A Brief Introduction to the Issue

Work: Issue Three

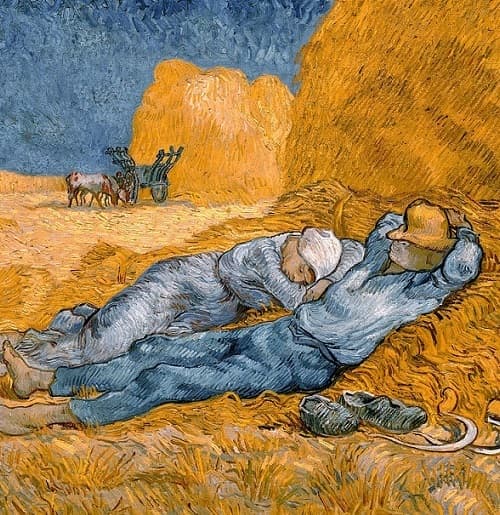

In the third issue of our “work year” we turn to good work and fruitful rest. We are well aware of the degrading characteristic of much of today’s work among the new class of “knowledge workers,” alienated as they are from their bodies and the products of their labor. (We leave the question of backbreaking toil and sub-standard wages to which the less fortunate are subjected to our fourth issue on work and justice.) We are also well aware of how much our “rest” has become passive, lonely entertainment. Here we ask if the question of work and rest don’t stand and fall together. If rest were real rest, what would that do for work? And how would good work open us up to more fruitful rest?

Looking at rest, Saint John Paul II’s re-introduction to the “Lord’s Day” (Dies Domini) is as timely as ever for us who can no longer remember a week without the week-end, but who may have lost the memory of true rest. To rest with the Lord, says the late saint, is to participate in His enjoyment of “what has already been achieved”: the end that work attends to. Péguy puts this “Sabbath rest” on display with his inimitable account of the child at play, “wasting time,” doing “useless” things, because she is resting in what has “already been achieved,” what is already given that is, enjoying it, being together with it. Indeed, we see with Cardinal Sarah, that Christian silence does not leave us alone, but puts us in front of a presence (if we would only liberate ourselves from the “dictatorship of noise”). Finally, the Abbot of Clear Creek Abbey, one of the disciples of John Senior (also featured in this issue), tells us how the deep joy of monastic “silence” before God gets expressed among the brothers in times of recreation—on short and long (10-mile!) walks—through conversation, laughter, and above all a smiling face.

What is the relation between rest and work? On this milestone anniversary of the Reformation, David L. Schindler reviews the classic text by Wax Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, focusing especially on the effect of “disenchantment” that came with the separation of the “worldly calling” from the abolished “idle” one (monasticism): the loss of an inherent good, a utilitarian view of work, and a less home-like world. Looking at the question positively, William Hamant considers the direct relation between home and work, so that the entire world may be transformed for the glory of God, but that this transformation only take place when we belong to a place (a home!). As for the positive relation between work and rest (in the rich sense), Erik van Versendaal follows Péguy. Work has to begin with the acknowledgment of something given (“what has already been achieved”). But wary of the disparagement of work, he explores the way in which work adds something to rest. Work, he suggests, expresses the adult effort to endure, to win and embrace what has been given “for free.” Given the current anniversary, the text from St. James comes to mind: “faith without works is dead.” Finally, Deborah Savage brings back us back to our starting point with her essay on work and the Eucharist. It is in the Eucharist that all work finds its end, since there Christ offers Himself to the Father together with “the work of human hands.”

Within this comprehensive arc, we also consider several popular books on the topic of work and rest, one on the problem of distraction (Deep Work) written by Cal Newport, another on the need for rest (Rest), and finally one on the fascinating phenomenon of the return to Old Jobs (barbering, butchering, distilling, and bar-tending) all of which involve real skill, tangible results and social interaction with customers.

With all of this we wish you some fruitful (and restful) reading!

Margaret Harper McCarthy is the US Editor of Humanum

Keep reading! Click here to read our next article, Rediscovering Sundays.

Margaret Harper McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Theology at the John Paul II Institute and the editor of Humanum. She is married and a mother of three.

Posted on November 10, 2017