2014)

Health: Issue One

It is with great sadness that we note the passing of this journal’s Founding Editor, Stratford Caldecott, who died last month in Oxford, England after a three-year struggle with cancer. We shall remember him, not only as one of the most brilliant and original Catholic thinkers of our time, but also as one of the great contemporary champions of what John Paul II called the “culture of life.”

Stratford was possessed of an extraordinarily versatile mind, which he applied with supple mastery to a vast range of topics that included--to take just a few examples at random--the theological implications of quantum mechanics and the spirituality of Tolkien, Islamic-Christian dialogue and the nature of economic rationality. Yet no matter how far afield he might range, his intellectual exploration was always guided by the same attitude of childlike wonder at God’s inexhaustibly surprising gifts. This wonderment never degenerated into sentimental effusion, however, but found constant expression in a plain, candid, and robust lucidity informed by a gently self-deprecating humor. Stratford’s style as a thinker was a model of sobria ebrietas that perfectly matched the central intuition around which his thought took shape--the intuition that the most realistic approach to the world is to welcome it as a gift “coming down from the Father of lights” (cf. Jas 1:17) who has fully revealed himself as love in Christ’s voluntary self-gift on the Cross.

Stratford’s capacity for wonder flowed naturally into an uncommon intellectual empathy. He had a rare talent for seeing things from other points of view, and he was always anxious to do justice to the objections and questions posed by his interlocutors. A passionate seeker of truth who loved and respected the same passion in others, Stratford was always prepared to acknowledge “seeds of the Word” wherever he might find them. At the same time, he never made a secret of his rich Catholic faith, or hid his conviction that Christ alone is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Rather than regarding dialogue and evangelization as mutually exclusive activities, he understood them to be inseparable expressions of the same encompassing confidence in divine generosity: To seek the truth with his interlocutors was to be on the way to Christ, just as to know Christ was to do justice to the (partial) truth they had recognized. In this sense, Stratford’s work is a timely witness to the truth that, “in revealing the mystery of the Father and his love, Christ, the New Adam, revealed man to himself and manifested his most high calling” (Gaudium et Spes, 22).

Stratford’s remarkable intellectual generosity lifted him beyond the sterile either-or between “Right” and “Left,” “liberal” and “conservative” in the Church. Although he faithfully embraced the whole of Catholic teaching, he never trumpeted his own orthodoxy or abused it as a pretext for self-assertion. Indeed, his entire work was informed by the conviction that Catholic truth cannot be the jealously guarded possession of a party, much less of any self-anointed elect, but is a universal good that illuminates the entire human condition. It was only logical, then, that, in defending the Church’s teaching about the good of human life, he should seek to situate it within the larger web of truths--truths about God, the natural world, and the just society--from which it remains inseparable. It is worth stressing that Stratford’s thinking about these matters--like his thinking in general--was itself part of a larger web, a network of relationships spreading out organically from their natural center: his loving intellectual communion with his wife Léonie and--as his children grew up--with his three daughters as well.

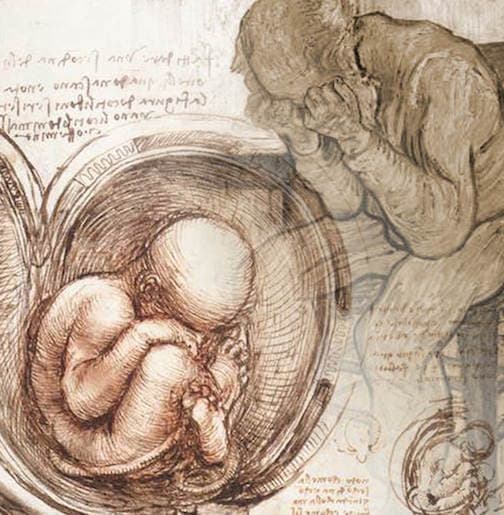

Stratford believed that the fundamental note of reality is not stinginess or calculation, but generosity freely given and freely received. Created being, he felt, is a gift, indeed, a self-giving bestowed by, and imaging, God himself. In the same spirit, he saw the Church’s teaching on the beginning and end of human life not as a collection of arbitrary rules, but as a mystagogical initiation into the sacred vision of triune generosity shining through human birth, reproduction, and death. Stratford’s deepest contribution to the “culture of life,” then, was not simply to produce an impressive array of arguments for magisterial doctrine concerning abortion, contraception, or gay marriage. It was to re-open our weary eyes to the wondering contemplation of the ever-fresh source from which every such argument must derive its power: the radiant generosity of being, itself a revelation of the God who is unreserved generosity in the eternal communion of the Father and the Son in the Holy Spirit.

Adrian Walker is a translator, writer and editor for the International Catholic Review, Communio.

Posted on August 19, 2014