St. Jerome Curriculum Group,

The Educational Plan of St. Jerome Classical School

(2010. Available at http://www.stjeromes.org/stjeromeschool/classical_...).

After a few years’ steady use of the internet, journalist Nicholas Carr began to worry about his “inability to pay attention to one thing for more than a couple of minutes.” In his bestselling exposé, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to our Brains (2010), Carr pinned the blame for his wandering mind squarely on technology. This is only the most recent warning on the subject. Two decades ago psychologist Edward S. Reed judged that “we are allowing our mental resources to erode,” and he wrote before the internet became either a household tool or a hand-held preoccupation (see Reed’s The Necessity of Experience, Yale, 1996).

It would seem difficult to deny that ours is now a culture of distraction, and so it is inspiring to see a grammar school squarely confront the challenge of the smart phone, and indeed throw down the gauntlet before it. “Real education,” write the authors of The Educational Plan of St. Jerome Classical School, “requires a space where children can experience a measure of freedom from these technologies and develop independently of them.” Such candor is refreshing, yet what is remarkable about the vision of St. Jerome’s is how it not only opposes our technological distractions but also includes—and arguably at its center—a coherent and principled plan to inculcate the opposing habits of attention.

Billing itself as “a Catholic Classical school in Prince George’s County,” St. Jerome’s Academy is a parochial school, with a kindergarten and grades 1 through 8. The Educational Plan of St. Jerome Classical School is a comprehensive overview of the school’s curriculum. It includes a narrative statement of principles, a discussion of the pedagogical aims of each of the main divisions of the curriculum, a thorough catalogue of the objectives or intended learning outcomes of the classes, reading lists for each grade, and, finally, a thoughtful collection of appendices that give additional guidance to parents and teachers about the school’s philosophy and its expectations for daily life, from dress code to liturgy.

It is an adventure in knowing and doing that the students are invited to join, because we are born to learn and to love what we know, and all these disciplines and activities are unto that high end.

Those familiar with the revival of classical education in parochial, charter, and independent schools, as well as the classical or liberal-education part of the homeschooling movement, will here find many recognizable themes, figures, and texts. The study of grammar is prominent—both the English and the Latin—as are those of the other arts of the trivium, rhetoric and logic. Music and mathematics are both pursued with an eye to classical standards of harmony and intelligibility. As is common in the better schools, a sound cultural formation in literature and history is provided. And a renewed catechetical approach to the teaching of the Catholic faith—using the Ignatius Press Faith & Life series—occupies a privileged place in the whole. All of it nourishing fare.

From the curricular point of view, two items stand out in particular. First, at St. Jerome’s Academy experience of nature—and especially of living things—is a major part of the children’s education. They keep nature notebooks in which to record their field work, dissections, and attempts at classification, and are encouraged to revere nature and its intelligibility as gifts from the Creator. Second, the architects of the curriculum have striven to present cultural artifacts that avoid the all-too-common pitfall of the “Great Books” approach, a premature sophistication of texts, problems, and subjects. The reading lists provided for the literature and history classes show that the innocent wonder and delight of the students will not be sacrificed to the desire of parents or teachers to have children hurried along into cultural elitism. That being said, the curriculum does include a Socratic component of open discussion as well as an emphasis on reading aloud, both of which activities are meant to put before the children “great works which seem slightly out of reach” in an effort to help them “discover the wonders of language” and the “power of big ideas.” To my mind, however, the books listed for these activities seem suited to achieve those goals without the collateral damage of encouraging the jaded, ironic snobbery that, sadly, sometimes masquerades as liberal learning today.

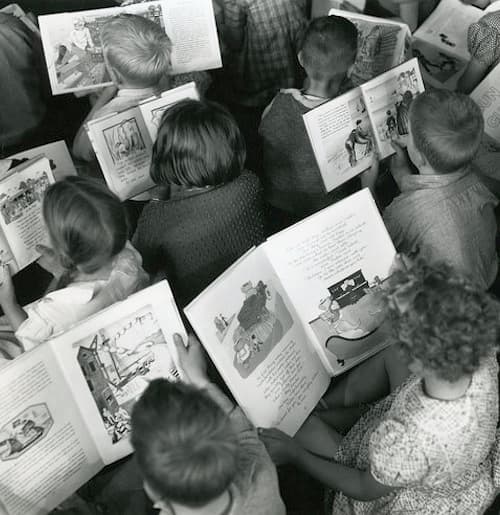

It is less the content of its curriculum, however, than the pedagogical aims of its vision statement that makes St. Jerome’s Academy so remarkable and so highly encouraging. In their Educational Plan, the authors often return to the subject of habits of attention as the foundation of their endeavor. So, classes in art, music, and biology are intended “to cultivate within the students habits and powers of looking, seeing, and noticing,” which “in turn, imply a capacity for concentration, whole-hearted attention, silence, and stillness of both body and soul.” Students will sketch in order to be trained “to attend closely to detail.” They will be prompted to listen in their music class for the same reason, because “the study of music should be to the sense of hearing what the study of art is to the sense of sight.” Even their physical education classes—in such humble, everyday sports as baseball and soccer—are understood to be for the sake of “concentration, self-discipline, and mental stamina.” The memorization of poems and speeches is another way of developing the “capacity for sustained attention,” as is the simple but time-honored practice of learning to “sit still” and to “carefully observe” a work of art. How like the sage’s observation from of old: “the possession of understanding and knowledge is produced by the soul’s settling down out of the restlessness natural to it” (Aristotle, Physics 7.3.247b18-20).

One should not, however, get the impression that mere passivity is the goal of the St. Jerome curriculum. All of this receptivity is harnessed to creative activity and plenty of it. Over their nine years in the program, the children will be asked to identify plants, to perform Shakespeare, to dance in squares and lines and to sing Latin chants, to argue, to solve problems, to sketch and to write, and, above all, to pray. It is an adventure in knowing and doing that the students are invited to join, because we are born to learn and to love what we know, and all these disciplines and activities are unto that high end. “Education,” write the St. Jerome teachers, “develops what is most human in students: the capacity for wisdom and love which requires insightful reading, depth of thought, and the autonomy that comes from virtuous self-command. These, in turn, require disciplined habits of patience, attentiveness, memory, and concentration, and a desire for what is truly good and beautiful.”

In the face of so much inanity, despair, posturing and waste in the world of education at large, it is indeed a consolation to see such a realistic and even earthy statement of curricular aims and pedagogical practices. Schools built upon models such as these are not inexpensive—although there is ample help for the sons and daughters of the less wealthy at St. Jerome’s—for the kind of care necessary to instill these good habits and encourage the attainment of these high ends always requires great labor from many laborers. A charge of elitism, then, may be expected by those who put forward plans such as St. Jerome’s. It may be asked, however, whether as a society we should tolerate the growing gulf between those few who are able to attend to arguments and to the differences that reveal the natures of things and the many who are prey to the tyranny of a digital distraction disorder. However expensive or quixotic it may seem to some, the educational ideal promoted by the St. Jerome Academy could one day soon be recognized as nothing less than a matter of the life and death of our souls.